"The Iran Nuclear Deal and the North Korean Nuclear Issue"

Russian policymakers, academics, and pundits who believe that the Iran deal was good and Russia stands to benefit from it recommend that this multilateral bargaining experience be replicated in disabling Pyongyang’s nuclear program. Those who regard it as the Kremlin’s defeat and fear Russia’s subsequent geopolitical and economic losses urge caution and raise red flags, explaining why a similar solution would not work in North Korea. Yet, both sides of the spectrum agree on, at least, three lessons. First, sanctions will not work, and international isolation will not help to resolve sensitive international security problems—be it Iran, Ukraine, or North Korea. As Alexei Arbatov says: “Applying only rude pressure on countries may be counterproductive…This overt pressure provoked a counter-reaction from Iran,”1 as it did from the DPRK.

Second, dialogue and mutual compromises are the only viable ways to resolve the international challenges posed by nuclear wannabe states. Russia will continue to stress that all problems between the United States and North Korea—that is the primary lens through which Moscow regards the North Korean nuclear issue—must be resolved using only political and diplomatic tools, including the resumption of the Six-Party Talks. As Alexei Arbatov reminds us: “The (Iranian) agreement is a compromise, as can only be expected from a document that resulted from twelve years of talks in various formats that have continued against the backdrop of Iran’s consistent efforts to pursue its nuclear program and dramatic international events.”2

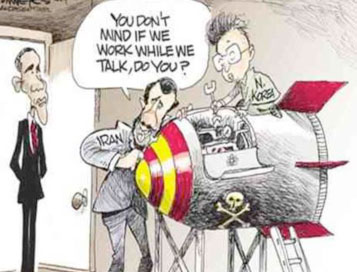

Source: Irán y Corea del Norte, ¿Nuevo eje del mal para el mundo civilizado?, http://cazasyhelicopteros.blogspot.com/2012_04_17_archive.html

Source: Irán y Corea del Norte, ¿Nuevo eje del mal para el mundo civilizado?, http://cazasyhelicopteros.blogspot.com/2012_04_17_archive.html

Third, patience and gradualism are prerequisites of success. As the Iranian nuclear negotiations demonstrate, it can take over a decade to negotiate a mutually acceptable deal, and, in Arbatov’s words, “a gradualist approach is the most realistic option for solving the nuclear issue.”3 For Russia, quietly managing the risks by silently agreeing to temporary preservation of the status quo is preferable to political destabilization and state collapse in North Korea, as long as the Kim Jong-un regime does not engage in highly provocative behavior such as proliferation of nuclear technology and fissile materials. Russian experts believe that imposing a binding nuclear test ban and capping the North’s nuclear arsenal at its current size and condition are feasible, but these can be achieved only through the diplomatic process; while the goal of actual denuclearization should be moved “over the horizon,” when relations between the DPRK and the world have improved and the need for a “nuclear deterrent” for Pyongyang might disappear.4

Help Wanted – No Iranian Experts Need Apply

Most Russian experts believe that the basic contours of the Iranian nuclear deal making may have only limited applicability to the North Korean situation. Although there may be some similarities and even pockets of cooperation between the Iranian and North Korean nuclear efforts, the differences in the role of these two countries in the international system as well as in the evolution and current status of their nuclear programs are overwhelming and limit the practical utility of the Iranian solutions for the North Korean case. Russian observers recognize the fundamental fact that, regardless of its previous international obligations, the DPRK is now a self-declared nuclear weapons state publicly intent on beefing up its nuclear arms arsenal and officially not interested in nuclear disarmament, whereas Iran claims to pursue its nuclear program only for civilian peaceful purposes within the framework of the non-proliferation treaty.

In terms of military security or economic benefits or even overall sanctions relief, North Korea has little to gain from a nuclear compromise. Despite their sharp disagreements in the Middle East, the United States does not pose an existential military threat to the security and survival of the theocratic regime in Tehran, which opened some diplomatic space for the peaceful resolution of the nuclear dispute. In contrast, any nuclear deal between Washington and Pyongyang is unlikely to remove US troops from the South or lead to the dismantlement of the alliance with the Republic of Korea (ROK), which is aimed at defeating and destroying the DPRK and reunifying the Korean Peninsula under the auspices of the South. Since Pyongyang regards those as the integral elements of the so-called US “hostile policy” against it, their continued existence precludes any reduction in the perceived US-ROK military threat and any substantial security gains for the DPRK, thereby rendering meaningless its nuclear disarmament from the security standpoint.

From the economic perspective, North Korea has very few incentives to want a nuclear deal at this time. In contrast to Iran, Pyongyang has no comparable frozen financial assets to be released; it has no proverbial USD 100 billion in foreign bank accounts. Unlike Iran, North Korea does not have crude oil and gas to ship to its neighbors; nor does it expect to be able to generate substantial new revenues on its own, once its access to global markets is reopened. The DPRK’s exports of mineral resources (mostly iron ore and coal) are already at their historical highs and are pushing the limits of the country’s industrial capacity. They go mostly to China, and they are not affected by sanctions in any significant way. The DPRK is unlikely to earn substantially more revenue without new investments in infrastructure even if other export markets are opened to it. Unlike Iran, North Korea cannot expect to be able to purchase any new weapons from the world markets because it will remain under international arms trade embargoes; nor does it have the foreign exchange to pay for them.

Lastly, Russian experts recognize that most of the international sanctions imposed on Pyongyang have nothing to do with its nuclear program; the international community imposed them to stop the DPRK’s ballistic missile program, its sponsorship of international terrorism, and for bilateral reasons (abductions of Japanese citizens, sinking of the Cheonan, human rights abuses, etc.). Even if a nuclear deal is reached, most bilateral and even international sanctions are likely to remain in place, unless a comprehensive solution covering all the issues of contention is found—which is very difficult and unlikely.

Russia’s Dubious Stance

The Iranian nuclear deal offers plenty of ground for Russian advocates and critics to extrapolate their thinking to the North Korean situation, leaving international observers confused as to whether Russia is really interested in resolving the North Korean nuclear problem at this time. Those who advocate a new nuclear deal with Pyongyang argue that it might help restore the Kremlin’s international image, increase Moscow’s leverage in bargaining with the United States, induce Western cooperation in other issue-areas important to Russia, and potentially eliminate the long-standing irritant in Moscow’s relations with Washington that is US deployment of missile defenses in Northeast Asia. According to Theodore Karasik, Russia pushed for a nuclear deal with Iran because it elevated Moscow’s status as a negotiator in the international arena. Success in the Iranian negotiations would help Russia in the regulation of the conflict in Syria, where Moscow has much higher stakes and is playing an active role in search of conflict resolution.5 “Russia’s biggest victory in the deal is one of prestige,” said Sergei Seregichev. “Who made Iran agree with the United States? It was Russia. Without Russia, there would have been no deal.”6 In the same vein, these experts argue that Moscow can reap similar reputational benefits if the international community were to settle its nuclear dispute with Pyongyang.

More cynical analysts regard Russian cooperation in the settlement of the North Korean nuclear program not just as a goodwill gesture, but as a possible bargaining chip in relations with the United States, hoping that Moscow’s “concessions” on North Korea might be able to encourage Washington to recognize Russia’s reunification with Crimea. But similar hopes with respect to Russian cooperation on Iran proved to be wishful thinking and produced no desirable effect.

Some Russian officials maintain that during the period of deepening US-Russian stand-off over Ukraine, the “North Korean issue” remains one of the few areas of continuing bilateral cooperation, which allows the Kremlin to maintain the veneer that Moscow and Washington can still work together on some issues of international security and produce some positive results. But a similar logic with respect to Iran did not block further deterioration of the overall US-Russian relationship in the past year.

Proponents of the nuclear deal with Pyongyang argue that it might help either dissuade the United States from deploying its missile defense system in Northeast Asia or force it to reveal its true intentions, namely that its missile shield is aimed against Russia and China, not the DPRK. However, the US decision to expand its missile defense assets in Europe even after the disablement of the Iranian nuclear program leaves little doubt in Moscow that Washington is likely to pursue a similar course of action in Northeast Asia, too. Those who caution against pushing Pyongyang to the bargaining table argue that, as in the Iranian case, Russia stands to gain little and lose much more from a possible nuclear deal between the DPRK and the United States.

First, in a flashback to the old Cold War-type mentality, they contend that as long as the Russian-US confrontation over the Ukraine and Europe continues, Russia needs a North Korea friendly to Moscow and hostile to Washington to protect the Russian Far Eastern flank. It is useful to have a 1.2 million man army that hates America and points its guns at 28,500 US troops in South Korea to divert US attention from Russia’s western flank, to increase its defense burden, and to dampen US willingness to extend its security commitments to Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova.

Second, bearing in mind Gorbachev’s nuclear disarmament deals with the West, they fear that the nuclear disarmament of North Korea might lead to the collapse of the DPRK state and abrupt reunification of the Korean Peninsula under the umbrella of the South, a staunch US ally pursuing policies often antagonistic to Russian national interests. Last year, Seoul joined the US-led international community in condemning Russian “annexation” of Crimea and silently supported Western sanctions against Russia; in a personal snub to President Putin, ROK President Park refused to visit Russia twice—to attend the Victory Day parade in Moscow in May 2015 and the opening or closing ceremony of the Sochi Winter Olympic Games in February 2014 (although Pyeongchang is the next host, it is customary for the head of state of the next Olympic Games host to participate in the official ceremonies organized by the current host).

Third, Russia stands to gain little from the removal of international economic sanctions from North Korea. Bilateral trade and investment are restricted by factors internal to the two countries, not by international sanctions or embargoes. That said, Moscow is unlikely to suffer economic losses comparable to those expected in the event economic sanctions are lifted off Iran.

• Once Iran’s sanctions are removed, Russia could likely be first in line to compete for lucrative contracts in key sectors such as energy, transport, and arms procurement. Iran will need foreign companies to come and invest in the development of the sectors that struggled under the sanctions, according to Andrei Baklitsky.7 Russian companies, such as Russian Railways, Lukoil, Rosatom, and Rosoboronexport are eager to return to Iran as soon as international restrictions are eliminated. But they will have to compete against major Western companies eyeing reentry into the Iranian markets.

• Besides, Russia’s prospective gains may be overshadowed by Iran’s return to the global energy market, which analysts said could drive down oil prices and squeeze Russia in supplying Europe. “Iran is very eager to export oil to Europe again,” said Semyon Bagdasarov. “An important player will be coming back on the market and competition will increase.”8 The sharp drop in oil prices between June 2014 and January 2015 was one of the major factors for Russia’s recession and cranked up pressures on state coffers.

Fourth, what is more important in the eyes of Russian nationalist hardliners is the fact that Russia may lose North Korea, just as it is losing Iran after the conclusion of the Iranian nuclear deal. According to Vladimir Akhmedov, Moscow seriously fears that the rapprochement between Tehran and Washington in the wake of the nuclear deal may lead to strategic reorientation in Iran from “pro-Russian” to a “pro-Western,” as happened with Pakistan in the 1970s. “If sanctions are lifted from Iran, Russia will be faced with a struggle for competition with Western companies, and Iran will acquire more room for maneuver,” according to Fyodor Lukyanov.9 In this regard, if the DPRK-US relations are normalized in the wake of a new nuclear deal, these people are concerned that Pyongyang might be tempted to switch sides and begin to pursue more pro-American policies, just as Burma, Vietnam and the Ukraine did. According to Georgy Mirsky, from Moscow’s standpoint, a “nuclear Iran” might be better than a “pro-American Iran.” In the same vein, as the second Cold War between Moscow and Washington settles in, a “nuclear North Korea” might be better for Russia than a “pro-American North Korea” or North Korea absorbed into the “American orbit” or into the “pro-American South.”10

Washington Holds the Key

Despite their anti-American bent, Russian observers all agree that even if some important players with the most at stake are strongly opposed to a negotiated solution (like Israel and Saudi Arabia in the case of Iran), if the United States as the sole superpower decides to make it happen, it can be done. In this regard, Washington can override Seoul and Tokyo’s objections to make a deal with Pyongyang, if it sincerely wants to do so. In their opinion, as loyal and disciplined allies, South Korea and Japan are likely to bandwagon any nuclear deal that the United States may decide to strike with North Korea. That said, in general, most Russian experts believe that the United States is not really interested in any deal-making with the DPRK at present, largely for two reasons. On the one hand, the past experience of botched agreements destroyed all the meager trust that existed between the two countries and left a very bad taste in the mouth of Washington’s policymakers. On the other, they understand that President Obama has too little time left in office to try to engage Kim Jong-un in any serious way. Besides, he has established his foreign policy legacy by eliminating Osama Bin Laden, accomplishing a historical normalization of relations with Cuba, and reaching a landmark nuclear deal with Iran. He is not going to pick yet another fight with the Republican Congress to push the North Korean deal through.

Russian observers agree that the ill-fated 1994 Agreed Framework may foreshadow the future of the Iranian nuclear deal. US domestic politics matter a lot in determining the ultimate fate of any deal with a rogue state, and they do not bode well for the long-term viability of the Iranian deal, short of regime change in Tehran. Opposition of the Republican-dominated Congress to the nuclear deal that the Clinton administration signed with the DPRK in 1994 scuttled its implementation. Even if the US Congress does not nullify the agreement with Iran within 60 days of its conclusion, it remains to be seen whether Washington will faithfully implement it.

Most Russian experts believe that Iran is likely to hedge by preserving some capacity to rebuild its nuclear potential ten years from now in case the deal falls through. In their judgment, parties opposed to reconciliation may use Iran’s hedging behavior as an excuse to justify jettisoning the deal, as happened with the Agreed Framework nearly ten years after its conclusion.

Finally, the North Korean experience taught Russian observers that if the deal collapses, one can expect a rapid nuclear breakout by Iran, as in the case of the DPRK. Even if subsequently the parties were to return to the talks intermittently, the possibility of a mutually acceptable negotiated settlement would be very slim at that point. A failure of the deal, according to Alexei Arbatov, “would make the new war in the Persian Gulf inevitable, with dire implications for international security and the nonproliferation regime.”

1. Alexei Arbatov, “What does Iran get in exchange for the bomb?” Carnegie Moscow Center, July 20, 2015, http://carnegie.ru/eurasiaoutlook/?fa=60766.

2. Alexei Arbatov, “What does Iran get in exchange for the bomb?”

3. Alexei Arbatov, “Reckless: Don’t ‘Go for Broke’ in Iran Nuclear Talks,” The National Interest, March 9, 2015, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/reckless-dont-go-broke-iran-nuclear-talks-12382.

4. Georgy Toloraya, “Russia and the North Korean Knot,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 16-2-10, April 19, 2010, http://www.japanfocus.org/-georgy-toloraya/3345/article.html.

5. Darya Lyubinskaya, “Press Digest: Nuclear Deal with Iran Could See Russia Lose Middle East Ally,” Russia Beyond the Headlines, April 2, 2015, http://rbth.com/international/2015/04/02/press_digest_nuclear_deal_with_iran_could_see_russia_lose_middl_44945.html.

6. “Iran Nuclear Deal a Mixed Economic Win for Russia: Analysts,” The Economic Times, July 19, 2015, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/iran-nuclear-deal-a-mixed-economic-win-for-russia-analysts/articleshow/48131376.cms.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Lyubinskaya, “Press Digest: Nuclear Deal with Iran.”

10. “Иран, который мы теряем,” April 2, 2015, http://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2015/04/01_a_6621961.shtml.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn