After 160 years of non-democratic colonial rule by the British, Hong Kong became part of China in 1997 under a mini-constitution, the Basic Law, that guaranteed a number of democratic civic values and pledged eventual universal suffrage for both the executive and the legislature. Since the handover, there have been protest movements demanding fulfillment of those pledges, led primarily by young people. At the same time, a distinct Hong Kong identity has emerged, again largely among the younger generation. Many who see themselves as Hong Kongers also explicitly add that they are “not Chinese.” There have been parallel developments across the Taiwan Strait. Taiwan also experienced colonial rule by the Japanese for fifty years after 1895, until the Chinese Nationalists (the Kuomintang or KMT) accepted the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II. The KMT took over the island and imposed one-party rule and martial law until 1987. In the late 1980s, an intense debate over Taiwan’s national identity, on which the two major political parties, the ruling KMT and the newly legalized Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), took opposing views, became an integral part of Taiwan’s struggle for democracy.

The development of a new identity in these two regions was inextricably linked to their democratization. Although culturally predominantly Chinese, both Hong Kongers and Taiwanese treasure their heritage yet long to be distinct from the communist authoritarian regime of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In fact, many living in these two regions had fled China decades earlier to escape the Chinese communist rule. The desire for democracy and a distinctive way of life differentiated both Hong Kong and Taiwan from the Chinese government and the Chinese people on the mainland and has become an important part of the identity of the younger generation in both places. Although the political systems are very different, both are experiencing a generational change. Young Hong Kongers and Taiwanese want to assert their distinctive social, economic and political identities that differ both from that of their elders and from that advocated by Beijing. Socially, they want to preserve freedom of expression. Economically, they question the need to prioritize growth over equality and fairness. Politically, they want to reform existing institutions and leaders, and reject political parties that have failed to make their societies more equitable and sustainable. Young people in both regions are now running for office, leading civic organizations to monitor political parties and leaders and generally becoming more engaged as citizens.

To understand how the emergence of a separate identity is an integral part of the pursuit of democracy and how pressure from China has fueled its rise requires a conceptual framework that explains how ethnic Chinese are building separate civic and cultural identities with a focus on democratic values and institutions, which they describe as an alternative to those they see in a rising China. Given the long shadow of China across Asia today, the cases of Taiwan and Hong Kong, despite their unique characteristics in nationality and culture, are instructive for others reacting to China.

Measurement of identity

In both regions, identity has been primarily defined and measured in two ways. The first is self-identification: whether one chooses to identity oneself as “Chinese” or to adopt an alternative local identity. The second is one’s preferences regarding their region’s political system and status, in particular, the level of support for One Country Two Systems (OCTS) or greater autonomy in Hong Kong and for unification or independence for Taiwan. These two dimensions of identity have been measured through public opinion polls in both regions for many years.

Hong Kong identity

Under British colonial rule from 1846 to 1997, both the British and Chinese governments avoided mobilizing a strong Chinese identity in order to minimize anti-colonial movements and maintain stability in Hong Kong. Instead, there developed a sense of local identity that was rooted more in social and economic factors than in political institutions. Residents viewed Hong Kong society as freer and more developed than China.1 They also treasured Hong Kong’s rule of law with an independent judiciary, which stood in contrast with a far more arbitrary system of governance on the mainland.

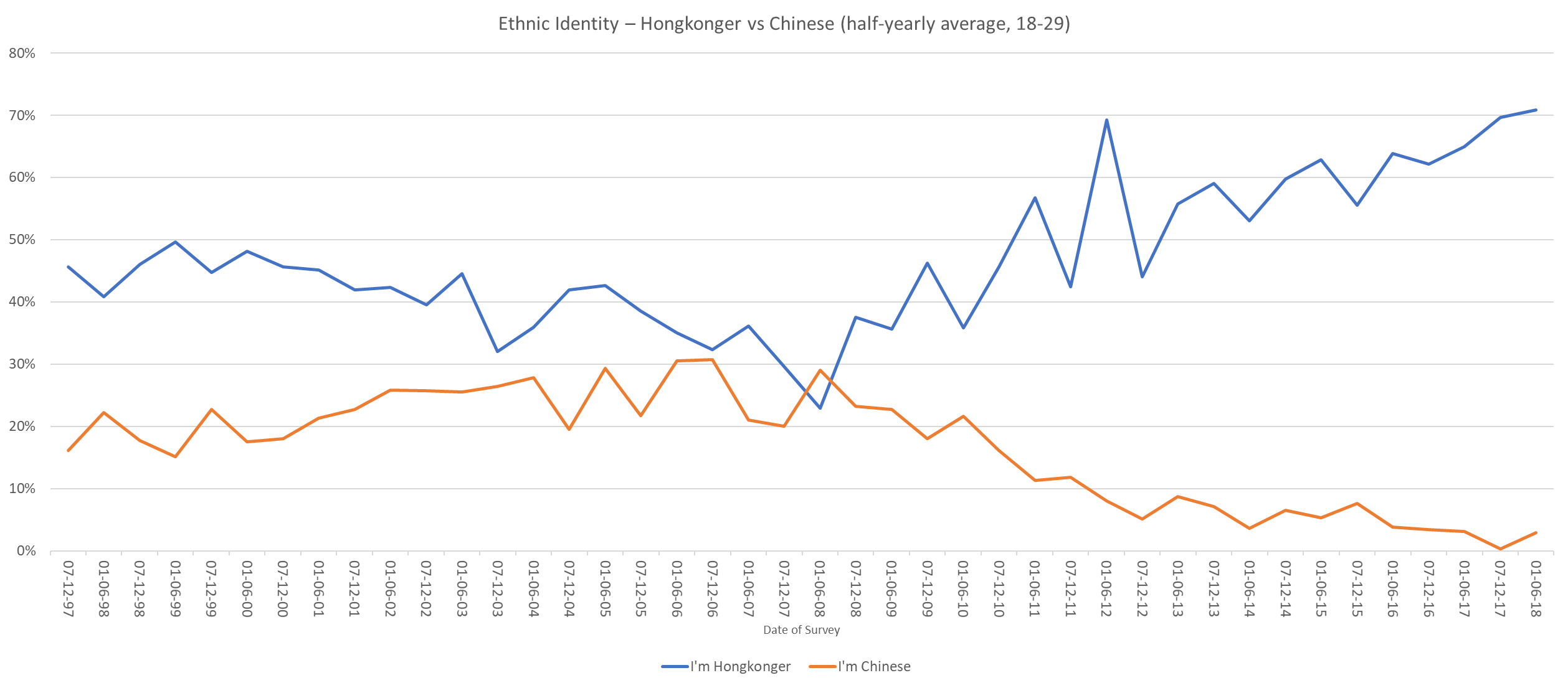

The return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty in 1997 did not reverse these trends toward a distinctive local identity. In June 2018, more than twenty years after the handover to Beijing, a survey found that 67.7 percent saw themselves as having primarily a Hong Kong identity, either a “Hong Konger in China” (26.8 percent) or simply a “Hong Konger” (40.7 percent). This was an increase from 59.7 percent in 1997. Only 29.9 percent saw themselves as having primarily a Chinese identity, either a “Chinese in Hong Kong” or a “Chinese,” a decline from 38.7 percent in 1997. More alarmingly, despite years of “patriotic education,” 96.4 percent of people under 29 years old identified themselves as having primarily a Hong Kong identity. Only 3.6 percent of the young people identified themselves as primarily Chinese, a stark contrast to the 31.6 percent recorded in 1997 (Figure 1).2

FIGURE 1 Hong Kong Identity vs. Chinese Identity for Young People, 1997-2018

Source: Hong Kong University Public Opinion Programme, The University of Hong Kong (POP), “People’s Ethnic Identity,” June 19, 2018.

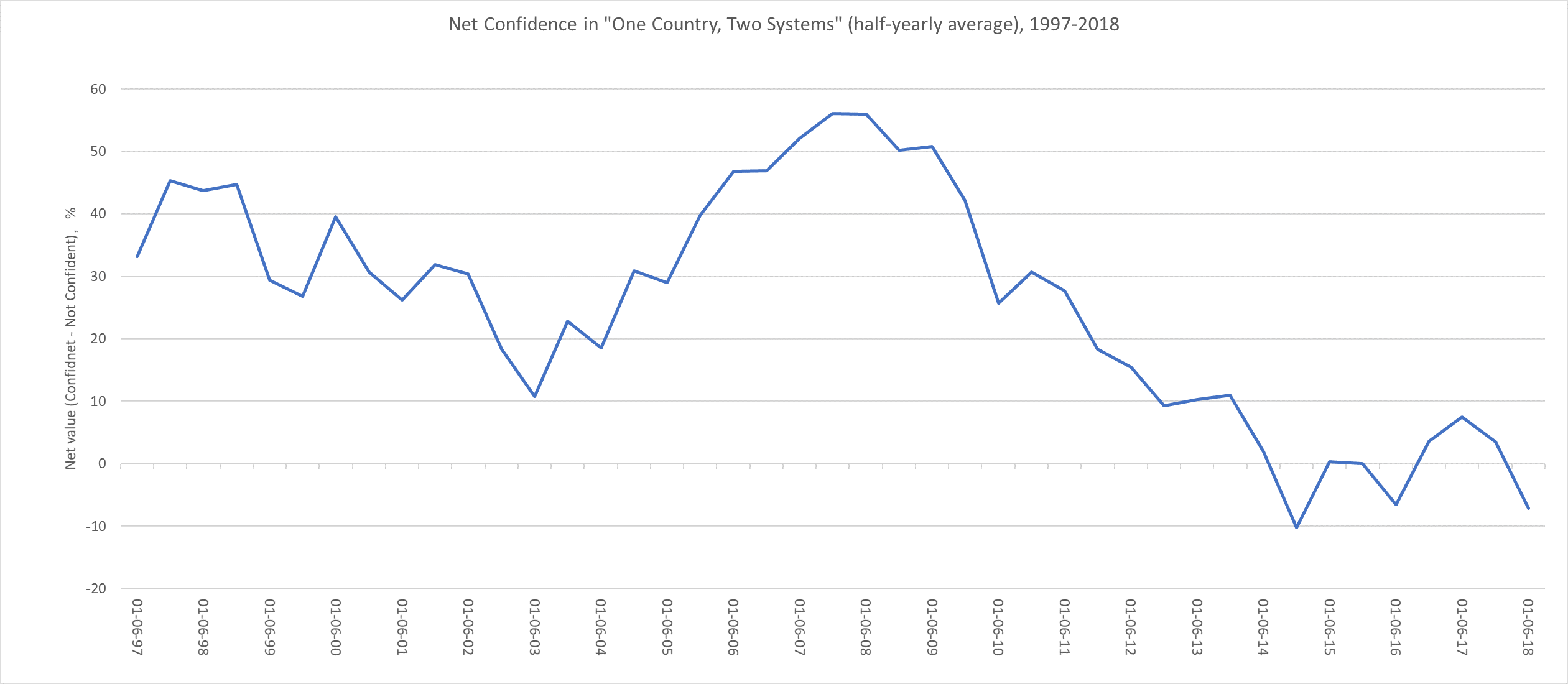

The second measure of identity used here is the degree of confidence that Hong Kong people have in OCTS, tantamount to their level of support for that system. In July 1997, the percentage who felt confident about their political system exceeded 63.6 percent but has since dropped to 45.5 percent. Conversely, those who lacked confidence in the system had risen from 18.1 percent to 49.0 percent. The difference between these two values is a measure of net confidence in OCTS and has generally been negative since 2014 (Figure 2).3 The degree of confidence is primarily dependent on whether people believe Hong Kong enjoys autonomy, free of Beijing’s interference and irrespective of changes in Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership. This is tied to perceptions of whether Beijing will allow universal suffrage as provided for in Hong Kong’s Basic Law.4

FIGURE 2 Net Confidence in “One Country Two Systems,” 1997-2018

Source: Hong Kong University Public Opinion Programme, The University of Hong Kong (POP), “People’s Confidence in ‘One Country, Two Systems’,” September 18, 2018.

Source: Hong Kong University Public Opinion Programme, The University of Hong Kong (POP), “People’s Confidence in ‘One Country, Two Systems’,” September 18, 2018.

The data further revealed that since the 1997 handover, Hong Kong identity has been contested and volatile, whether measured by self-identification or confidence in OCTS. From 1997 to 2008, there was an overall uptick toward becoming more Chinese, peaking during the Olympic Games in Beijing in 2008, and a decline in Hong Kong identity. After 2008, however, Chinese identity began to decline, and Hong Kong identity began to rise until now. Net confidence in OCTS was similarly volatile. There were several peaks in confidence level that coincided with important events such as the handover in 1997 and the Beijing Olympics in 2008. The troughs are also linked to crises in governance such as the spread of the SARS pandemic and government efforts to implement Article 23—the national security law—in 2003-2004, and the 2014 Umbrella Movement against the government’s proposal for limited electoral reforms. However, no matter which measure of identity is examined, the unmistakable and consolidating trend is a rapidly consolidating Hong Kong identity among the younger generation.

Taiwanese national identity

The open contestation over Taiwanese identity for three decades after democratization has also led to a consolidated identity that is more Taiwanese than Chinese. During the Cold War, after fifty years of Japanese colonial rule, the KMT attempted to impose a Chinese identity on Taiwanese in order to uphold its authoritarian rule and gain support for its ultimate goal of national reunification. Because of the KMT policy to distinguish mainlanders who arrived from China after WWII from local Taiwanese whose ancestors had immigrated to Taiwan earlier, an ethnic definition of identity became linked to discriminatory policies that privileged “mainlanders” over “Taiwanese.” After the lifting of martial law in 1987 when free discussion of these issues became possible, and as Beijing secured more diplomatic relations and membership in all major international institutions at the expense of the Republic of China, residents of Taiwan began a long debate over their national identity.5 Increasing criticism of the KMT-imposed Chinese identity and growing support for a more Taiwanese identity were reflected in the DPP government’s attempt to revise school curricula to be more Taiwan-centric. At the same time, the earlier primordial definition of that identity gave way to a “new Taiwanese” identity, defined less in terms of ethnicity and more as a commitment to the interests of the people of Taiwan and the island’s new civic values and institutions. National identity began to consolidate only after an intense period of contestation after new democratic institutions were established.

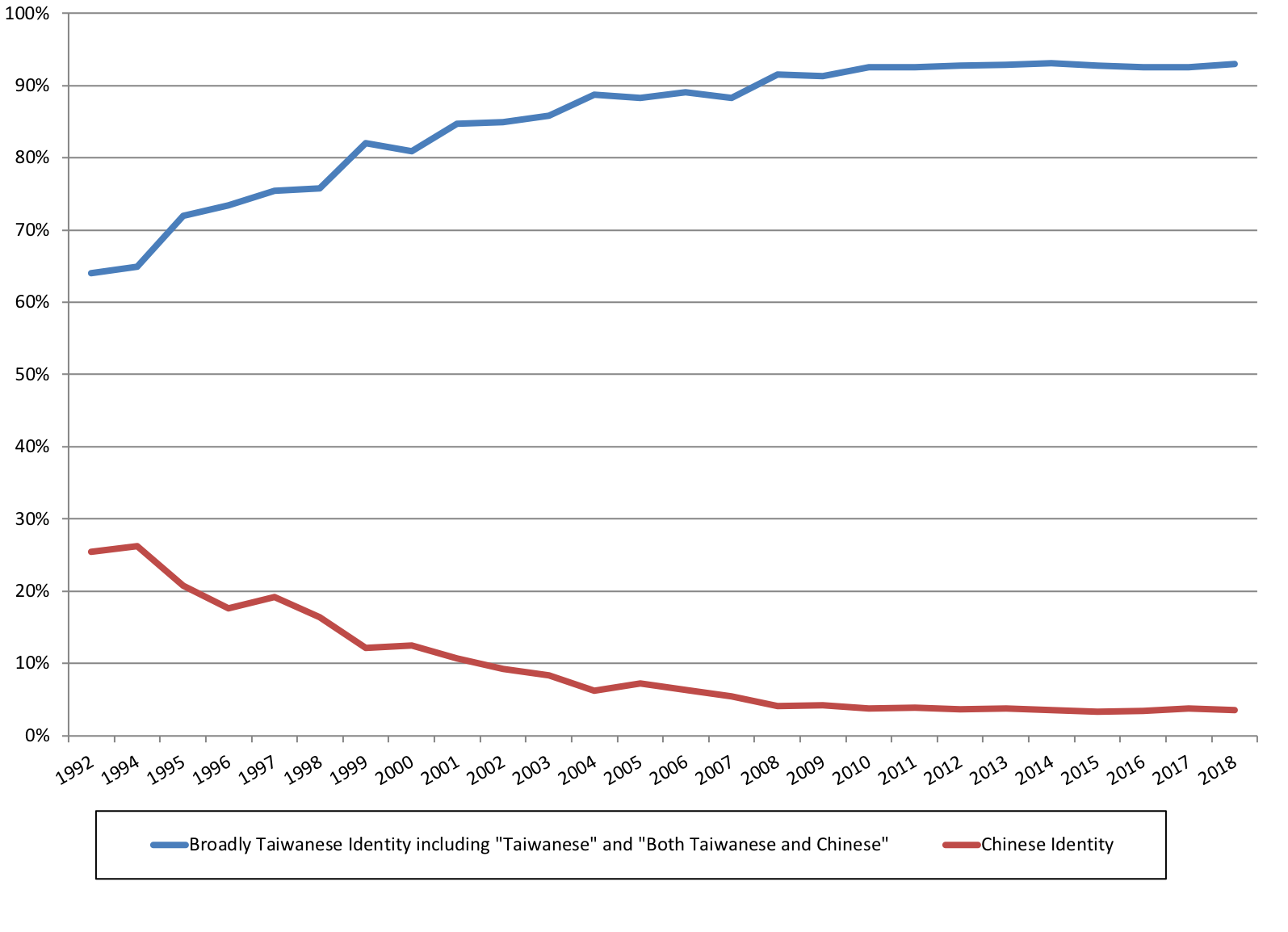

In a June 2018 poll conducted by the Election Study Center of Taiwan’s National Chengchi University (ESC), fully 93 percent of Taiwanese identified themselves as “Taiwanese” or “both Taiwanese and Chinese.” The exclusively “Taiwanese” category had increased more dramatically than the dual identity, rising from 17.6 percent in 1992 to 55.8 percent in 2018. Only 3.5 percent identified themselves as “Chinese” in 2018, a decline from 25.5 percent in 1992 (Figure 3).6 In only two decades, despite greater economic interdependence with China, the majority of Taiwanese have accepted a Taiwanese identity, moving away from a full or partial Chinese identity.7

FIGURE 3 Taiwanese Identity by Self-Identification (1992-2018)

Source: Compiled by author according to data from Election Study Center, National Chengchi University, “Important Political Attitude Trend Distribution,” August 2, 2018.

Source: Compiled by author according to data from Election Study Center, National Chengchi University, “Important Political Attitude Trend Distribution,” August 2, 2018.

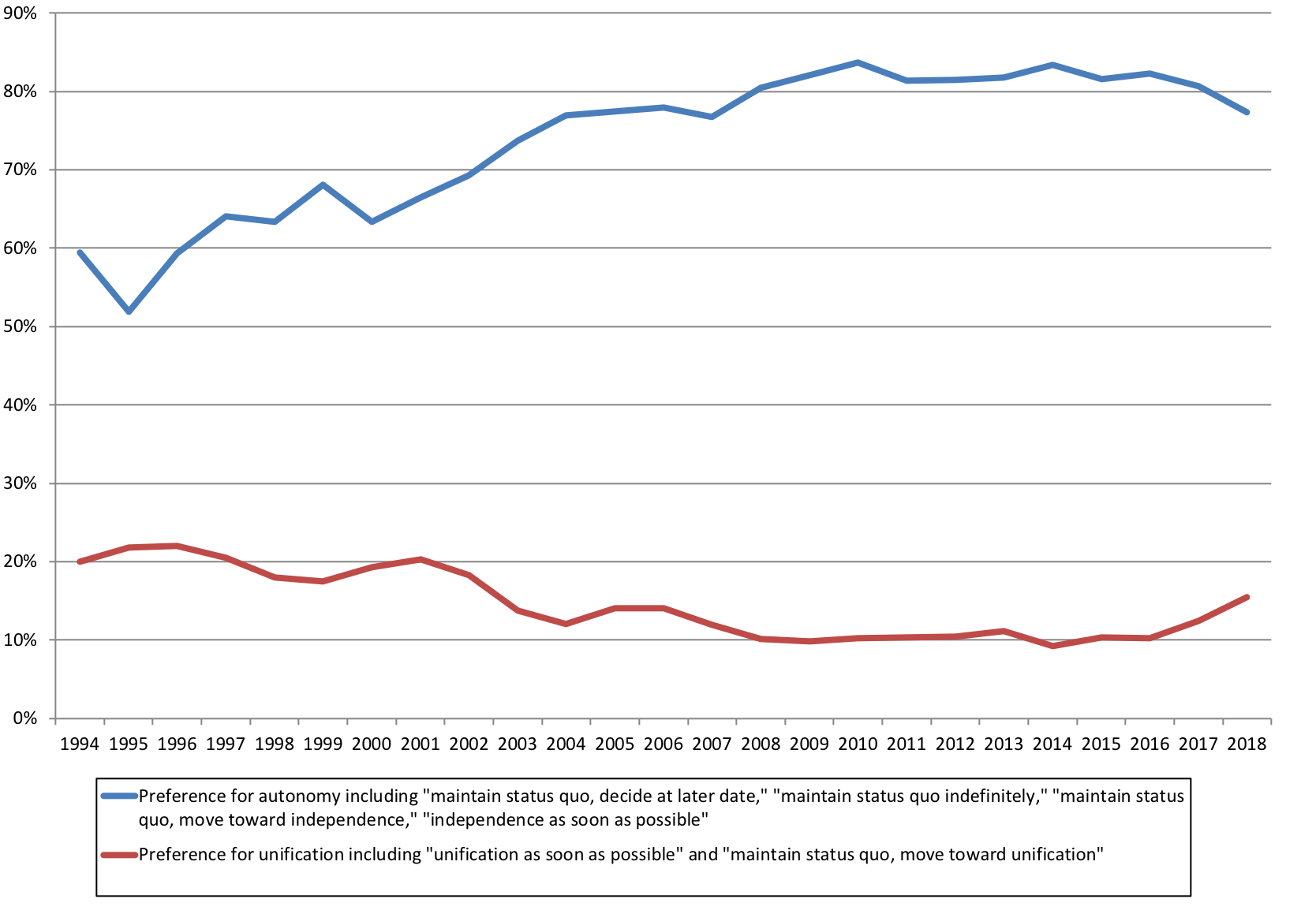

In terms of preference for unification or independence (known as future national status, or FNS), polls showed that support for immediate unification has dwindled to one to three percent over the last two decades.8 Support for autonomy, either the status quo or immediate or eventual independence, has increased from 59.4 percent in 1994 to reach over 80 percent since 2008 (Figure 4). In terms of their acceptance of OCTS, which Deng Xiaoping had said would apply to Taiwan as well as to Hong Kong, the Taiwanese were skeptical even before the Hong Kong handover and their doubts have increased given recent developments in Hong Kong. Polls in the last twenty years have repeatedly shown low support for unification, the “one China” principle, or OCTS, since most believe that any of these outcomes would curtail Taiwan’s autonomy.9 When self-identification is juxtaposed with preferences regarding FNS, it is clear that national identity on Taiwan is evolving rapidly in one direction: away from being “Chinese” or part of a Chinese state.

FIGURE 4 Taiwanese Identity by Future National Status Preference (1994-2018)

Source: Compiled by author according to data from Election Study Center, National Chengchi University, “Important Political Attitude Trend Distribution,” August 2, 2018.

Source: Compiled by author according to data from Election Study Center, National Chengchi University, “Important Political Attitude Trend Distribution,” August 2, 2018.

This trend is clear even when respondents are permitted to express their preference under positive hypothesized conditions, such as the democratization of the mainland or levels of per capita income on the mainland that match those on Taiwan. Academia Sinica has conducted surveys every five years to measure these conditional FNS preferences. The latest poll showed the continued decline in support for unification over two decades, even if China were to become wealthy and democratic, falling from 54.1 percent in 1995 to 28.3 percent.10

Although the increase in a local identity runs across all age groups in Taiwan, the increase has been higher in the younger generations, just as in Hong Kong. Young people do not think of China as an enemy and are open-minded about their relationship with China, but they have a firm local identity. Their attitude is not so much “anti-Chinese” but “non-Chinese” and Taiwanese.11 There are several age-specific surveys that demonstrate these trends among young Taiwanese. Duke University’s Asian Security Studies Program has been tracking self-identification by five age groups since 2002. The 2017 survey shows that the youngest cohort, aged less than under 30, had the highest percentage of respondents identifying themselves as only “Taiwanese” (71.2%) and the lowest percentage identifying as only “Chinese” (2.5%).12 The Taiwan Foundation for Democracy has also been tracking political attitude by age groups since 2011. The 2018 survey shows that the youngest generation in the survey had the highest level of support for independence and lowest level of support for immediate or eventual unification. Equally important, Taiwanese under 40 years of age have been much more optimistic about Taiwan’s democratic development than the older generations and yet more keen on cross-Strait economic exchanges. In other words, younger Taiwanese have a stronger sense of Taiwanese identity, but are also more pragmatic and supportive of expanded economic relations with China.13

Dimensions of identity and linkage to democracy

How are the two definitions of identity we encounter different? Identity is both how you view yourself, but also how others view you. Thus, identity is by and large constructed, either individually or collectively, and individuals usually have multiple identities. Individuals with a collective or national identity share a set of qualities and beliefs with other members of their community or group. Often times, this collective identity has an “Other”—another community, or even an enemy, against which one’s identity is contrasted.

The shared qualities of identity can be primordial. Ethnicity is an important part of a Chinese identity, and a large percentage of people living in Hong Kong and Taiwan have traditionally considered themselves Han Chinese. When the call for democracy was less salient, a majority of Hong Kongers and Taiwanese identified themselves as “Chinese” in self-identification surveys. However, the meaning of being “Chinese” has evolved to become less ethnic and more political, especially because Beijing has sought to control and monopolize the definition of being “Chinese” at home and abroad. As a result, more and more respondents feel that identifying as “Chinese” is associated with the People’s Republic of China. Moreover, they feel that self-identification is not about ethnicity or common language but rather the common values and preferences they embrace, such as freedom of speech and assembly, democracy, and rule of law.

This civic identity is also based on residency. Hong Kong and Taiwan are both places where emigres once viewed themselves as temporary sojourners. However, as more and more Taiwanese and Hong Kongers are native-born, people in these societies increasingly expect their public officials to consider these places as their permanent homes, share common values with other residents, and hold no other passports. In the case of Taiwan, people believe that those who call themselves Taiwanese should be citizens of the Republic of China and fulfill their responsibilities to perform military service, pay taxes, and vote in elections. In recent years, Hong Kongers have begun to debate what constitute Hong Kong values. While this contestation of values is intense and constantly challenged by Beijing, there is a widespread belief that Hong Kong values include the rule of law and free market principles, and more and more people also consider a high degree of autonomy and democracy to be important Hong Kong values. In a survey conducted by the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in October 2014, respondents were requested to rank what they considered as the most important among 11 values. The leading value for the general population was “rule of law” (22.9%) and “freedom” (20.8%), followed by “just and corruption-free” governance and “democracy.”14 Younger people, however, ranked freedom first, then democracy. Nonetheless, a full consensus on Hong Kong identity is elusive, in part because Beijing has discouraged discussions of Hong Kong identity, even branding them as “separatist.” At this stage, the debate displays an intensity and a degree of polarization similar to Taiwanese discussions of national identity in the early 1990s.

Because Hong Kongers and Taiwanese embrace freedom and democracy, they also prefer a political future which ensures those values. Identity has become intimately linked to democratic values in both places. Therefore, the second way of measuring identity—support for Hong Kong’s OCTS and a preference for Taiwanese autonomy—reflects preferences that are associated with civic values, rather than with ethnicity. As a result, there is high correlation between these two ways of measuring identity. If one considers himself exclusively Taiwanese, then usually the respondent would not support unification as soon as possible. Similarly, if a Hong Konger does not identify herself primarily as Chinese, then most likely she is not confident about OCTS.

My hypothesis is that a consolidated identity creates social cohesion and allows for an efficient and effective democratic government. Conversely, democratic institutions allow national identity to be discussed, contested and consolidated. Democracy and national identity are mutually reinforcing and, in the case of these two places, two sides of the same coin. Without a consolidated identity, social cohesion will be difficult to create and there will be a tendency toward social polarization and inconsistent economic and foreign policy.15 Social cohesion and a consolidated national identity do not mean a unified collective, but an agreement to promote inclusivity and embrace diversity in a democratic society with rule of law and protection of minority rights.

While many argue that consolidation of national identity must come before democratization, the cases of Taiwan and Hong Kong show that the two are mutually constitutive and reinforcing. As the contributions by Louis Goodman and Auriel Croissant in the prior Special Forum point out, the literature on democratization often looks at national identity as an independent variable: when fractured, it may impede the building of democratic institutions. But such literature does not explain what happens to national identity after democratization. Furthermore, there is little research on the relationship between national identity and foreign policy.16

Taiwan’s case sheds light on both these issues. Democratization had to take place first before national identity could be openly debated. The KMT’s one-party rule attempted to impose a Chinese identity, but many Taiwanese opposed it and fought for democracy. Still, a consolidated sense of identity emerged only after many decades of democratization. Forging a common identity is a bottom-up societal process that cannot fully occur until democratic institutions allow for free and open discussions of the common values a society embraces. Democracy both enables and requires open discussion of “who we are” as a community. In turn, a consolidated identity allows for an efficient and effective democratic system. As Taiwan became democratic, a Taiwanese identity developed that embodied civic and democratic values rather than ethnic identities. These developments then further strengthened Taiwan’s emerging democratic institutions.

Understanding national identity is absolutely essential in studying Taiwan’s cross-Strait policy. Taiwan was polarized in the early days of democratization, and pragmatic discussions of alternative policy options were drowned out by emotional invocations of identity.17 Extreme leaders and policy options were appealing because policy options were linked to the debate on identity. But as a consensus on identity was forged, the range of views on economic policies narrowed and moved toward the center.18 Discussions in recent election campaigns are now much more focused on the costs and benefits of specific policies rather than the candidates’ identity or background. A consolidated identity, however, is not sufficient to ensure consensus on economic or foreign policy. Moreover, identity can be vulnerable and fragile and debate over how to defend it may further divide the society.

By comparison, Hong Kong demonstrates how the lack of democratic institutions prevents discussion of an inclusive Hong Kong or the identification of common civic values. Instead, Hong Kong’s political institutions have produced discord rather than reconciliation. As was once true of Taiwan, the debate over identity has led to accusations that those promoting a local identity are simply engaged in “identity politics.” In the West, identity politics is often linked to populist movements on either the left or right. However, what really concerns Beijing about Hong Kong and Taiwan is less populist socio-economic policies, than the rejection of the definition of Chinese identity that the CCP seeks to promote and pro-China elites.

Origins of a separate identity

Beijing has emphasized that China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are all one “nation” ethnically, and thus should share a common identity. Since people in Hong Kong and Taiwan are predominantly Han Chinese, they do acknowledge their Chinese roots, but this does not translate easily into a common national identity.19 Moreover, the ability of government to impose such an identity is limited. While Beijing stresses common ethnicity, people in Hong Kong and Taiwan place at least equal weight on adherence to civic values that Beijing either rejects or does not fully implement, such as freedom of speech, the rule of law and an independent judiciary, an open market economy, a clean bureaucracy, and democratic institutions. Beijing’s repression of minorities in regions like Xinjiang and Tibet has long been alarming to Taiwanese, and increasingly, Hong Kongers.

During colonization, Hong Kong people, who were either from Hong Kong originally or more likely had recently fled from China, fought for the principle of “Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong,” in the 1960s in particular. They distinguished themselves from the British colonizers who gave them no political power and little civic participation. Many who fought for de-colonization were disappointed that after 1997, Hong Kong seemed to have fallen into a second period of colonization, this time by the CCP, which did not share the history and values of those in the former British enclave. While nominally adopting the principle of “Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong,” the CCP sought to restrict both democratization and autonomy.20

Taiwan has an even more turbulent history. From 1895 to 1945, the Taiwanese were ruled with an iron fist by the Japanese colonial government. While there were several “self-rule” democratic movements in the 1920s similar to those in Hong Kong under colonial rule, their focus was to loosen or remove the shackles of the colonizers rather than to define Taiwan’s distinctive identity.21 Many supporters of Taiwan independence today view Taiwanese history as a continuous struggle to achieve independence—from the Dutch, the Spanish, the Ming, the Ming loyalists in exile, and the Qing, even prior to the Japanese. When the Nationalists came after the end of Japanese colonial rule, they soon became regarded by some Taiwanese to be “quasi-colonizers” in that their ultimate aim was to return to mainland China rather than ruling for the benefit of those living on the island. The Nationalist regime was harsh and authoritarian for four decades. As in Hong Kong, Taiwanese longed to rule themselves during the half century of Japanese rule, but there was no common vision about the political future of Taiwan. Under Chiang Kai-shek’s brutal rule, dreams of political participation under the Nationalists were crushed and an independence movement emerged. This movement then ironically merged with the KMT’s anti-Communist goals to seek autonomy from the Communist regime in Beijing. After Taiwan democratized, the debate on what constitutes Taiwanese identity exploded and a consolidated identity emerged to replace the polarized quasi-ethnic identities that prevailed under the KMT rule. Today, Taiwanese pride themselves on considering all citizens as Taiwanese, including aborigines, local Taiwanese, mainlanders, and new immigrants from Southeast Asia and mainland China who have become Taiwanese primarily through marriage. Taiwanese identity is associated with distinctive institutional, societal, and cultural characteristics, particularly rooted in shared common democratic values.22

China as the other

A common feature of both Hong Kong and Taiwanese identities is that in each case “China” or “Chinese” are now the “Other.” Ironically, socio-economic integration with mainland China since it opened its door to trade and investment in the 1980s has led people living in these two regions to see how they are different communities despite common ethnic roots.23 But the Other in this case is not simply what one is not, it is an alternative Chinese identity pressed on them by a neighboring superpower. Beijing has always defined its core interests the preservation of Chinese sovereignty and territorial integrity and the promotion of national unification.24 In the case of Hong Kong and Taiwan, strengthening a Chinese national identity, especially among the younger generation, is therefore particularly important to Beijing. This means acceptance of increasing Chinese influence in Hong Kong under the OCTS formula and future unification with Taiwan. As soon as he assumed office, President Xi Jinping concluded one of his first “China Dream” speeches at the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) by calling for Hong Kong and Taiwanese “compatriots” to prioritize the interests of the nation,25 and to work with people on the mainland to realize “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” 26

Beijing believes that the development of a Chinese national identity is necessary to rule Hong Kong effectively and to secure the eventual unification of Taiwan with the rest of China. Moreover, a democratic Taiwan with freedom of speech and a Hong Kong with a vibrant market, the rule of law, and core civic freedoms, stand in contrast to the governance of the PRC. China is threatened not only by its inability to unify Taiwan peacefully and by the rise of localist sentiment in Hong Kong, but also by the existence of Taiwan as a democratic nation with ethnic Chinese citizens. This invalidates Beijing’s rhetoric that democracy is unsuitable for the Chinese people – unless Beijing is prepared to acknowledge that Taiwanese are no longer Chinese.

In order to bridge the increasing identity gap, Beijing has focused on deeper socio-economic integration with both regions. China no longer relies on either of them economically as much as it did during the early years of reform and opening. Yet Beijing still gives high priority to greater integration with both regions in the hope that it will strengthen the people’s embrace of a Chinese national identity. The Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) of 2003 granted Hong Kong preferential access to the Chinese market. For Taiwan, the Cross-Strait Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) of 2010 set the foundation for the two sides to liberalize trade in goods and services and investments. Moreover, by working closely with or pressuring businesses who have investments in China, Beijing has attempted to influence mainstream media and politics in both Hong Kong and Taiwan.27 These efforts are part of the CCP’s familiar United Front Strategy, whose three components are isolating and attacking the enemy, identifying and mobilizing a strong political base and winning over or at least neutralizing those in the middle of the political spectrum. These efforts have become more evident in both places in recent years.28

Tourism is also perceived to be an increasingly important engine for creating jobs and growth in both regions. Chinese tourists now constitute nearly 76% of Hong Kong’s annual 58 million inbound tourists in 2017 and at its peak, constituted 41% of Taiwan’s inbound tourists in 2015.29 However, tourism is a good example of Beijing’s ability to use economic interdependence as leverage over both Taiwan and Hong Kong. After the DPP’s landslide electoral victory in 2016, Beijing began to show its anger by restricting group visitors from China.30

In Hong Kong’s case, interdependence with the mainland is also reflected in a rising number of mainland immigrants, which many view as facilitating Beijing’s efforts to dilute Hong Kong values. In a city with only seven million population, mainland Chinese immigrants already constitute approximately a fifth of the city’s total.31 This number will continue to increase since 150 mainland Chinese are allowed to move to Hong Kong and establish permanent residency every day, and even more can move if they can find university placements or jobs. Taiwan has restricted immigration from China except for family and spousal reunions, but the number of spousal reunion applications has steadily increased.32

Beijing has also extended a wide range of benefits to Hong Kongers and Taiwanese who want to want to live or work in China. In early 2018, Beijing announced the “31 measures of preferential treatment for Taiwanese Compatriots,” which allow Taiwanese companies doing business on the mainland to participate in the “Made in China 2025” initiative, bid for infrastructure projects, and claim various tax incentives.33 In August 2018, Beijing further announced that Hong Kongers and Taiwanese can apply for Chinese “resident permits,” which entitle them to employment, participation in social insurance and housing schemes, and access to public services such as free primary and secondary education, basic medical care, and legal aid—basically the same rights enjoyed by mainland Chinese citizens.34

Contrary to Beijing’s hopes and expectations, however, the accelerated pace of social and economic integration has led not to a decline but to a rise in local identity. Young people continue to show declining support for unification, because they believe their values are different than those of the new immigrants from the mainland, the Chinese tourists who are visiting, and the Chinese whom they encounter on their own trips to the mainland or who they see in third places. While greater interaction with mainland Chinese tourists brought economic benefits to both economies, it also produced a rising local identity and increased tension between the two groups, as studies have shown in both regions.35

In recent years, the strategy of using economic benefits to appeal to Hong Kongers and Taiwanese has extended to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), under which Hong Kong can act as a financial center.36 With Taiwan’s current DPP government, Beijing continues to marginalize the island internationally, but Beijing dangles the carrot of being more benevolent if Taiwanese vote for candidates or parties favorable to China. Many Taiwanese hope that a more accommodative China would then allow Taiwan to join multilateral organizations or sign free trade agreements to address the socio-economic problems the Taiwanese economy faces.

Beyond economic carrots, Beijing under Xi’s leadership has increased its use of hard line and top-down tactics. For Hong Kong, these include introducing national education and patriotic propaganda, denying visas to those who it believes are promoting a local identity, and outlawing a pro-independence party and imposing harsh prison sentences and bans on standing for election for those engaged in protests.37 However, neither the soft nor hard strategy has been effective in bridging the identity gap, especially in Taiwan where Beijing has no direct control.38

As China flexes its muscles globally, it is trying to reduce Taiwan’s international space in order to demonstrate that Taiwan has no choice but to ultimately unify with the mainland. For example, China has persuaded five of Taiwan’s “diplomatic allies”—Taiwan’s term to describe those countries with which it has diplomatic relations—to switch recognition from Taipei to Beijing in the past two years, leaving Taipei with only 17 allies.

How Hong Kong and Taiwan respond to Beijing’s pressure

With local identities increasingly consolidated among young people, there have been unprecedented protests in both Taiwan and Hong Kong against their governments’ accommodative policies toward Beijing. The most notable have been Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement in March 2014, which opposed the ratification of an agreement on trade in services that would have promoted further economic integration with China. Soon after, in September 2014, Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement demanded that Beijing modify its formula for nominating and electing Hong Kong’s chief executive in 2017. Taiwanese students held sunflowers as a symbol of hope to effect change, while Hong Kong students held umbrellas to shield themselves from police tear gas. Both protests were led by young people, many of them students, some of whom expressed strong “anti-China” sentiments. This was despite the continuing efforts by Beijing to promote a Chinese identity among the young.39

Furthermore, the harsh economic realities for young people produced by the “high income trap” have not led them to embrace the economic incentives provided by Beijing.40 Inequality has widened in both places in the last decade, especially after the introduction of CEPA and the ECFA.41 Studies have shown that economic inequality and the lack of opportunity for young people in Hong Kong are closely linked to the increase in mainland Chinese immigration after 1997 as well as to the deeper economic integration with the mainland.42 Taiwan may be a more middle-class society by comparison, but inequality has increased there as well, and there is a widespread perception that integration with the Chinese economy has again been a major reason. While business elites have benefited from CEPA and the ECFA, professionals, the middle class, and the working class do not believe that tourism or trade has benefitted them.43 For students who are about to enter the workforce, jobs and opportunities at home appear to have been reduced because of economic and social integration.44 Unemployment is a particular problem for young people in both regions, and real wages barely increased as integration with China deepened, most likely because of lower labor costs in China. Finally, partially due to increased flows of Chinese capital as a result of financial liberalization, asset inflation continues unabated in both regions, leading to real estate becoming unaffordable for young people, who are then delaying forming families and having children.45

The leaders and governments of Taipei and Hong Kong have needed to play a nuanced two-level game between Beijing and their constituents. Successful negotiations with Beijing could be politically expedient to both governments, but they must keep a close eye on the opinions of domestic constituents despite their different political systems. Taiwanese politicians are directly accountable to the voters through an extremely competitive and democratic system. Having led the DPP to return to power in 2016 amidst popular sentiment that the Ma Ying-jeou government had become too close to China, President Tsai Ing-wen needs to ensure that the DPP will win the 2020 presidential and legislative elections. No political party or legislator on Taiwan can risk political support by promising further economic and political concessions to Beijing, even if such measures might be economically beneficial to certain party supporters.

Tsai needs to walk a tight rope between keeping a distance from China and solving the socio-economic problems associated with the high income trap. Although the voters sided with the DPP in both the mayoral elections of 2014 and the presidential and legislative elections of 2016, the DPP suffered a serious defeat in 2018 municipal elections for both mayoral and magisterial posts, where the KMT won 15 out of total 22 seats and the DPP merely kept six.46 Surveys show that about half of the voters profess no loyalty to either the KMT or the DPP and are swing voters. Most analysts attribute the defeat to the DPP’s poor governance and inability to provide a sound economic strategy. While the result is not deemed to be directly related to pro or anti-China sentiment, the DPP will be highly challenged to win the 2020 presidential election when so many important cities and counties are controlled by the KMT.

It is also during the 2018 election that Beijing’s sharp power emerged to possibly be a powerful factor challenging Taiwanese democracy. As opposed to soft power, which tries to appeal and attract, sharp power is defined as the penetration of another country’s media, academia, and policy community to polarize or disrupt.47 Although there is no hard evidence that Beijing spread fake news favorable to KMT candidates on social media, many believe the KMT’s landslide victory in Kaohsiung, which had voted for the DPP for two decades, showed signs of Beijing’s intervention.48

Beijing’s pressure in Hong Kong is far more tangible and direct. Under the Basic Law, the Hong Kong government only enjoys a “high degree of autonomy” in internal affairs, implying that Beijing retains authority on what it regards as major issues. The Basic Law also created several institutional channels for influence. The government was to be led by a non-partisan chief executive, with no accountability to the people but ultimately appointed by Beijing and highly sensitive to its preferences. Beijing has also made clear that the Hong Kong government would have no more leeway to negotiate political reforms, leading to more division in the city.

Nor is there a mechanism to aggregate different societal interests or solidify political support. Elected by a broader segment of Hong Kong than the chief executive but still rather unrepresentative of the general population, Hong Kong legislators are neither fully accountable to the public nor bound by party loyalty. They provide oversight on executive decisions but cannot present their own initiatives and are primarily effective in rejecting government proposals. In the most recent by-election in November 2018 to replace a localist legislator disqualified from office, the pro-establishment candidate won, giving pro-Beijing forces a majority in the Legislative Council. This means pan-democrats will no longer be able to veto government proposals. Furthermore, the local turnout dropped from almost 60% in 2016 to just 44% this time, which indicates that many Hong Kongers no longer view legislative elections as meaningful.49 The prospects for further reforms for the election of the next chief executive in 2022 are uncertain at best. Pro-Beijing individuals including retired officials, local businessmen, and journalists frequently describe student-led protests as a foreign-assisted effort to promote a “color revolution.”50 As in Taiwan, Beijing’s United Front strategy is now infiltrating all walks of life and is further dividing the city.51

Implications for the future of democracy and identity

Given these trends, is a common Chinese identity conceivable any longer? A Chinese identity of the sort Beijing prefers, which would accept limited autonomy in Hong Kong and promote unification with Taiwan, seems highly unlikely, given the consolidation of local identities in both places. A more plausible outcome would be the emergence of mixed identities, wherein residents increasingly see themselves as both Hong Kongers and Chinese or both Taiwanese and Chinese. Such mixed identities might emerge if the three governments adopt measures that ensure that economic integration provides more equitable benefits for all the residents of both regions, regardless of political outlook. In both regions, Beijing would need to consult with a wider range of social and political groups, not just the business sector and sympathetic political leaders.

None of this seems likely as Beijing is taking a hard stance toward both Hong Kong, suppressing rather than accommodating discontent, and Taiwan, where Beijing has refused to deal with the DPP government until it recommits to eventual reunification. Even if Beijing decides to become more conciliatory, China may find it impossible to increase the level of Chinese identity because neither carrots nor sticks have been effective thus far. More important, this paper has also shown that civic values are more important than ethnicity and material interests in creating a common Chinese identity, especially among the younger generations. China may therefore need to propose a new more inclusive identity based on common civic values and develop a formula for governance that embodies those values and guarantees even greater autonomy to Hong Kong and Taiwan. Unless China embraces the values that people in Hong Kong and Taiwan hold dear, or at least respects and tolerates them as an element in a more diverse Chinese polity, neither Taiwanese nor Hong Kongers are likely to become more “Chinese.”

People in Hong Kong and Taiwan bear responsibility as well. Democracy has already allowed Taiwanese to find their own voice and identity, but as Beijing continues to use sharp and hard power to discredit democracy and polarize Taiwanese society, Taiwanese must show that they can use their democratic institutions to make Taiwan even more inclusive and effectively address the high-income trap for the sake of younger generations. Hong Kong people do not have the same level of democracy that Taiwan enjoys, but they can create a stronger civil society, increase their political participation, and make their voices heard in their demands for a more accountable government and a more just society.

1. Eric Kit-wai Ma, Desiring Hong Kong, Consuming South China (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2001), 163-86.

2. Hong Kong University Public Opinion Programme, The University of Hong Kong (POP), “People’s Ethnic Identity,” June 19, 2018, http://hkupop.hku.hk/english/popexpress/ethnic/index.html.

3. Hong Kong University Public Opinion Programme, The University of Hong Kong (POP), “People’s Confidence in ‘One Country, Two Systems,’” September 18, 2018, http://hkupop.hku.hk/english/popexpress/trust/conocts/index.html.

4. Timothy Ka-ying Wong and Po-san Wan, “Hong Kong Citizens’ Evaluations of the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ Practice: Assessing the Role of Political Support for China,” in Hsin-huang Michael Hsiao and Cheng-yi Lin, eds., The Rise of China (London: Routledge, 2009), 270–83.

5. Alan M. Wachman, Taiwan: National Identity and Democratization (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1994).

6. Election Study Center, National Chengchi University (ESC), “Important Political Attitude Trend Distribution,” Trends in Core Political Attitudes Among Taiwanese, August 2, 2018, http://esc.nccu.edu.tw/english/modules/tinyd2/index.php?id=6.

7. Naiteh Wu, “Will Economic Integration Lead to Political Assimilation?” in Peter C. Y. Chow, ed., National Identity and Economic Interest: Taiwan’s Competing Options and Their Implications for Regional Stability (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 187-202.

8. ESC, “Important Political Attitude Trend Distribution.”

9. Chong-hai Shaw, “The ‘One-Country, Two-System’ Model and Its Applicability to Taiwan: A Study of Opinion Polls in Taiwan,” Modern China Studies, Vol. 16, No. 4 (2009), 96–122, (In Chinese).

10. Center for Survey Research, Academia Sinica, Taiwan Social Change Survey. All past surveys can be found in the Survey Research Data Archive, Academia Sinica, https://srda.sinica.edu.tw/browsingbydatatype_result.php?category=surveymethod&type=1&csid=2. Support for unification on a conditional basis was 54.1 percent in 1995, 48.2 percent in 2000, 37.5 percent in 2005, 29.6 percent in 2010, and 28.3% in 2015.

11. Thung-hong Lin, “China Impact on Government Performance: A Comparative Study of Taiwan and Hong Kong,” paper prepared for Taiwanese Sociological Association Annual Meeting at Taiwan Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan, Nov. 30, 2013, (In Chinese); Shelley Rigger 2006, “Taiwan’s Rising Rationalism: Generations, Politics and ‘Taiwan Nationalism,’” Policy Studies 26 (Washington DC: East-West Center Policy Study, 2006), 57.

12. Taiwan National Security Studies Survey 2017, Program in Asian Security Studies, Duke University, January 2018, https://sites.duke.edu/pass/data/.

13. Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, April 19, 2018, “Survey on Taiwanese Young People’s Political Attitudes,” http://www.tfd.org.tw/opencms/english/events/data/Event0682.html.

14. Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, “CUHK Releases Survey Findings on Views on Hong Kong’s Core Values,” October 30, 2014, https://www.cpr.cuhk.edu.hk/en/press_detail.php?1=1&id=1915.

15. Syaru Shirley Lin, Taiwan’s China Dilemma: Contested identities and multiple interests in Taiwan’s cross-strait economic policy (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 21-28.

16. Auriel Croissant, “Democratization, National Identity, and Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia,” The Asan Forum 6, no. 5 (2018), http://www.theasanforum.org/democratization-national-identity-and-foreign-policy-in-southeast-asia/?dat=; Louis Goodman, “Democratization in Asia: Lessons from the Americas,” The Asan Forum 6, no. 5 (2018), http://www.theasanforum.org/democratization-in-asia-lessons-from-the-americas/.

17. Syaru Shirley Lin, Taiwan’s China Dilemma, 209-10.

18. Syaru Shirley Lin, Taiwan’s China Dilemma, 214.

19. Frank C.S. Liu and Francis L.F. Lee, “Country, National, and Pan-national Identification in Taiwan and Hong Kong: Standing Together as Chinese,” Asian Survey, Vol. 53, No. 6 (Nov/Dec 2013), 1123-1134.

20. Richard C. Bush, Hong Kong in the Shadow of China: Living with the Leviathan (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution, 2017).

21. Edward I-te Chen, “Formosan Political Movements Under Japanese Colonial Rule, 1914-1937,” The Journal of Asian Studies 31, no. 3 (1972), 477-497.

22. Syaru Shirley Lin, Taiwan’s China Dilemma, 31.

23. Syaru Shirley Lin, “Bridging the Chinese National Identity Gap: Alternative Identities in Hong Kong and Taiwan,” in Gilbert Rozman, ed., Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies, Asia’s Slippery Slope: Triangular Tensions, Identity Gaps, Conflicting Regionalism, and Diplomatic Impasse toward North Korea (Washington, DC: Korean Economic Institute, 2014).

24. Jisi Wang, “China’s Search for a Grand Strategy: A Rising Great Power Finds Its Way,” Foreign Affairs (Mar/Apr 2011).

25. “Xi Jinping zai shierjie quanguo renda yici huiyi bimuhui shang fabiao zhongyao jianghua, China Radio International Online, March 17, 2013, http://big5.cri.cn/gate/big5/gb.cri.cn/27824/2013/03/17/5311s4055400.htm.

26. “Profile: Xi Jinping: Pursuing dream for 1.3 billion Chinese,” Xinhuanet, March 17, 2013, http://english.cri.cn/6909/2013/03/17/2941s754138.htm.

27. An example of Beijing’s effort to influence Taiwan’s elections is the “Fruit Offensive Campaign,” detailed in William J. Norris, Chinese Economic Statecraft: Commercial Actors, Grand Strategy, and State Control (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016).

28. “China Targets 10 Groups for ‘United Front,’” Taipei Times, January 15, 2018, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2018/01/15/2003685789.

29. Tourism Commission, the Government of the Hong Kong SAR, “Tourism Performance in 2017,” last modified May 16, 2018, https://www.tourism.gov.hk/english/statistics/statistics_perform.html; Tourism Bureau, Republic of China, “Visitor Statistics for December, 2015,” last modified February 15, 2016, http://admin.taiwan.net.tw/statistics/release_d_en.aspx?no=7&d=6268.

30. Tourism Bureau, Republic of China, “Visitor Statistics for December, 2017,” last modified February 23, 2018, http://admin.taiwan.net.tw/statistics/release_d_en.aspx?no=13&d=7330.

31. Mark O’Neill, “1.5 million mainland migrants change Hong Kong,” EJInsight, June 19, 2017, http://www.ejinsight.com/20170619-1-5-million-mainland-migrants-change-hong-kong/.

32. For statistics on approvals granted for mainland Chinese families to emigrate to Taiwan, see Mainland Affairs Council, Cross-Strait Economic Statistics Monthly, No. 304,August 2018, http://www.mac.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=111110&ctNode=5934&mp=3.

33. “Taiwanese given ‘equal status’ on China’s mainland, but is Beijing just trying to buy their support?” South China Morning Post, March 1, 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/2135291/taiwanese-given-equal-status-chinas-mainland-beijing.

34. “New ID card will give Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan residents same access to public services as mainland Chinese counterparts,” South China Morning Post, August 16, 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2159989/new-id-card-will-give-hong-kong-macau-and-taiwan-residents.

35. Ian Rowen, “Tourism as a Territorial Strategy: The Case of China and Taiwan,” Annals of Tourism Research 46 (2014), 62-74; Victor W.T. Zheng and Po-san Wan, “The Individual Visit Scheme: A Decade’s Review: Exploring the Course and Evolution of Integration between Hong Kong and the Mainland,” Hong Kong Institute of Asia- Pacific Studies Occasional Paper, no. 226 (2013), (In Chinese).

36. “Beijing eyes Hong Kong and London for fresh Belt and Road funds,” South China Morning Post, April 12, 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/economy/article/2141487/beijing-eyes-hong-kong-and-london-fresh-belt-and-road-funds.

37. Recent examples of visa denial include foreign journalists, see “Financial Times journalist Victor Mallet about to leave Hong Kong after visa denial,” South China Morning Post, October 12, 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2168219/financial-times-journalist-victor-mallet-about-leave-hong. The latest case of disqualification is a legislative council member who was barred from running in a village election, see “Hong Kong lawmaker Eddie Chu disqualified from running in village election after being questioned twice on independence,” South China Morning Post, December 2, 2018, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2176031/hong-kong-lawmaker-eddie-chu-disqualified-running-rural.

38. Syaru Shirley Lin, “Bridging the Chinese National Identity Gap: Alternative Identities in Hong Kong and Taiwan.”

39. Syaru Shirley Lin, “Sunflowers and Umbrellas: Government Responses to Student-led Protests in Taiwan and Hong Kong.” The Asan Forum 3, no. 6 (2015).

40. Syaru Shirley Lin, “The High Income Trap and Taiwan,” paper presented at SOAS conference on “Challenges and Opportunities of Asian Economic Integration Facing Taiwan Under the Impact of Globalization,” May 10, 2018; Syaru Shirley Lin, “Hong Kong in the High Income Trap,” FTChinese, June 29, 2017, (In Chinese), http://big5.ftchinese.com/story/001073173?archive.

41. J. Michael Cole, Convergence or Conflict in the Taiwan Strait: The illusion of peace? (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2016), 98.

42. Richard Wong, “The roots of Hong Kong’s income inequality,” South China Morning Post, March 31, 2015, https://www.scmp.com/business/global-economy/article/1752277/roots-hong-kongs-income-inequality.

43. Thung-hong Lin, “China Impacts After the ECFA: Cross-Strait Trade, Income Inequality, and Class Politics in Taiwan,” in Wen-shan Yang and Po-san Wan, eds. Facing Challenges: A Comparison of Taiwan and Hong Kong (Taipei: Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, 2013),287-325.

44. Kevin T.W. Wong and Jackson K.H. Yeh, “Perceived Income Inequality and Its Political Consequences in Hong Kong and Taiwan from 2003 to 2009,” in Wen-shan Yang and Po-san Wan, eds., Facing Challenges, 237-66.

45. “Hong Kong’s sky-high housing prices raise alarms,” Nikkei Asian Review, June 19, 2017, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Hong-Kong-s-sky-high-housing-prices-raise-alarms.

46. “Results called DPP failure, not KMT win,” Taipei Times, November 27, 2018, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2018/11/27/2003705007.

47. Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig, “The Meaning of Sharp Power: How Authoritarian States Project Influence,” Foreign Affairs, Snapshot (November 16, 2017), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2017-11-16/meaning-sharp-power; Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig, “Introduction: From ‘Soft Power’ to ‘Sharp Power’: Rising Authoritarian Influence in the Democratic World,” in “Sharp Power: Rising Authoritarian Influence,” New Forum Report, National Endowment for Democracy, December 5, 2017, https://www.ned.org/sharp-power-rising-authoritarian-influence-forum-report/.

48. “Specter of Meddling by Beijing Looms Over Taiwan’s Elections,” The New York Times, November 22, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/22/world/asia/taiwan-elections-meddling.html.

49. “Voter Turnout Rate,” Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, November 25, 2018, https://www.elections.gov.hk/legco2018kwby/eng/turnout.html?1544416670005.

50. “Occupy Central: A Color Revolution,” Ta Kung Pao, October 14, 2014, (In Chinese).

51. Sonny Shiu-Hing Lo, “China’s New United Front Work in Hong Kong: Can it Win the Hearts and Minds of Hong Kong People?” Speech delivered at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, Hong Kong, June 26, 2018, https://www.fcchk.org/event/club-lunch-chinas-new-united-front-work-in-hong-kong-can-it-win-the-hearts-and-minds-of-hong-kong-people/.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn