The biggest strategic challenge for policymakers in the Asia-Pacific is the peaceful integration of China into the international order. Within three decades, China has transformed from a rural society to the second largest economy in the world. As China continues to grow economically and its interests and influence expand, its neighboring countries and the United States will have to find a modus vivendi that fosters peaceful growth and cooperation. However, if history serves as a guide for the future, ascendance of new great powers tends to create tension, rivalry, and even war. Looking for historical analogies, some China watchers argue that with China’s rise the contours of a new cold war are beginning to take form. They see evidence for this in the arms build-up in the Asia-Pacific region, the growing rivalry over political influence, and the competing ideological and economic models that the United States and China follow and advance.

This article aims to answer the question of whether the contours of a new cold war are beginning to take shape by interpreting the Sino-US relationship based on the three mainstream international relations theories—realism, liberalism, and constructivism. Each of these theories offers different perspectives on China’s rise and the US response. If each of these theories point in the same direction, the answer will be clear. If the theories predict different paths, there will be some room for us to choose our future.

Realism: The Politics of Power

Power transition theory explains how emerging new powers challenge the hegemony of a dominant state and try to shape a systemic structure favorable to their own interests.1 It argues that ultimately a country’s potential power rests on the size of its population. For China—a country with a population more than four times the size of the United States—it means that overtaking the United States will only be a matter of time. Likelihood of war increases as “the power of a dissatisfied rising state reaches parity with a declining status quo state.”2 Structural realists add that the absence of a supranational authority makes it impossible even for the most virtuous states to escape from conflicts and security dilemmas.3 Therefore, many realist scholars in the past have argued that as China’s power will continue to grow, it is likely that it will shift towards a revisionist strategy.4

In short, according to realist theory, a combination of parity, anarchy, and dissatisfaction is a dangerous amalgam that is likely to lead to conflict and possibly escalate into full-scale war. This can be a preventive war instigated by the hegemon, trying to keep its position, or a war prompted by the challenger as soon as it perceives it can emerge victorious in a conflict with the declining power. Deng Xiaoping’s advice to China’s future leaders to “observe calmly, secure our position, cope with affairs calmly, hide our capabilities and bide our time, be good at maintaining a low profile, and never claim leadership,” seems to follow this logic. It evidently raises the question of what China should do once it feels more powerful and confident. In 1994, Denny Roy already professed that China’s transformation “from a weak, developing state to a stronger, more prosperous state should result in a more assertive foreign policy.”5 After almost two decades of increasing military spending, it seems that Chinese foreign policy has become just that. Cues for this are seen in China’s handling of its territorial and maritime disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines, India, and Japan. The question is how countries react to China’s growing military expenditure and whether a Cold War-like arms race is taking place.

An arms race?

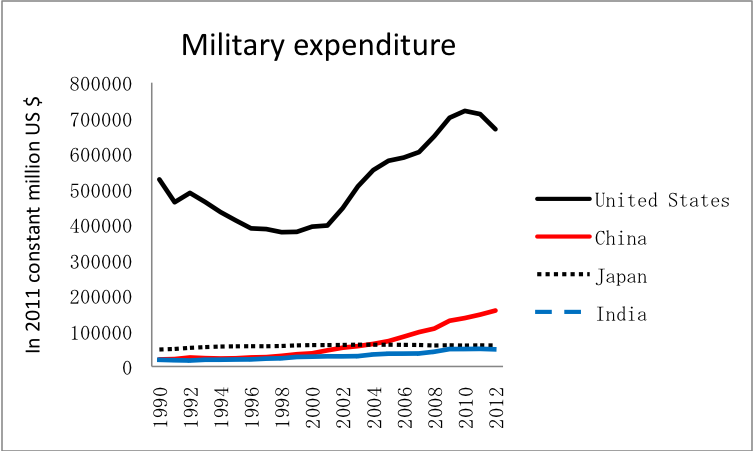

As shown clearly in Graph 1, China’s military expenditure is still minor compared to that of the United States. The increase in American defense spending from 2001 onwards came first and foremost as a result of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and, therefore, cannot be attributed to active balancing action against China’s growing power. Military spending in the United States dropped by 6 percent in 2012 with additional cuts planned for FY 2013 and 2014. The graph also shows that Japan, geographically close and strategically suspicious of China, has until recently not actively balanced against China’s growing military capabilities. Defense expenditure in Japan has actually declined by 3.6 percent in the 2003-2012 period. Finally, it should be noted that China’s rapid military modernization is partly a result of its economic growth. China’s military expenditure has been very stable at around 2.1 percent of its GDP for the last decade. Significantly lower than that of South Korea, India, and the United States, and in no way comparable to the Soviet defense spending in the Cold War era. For Beijing, the rationale for military modernization, as mentioned in the 2010 Chinese Defense White Paper, is that modern military assets are essential for protecting Chinese interests in the unification with Taiwan, securing its sea lines of communication, actively engaging in military operations other than war (MOOTW), and fighting irregular enemies (the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s first mission in distant waters was in Somalia to contribute in the anti-piracy activities). China’s military prowess is supposedly not intended to be used against any country. As Beijing stresses, China is not a military threat to any country and it will never “seek to dominate or pursue an expansionist policy.”6 This evidence all seems to suggest that a Cold War-like arms race has not yet started.

Graph 1: Military expenditure of major countries in Asia

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Military Expenditure Database,

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Military Expenditure Database,

http://www.sipri.org/research/armaments/milex/milex_database

Despite these trends and China’s rhetoric, there have been growing concerns over China’s intentions in its neighborhood, particularly in the last few years. With American involvement in the costly wars in Afghanistan and Iraq ending, the Obama administration can allocate a larger amount of resources to the Asia-Pacific region. Former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta mentioned that as part of the US pivot to Asia, it will allocate 60 percent of its naval ships to the Pacific and 40 percent to the Atlantic by 2020.

Japan’s National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) of 2010 provided for a major overhaul of its security policies, redirecting its focus towards China. Tokyo plans to increase the number of submarines and modernize Japanese fighter jets in an attempt to bolster its capacities to better deal with regional contingencies with China. Newly-elected Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also pledged to raise the military expenditure above the informal cap of 1.0 percent of GDP.

As shown in the graph, India has also been modernizing its defense forces at an increasing rate. Despite the fiscal restraints as a result of the slowdown in India’s economic growth, New Delhi is investing heavily in new naval (submarines) and air assets (including a planned US$15 billion deal with Rafale for 126 fighter jets). India is, in fact, the largest importer of conventional weapons for the period of 2008-2012, accounting for 12 percent of conventional arms imports worldwide.7 With reference to China, Ashwani Kumar, a member of the ruling Congress Party, was quoted saying that “India has consistently opposed an arms race—but India will not be found wanting in taking all measures necessary for the effective safeguarding of its territorial integrity and national interests.” 8

Other countries in the region are also planning to acquire capabilities to hedge against China’s maritime power. Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines are all looking to increase and/or modernize naval assets, in particular submarines for area denial purposes. Australia is also planning to upgrade its current submarine fleet, although fiscal constraints seem to slow down this process of renewal. In contrast to other countries in its direct surroundings, Australia’s defense budget in 2012 went down to US$25.5 billion, which is 5 percent less than its 2010 military expenditure.9

Despite this exception, it is notable that in 2013, for the first time in modern history, Asia has overtaken Europe in its defense expenditures. This is partly due to the fact that economic growth allows these countries to invest more on defense. As long as Beijing remains assertive in its foreign policy and non-transparent about its military modernization, states are likely to feel threatened by its rise and will continue to invest in capabilities to hedge against Chinese assertiveness.

Battle for influence

Since the end of the Second World War, the United States has introduced a series of bilateral security assurances with countries in the Asia Pacific. Japan, Australia, Thailand, and the Philippines, amongst others, were receptive to the deployment of US troops on their soil. The so called hub-and-spoke system provided the United States with forward deployed forces in strategic areas in the Asia-Pacific. Its continued existence is paramount to the continuation of American power projection in the region. In his address to the Australian Parliament, President Barack Obama last year mentioned that the United States would “play a larger and long-term role in shaping the Asia-Pacific region and its future, by upholding core principles and in partnership with allies and friends.”10 Obama stressed that the United States is a Pacific power, and that it is committed to upholding and strengthening international law and norms, free and fair trade, and human rights. He mentioned that the renewed American focus on the Pacific constituted a drastic shift in its foreign policy. Old wars (in Afghanistan and Iraq) were ending and the new Pacific century is dawning. The momentum is there. States in the region are more receptive to the deployment of US troops, increased bilateral cooperation with the United States, and amongst themselves than they were a couple of years earlier.

In that regard, it is not surprising that Prime Minister Abe’s first trip abroad was to Southeast Asia. Japan and the Southeast Asian countries have not only become natural allies in their shared anxiety over a rising China but have also strengthened bilateral trade and investment. Investment from Japan to Southeast Asia doubled in the last year to 1.5 trillion yen, overtaking Japan’s foreign investments to China.11 Japanese companies are keen to invest in Southeast Asia, since many cities there offer lower labor costs than is currently the case in China. Moreover, as a result of the bilateral tensions over the contested Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands, Japanese companies located in China have suffered from vandalism, theft, and lost trade. Many of those companies are now choosing to leave China.

The other element in the US hub-and-spoke system, Australia, has agreed to station 2,500 American troops in Darwin. Obama said the initiative “will mean that we are postured to better respond together, along with other partners in the Asia-Pacific, to any regional contingency, including the provision of humanitarian assistance and dealing with natural disasters.”12 The move is widely interpreted as a way to balance Chinese influence by building up forward deployed forces close to the South China Sea. Other countries in the region are also open to an American presence in their backyard. Washington seeks further cooperation with Singapore (which agreed to host four US combat ships ), the Philippines (both parties are looking to increase the American presence in Subic Bay Naval Base and Clark Air Base despite constitutional restraints), Vietnam, and Taiwan. The opening up of Myanmar has also offered opportunities for the United States to exert influence in a country recently aligned closely with China.

Cambodia is one of the few countries in the region that remains close to China. At the 2012 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit in Phnomh Penh, it contended that the ASEAN countries had agreed not to “internationalize” the South China Sea issue, much to the chagrin of the Philippines and Vietnam. The statement was withdrawn, and for the first time in ASEAN history the summit was unable to issue a joint statement. In the last few years, it has become clear that the United States is doing its best to reaffirm its commitment to the region by enhancing its traditional alliances and looking for new partnerships and cooperation. At the same time, it appears that China is increasingly isolating itself politically as a result of its own choices.

Liberalism: The Effects of Liberal Economics and Democratization

China and the United States are major trading partners, each mutually dependent on the other for economic growth and prosperity. In 2011, the largest portion of American imports (18.4%) came from China. For China, the United States is the single biggest destination for its exports (accounting for 17.1% of its outgoing trade in 2011), although overall exports to the European Union (EU) are higher.13 This economic interdependence is one of the most compelling arguments liberals make as to why a war between China and the United States is highly unlikely.14 Both countries simply have too much at stake. Moreover, when it comes to institutions and international regimes, China has proven to become socially embedded into the regional and global institutions. It has joined a host of existing regional ones, such as ASEAN+3, ASEAN+6, ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), and the East Asian Summit (EAS) as well as global institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO). It has also started the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

The web of institutions, the active involvement, and the level of interdependence in Asia are very different from the Cold War situation, in which the two opposing blocs had little economic interaction. In 1979, during the last year of détente, the United States and Soviet Union reached a peak in their bilateral trade, when 1 percent of American trade was with the Soviet Union. Meetings between heads of state only occasionally occurred in high-level summits during the Cold War. Between 1955 and 1979, there were a total of only 11 summit meetings, very few in comparison to the number of times Chinese and American leaders meet nowadays. As part of the engagement strategy, American and Chinese meetings occur on many levels and on many specific issues, some of which are politically sensitive. The meeting between Xi Jinping and Barack Obama in June 2013 took place in an informal setting and was meant to forge personal ties between the newly-reelected and elected presidents. Both parties talked about sensitive issues like cybersecurity, North Korea and industrial espionage.

It shows that the default policy of most countries in the region towards China has been—and to a large extent still is—one of engagement. This not only aims to socialize China into a liberal order, but also to transform China from within. Through trade and investment, the United States tries to promote the emergence of a powerful middle class, a potential standard bearer for political change.

It is still not clear whether China is headed toward economic and political liberalization and democratization, however. Economic development under Deng was aimed at not only improving the livelihood of its citizens but also coping with growing internal and external pressures, which would in turn help “strengthen the political legitimacy of the CCP [Chinese Communist Party].”15 Part of this development included a major reform of the economy, including accepting a market economy and open-door policies. Creation and expansion of the private arena reduced the intensity of political conflict, kept citizens apolitical, and elevated economic development to a more stable and predictable footing.16 Strategic industries were kept under state or party control, while other industries were left without state interference, or were even listed overseas. The private sector expanded rapidly. It caused many Westerners to believe China was on a one-way track to a US-style market economy.

Behind the economical and administrative reforms and the emergence of new Chinese multinationals, the CCP kept an unambiguous posture. It appointed business leaders, monitored financial executives, and shaped society through its hefty propaganda machine. In 2002, Jiang Zemin announced that entrepreneurs could officially join the Party. By incorporating the private networks in the CCP’s political structure, Jiang believed he could combine liberal economics with authoritarian politics, and combine the invisible hand of the market with the visible hand of the state. Business leaders gained more influence in Chinese politics at the expense of the ideological traditionalists. Richard McGregor identified it as the real conflict in China, in which traditionalists and the new business-leaders-turned Party members argue about the Party’s far-reaching involvement in business and economics.17

Corruption and bribery are some of the most perverse effects from the increased importance of money over ideology. Many of the new leaders of China prefer to read their bank account slips instead of old little red books. In response to these perverse effects, China’s new leader Xi Jinping repeatedly stated that he will fight corruption and increase government transparency. Also, the new Chinese government, with Premier Li Keqiang in the driver’s seat, has started talking about reform initiatives to curtail the power and influence of the state in the economy. Many experts believe that this will lead to structural adjustments in the Chinese economy. In particular, it will mean that the favorable position of the state owned enterprises (SOEs) will be heavily affected. Although it seems that the current administration in China is heading into a direction the United States would support, it is too early to tell how these reforms will turn out.

The limits of interdependence, competing economic systems, and trade frictions

There are some potential challenges to these liberalist assumptions, however. First of all, economic interdependence does not necessarily mean that countries will not go to war with each other. The period leading up to the First World War was a time of increased international monetary and economic integration and cooperation. The West European countries had high trade-to-gross domestic product ratios—35 percent for Germany and France and 44 percent for the United Kingdom.18 European countries were actively involved in bilateral trade and investment with each other. The German financing of French mining in the Longwy-Briey region is exemplary of how both nations were willing to cooperate even under growing bilateral political pressure.19 International trade grew. Production of iron and steel multiplied. New technologies like railways lowered transportation costs and increased mobility. The levels of world production as well as trade flows were unprecedented. All this led Norman Angell to believe that the European nations would not go to war anymore, because the incentive to go to war (and to destroy each other’s economic capabilities) was lost. The only way to destroy trade would be “by destroying the population, which is not practicable, and if he could destroy the population he would destroy his own market, actual or potential, which would be commercially suicidal.”20 Four years later, Europe entered the First World War.

Second, economic interdependence can also produce friction and trade wars. In the 1980s, a rising Japan came under severe American pressure to lower its tariffs and open its markets. The growing trade imbalance between the United States and China (over US$300 billion in 2012) is a major source of friction between the two countries. Washington blames Beijing for not playing by the rules of the game by keeping its currency artificially low, subsidizing exporting companies, and not protecting intellectual property rights. The Chinese and American political economies are in many respects very different from each other. In the latest report to Congress, former US Trade Representative Ron Kirk said the root problem why China, 11 years after joining, had not fully embraced WTO key principles is because of “the heavy state role in the economy.”21

Finally, the liberal argument that institutions have a pacifying effect is not necessarily true. Institutions can also become stages for competition and rivalry. As mentioned above, China has joined many regional institutions. However, China focuses mainly on Asian-centered regionalism (ASEAN+3, EAS, and SCO) in which it can play the dominant role. The United States continues to rely on its hub-and-spoke system for its military forward presence and on multilateral organizations and bilateral partnerships for its political influence, while now promoting its Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)—an ambitious free trade agreement that excludes its main trading partner, China. Both China and the United States want to play the leading role in shaping the region and use institutions and regimes to pursue those objectives.

For now, interdependence and institutionalism will continue, since this is to the benefit of all parties involved. Economic reforms in China can further improve relations with Washington. And although both countries are looking to expand their influence in the region and use institutions as a way to do so, those talk shops also serve as a way to deepen understanding of each other and avoid misperceptions. In any case, from the liberal point of view, the current situation is simply not comparable to the Cold War. Regardless of whether the liberal factors can prevent wars or not, the Sino-US relationship is by far in a better shape than the US-Soviet Cold War relationship ever was.

Constructivism: The Issue of Identity

In contrast to rationalist theories like realism and liberalism, constructivism argues that ideational factors can better explain foreign policy behavior.22 Constructivists assume that states interact with each other based on their intersubjectively constituted identities, norms, and values. Identity in this sense has been defined simply as the way a country sees itself.23 A change in identity can lead to unpredictability as other states will not be sure what kind of behavior this new identity will produce. Since the end of the Cold War, geopolitical changes have necessitated Chinese leaders to reflect on the role they want to play in the region. The CCP has to play a difficult two-level game in which it has to secure its legitimacy domestically while not unnecessarily causing concern over its foreign policy directions to its neighbors.

The Tiananmen events in 1989 made Chinese leaders aware of the fragility of their leadership. Those feelings were reinforced by the international developments when the Soviet Union imploded in 1991. As communism collapsed in Eastern Europe, and the end of ideological struggle was proclaimed in Francis Fukuyama’s influential article, “The end of history,” Chinese leaders began to question the survivability of communism.24 The long-term response to those domestic and international pressures was patriotic education.25 One way for governments to legitimize their rule is to look for historical antecedents and claim their rule as a continuation of an often revered era. According to the official history, roots of the CCP go back before Mao. The CCP asserts that “the historical inevitability of the CCP’s establishment” can be traced back to 1840.26 In the Chinese official discourse, socialism, nationalism, and party rule are closely linked. Through education and propaganda, the CCP is able to deliver this message to the Chinese people. More recently, Xi Jinping has been advocating a “Chinese Dream,” a vision of progress and prosperity for China and its citizens. But with it also comes the danger of stirring up nationalistic sentiments, which might result in adventurism in foreign policy. As stated above, one peg of the Party’s legitimacy comes from economic growth. This growth will end someday in the future, be it in 2020 or 2030. The other peg of CCP legitimacy comes from nationalism and the fact that the Party has made China great again. It is not unlikely that as economic growth slows down, the CCP, for reasons of regime survival, will further amplify these nationalist sentiments. Already, China is isolating itself as it has become more nationalistic in its tone and more assertive in its behavior.27 Such trends are worrisome for many countries in the region.

Welcoming the US pivot to the Asia-Pacific region, many countries have shifted their strategies from engagement to hedging. At the same time, it is vital that these countries look for cooperation with China to send a clear signal to its leaders and people that a prosperous and integrated China would be welcome. Engagement with China remains crucial for regional peace and stability for this reason. In a 2012 public opinion poll, the American public showed their strong support for cooperative policies towards China (69%), instead of trying to limit China’s power (28%).28 This is very different from the Cold War era, when the dominant strategy of Washington was to isolate Moscow and to contain the spread of Soviet power and ideology.

According to constructivist assumptions, a China that turns increasingly isolationist and inward-looking can only have negative consequences for regional stability and economic growth. There are some countervailing forces at work, however, that could thwart such a development. For one, with the information age in China as well (including increased access to Internet, microblogging, and social networks), one-way information dissemination is not likely to endure. The Chinese government will have to deal with a well-informed domestic audience that can find and disseminate information more freely. The number of Internet users in China grew to over 560 million by the end of 2012. Popular websites like Weibo, although censored to some extent, allow for greater freedom of speech and offer everyone with an Internet connection an opportunity to reflect on daily politics. Certainly, the Internet also offers a platform for sensationalism and agitation, and could further amplify nationalist sentiments. We must watch out for that.

At the same time, an increasing number of Chinese students are studying abroad, in particular in the United States. This is very different from the Cold War era when the Soviet Union annually sent only tens of students abroad to top universities.29 In the latest report of Open Doors, we can see that the largest group of foreign students studying at American universities nowadays is Chinese. More than 25 percent of the foreign student population in the United States comes from China, almost double the number two sender country, India.30 A Cold War case can aptly illustrate the power of intellectual exchange. In 1958, Alexander Yakovlev was one of the first batch of only four Soviet students sent abroad to study in the United States under the Lacy-Zarubin exchange agreement. He studied at Columbia University, returned to the Soviet Union, was promoted under Mikhail Gorbachev, and became known as the “godfather of glasnost.”31 What kind of effects this foreign education will have on Chinese society remains to be seen. Nonetheless, such interactions are positive signs that are likely to enhance mutual understanding and appreciation.

As mentioned above, the current CCP leadership has to take a delicate balancing act, pleasing an increasingly critical and patriotic domestic audience while trying to reassure the region that China’s rise does not constitute a threat. Ideologically, there are less fundamental differences between the United States and China than between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. China, although in a different stage of economic and political development than the United States, has shown its willingness to reform and is less ideologically rigid than the Soviet Union was in the past. Whether Beijing chooses a path of globalism or nationalism depends on how confident its leaders feel about their own position at home and China’s role in the world, and to what extent American leadership is at ease with a more influential and powerful China.

Conclusion

This article looks at the current geopolitical situation in the Asia-Pacific to see whether a Cold War scenario is transpiring. As outlined above, the three mainstream international relations theories offer different perspectives on China’s rise and the regional response.

First, realist predictions that a more powerful China will become more assertive in its foreign policy behavior are becoming more prevalent. Japan, the Philippines, and Vietnam are witnessing firsthand a change in China’s handling of what it now considers its core national interests. Diplomacy cannot curtail what countries in the regions perceive to be increasingly revisionist intentions and a fast-moving buildup of military capabilities to achieve it. We have discussed how countries in the region have legitimate security concerns and are balancing more against China’s growing power, although comparisons to an arms race or a Cold War situation are far-fetched. As long as it does not escalate into an arms race, active balancing by countries in the region can contribute to checking Chinese power, constraining adventurism, and ultimately having a pacifying effect.

Second, liberal foundations remain strong. Economic interdependence and policies to ensure peaceful and cooperative relations are still in place. China remains the number one trading partner for most of the countries in the region. Its huge consumer market and demand for resources make it an engine for economic growth in Asia. Overcoming trade frictions by cooperating on unfair trade practices is necessary to avoid turning this positive side of Sino-US relations into a negative one. When it comes to institutions, despite the growing involvement of the United States and China in regional bodies, there remains a lack of frameworks in the Asia-Pacific region to effectively deal with crisis management. This may lead to misperceptions and escalation. Since skirmishes are likely to continue, effective crisis management is all the more important to prevent confrontation.

Finally, from the constructivist perspective, we have identified positive and negative trends. As China’s power grows, so does its influence and its national interests. Although this is a rather natural development in international relations, China’s increasingly nationalistic discourse make it a source of concern as to what cost China is willing to pay to secure its national interests. One of the main variables that will affect China’s foreign policy orientation will be how its leaders will deal with the domestic pressure they face. Sharing ideas through academic, official, and youth exchange, and promoting interaction and tourism can counter such inward-looking tendencies.

In any case, a containment policy of China comparable to the Cold War is not realistic. The United States and the Soviet Union were adversaries with little interaction or interdependence. Liberal and constructivist arguments about today’s interdependence, interaction, and engagement cannot be applied to the Cold War standoff. Preconditions for a different course exist today. We will see whether we can go down that path, warding off the trends towards nationalism, assertiveness, and zero-sum competition.

1. A.F.K. Organski, World Politics (New York: Knopf, 1968); and A.F.K. Organski and Jacek Kugler, The War Ledger (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980). For a more recent application of power transition theory to Sino-US relations, see Ronald L. Tammer and Jacek Kugler, “Power Transition and China US Conflicts,” Chinese Journal of International Politics 38, no. 5 (2011); and Jack Levy, “Power Transition Theory and the Rise of China,” in China’s Ascent; Power, Security and the Future of International Politics, ed. Robert S. Ross and Zhu Feng (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2008).

2. G. John Ikenberry, “The Rise of China: Power, Institutions and the Western Order,” in China’s Ascent; Power, Security and the Future of International Politics, ed. Robert S. Ross and Zhu Feng (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2008), 93.

3. Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979).

4. For theoretical arguments, see John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: Norton, 2001); and Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983). On China, see Denny Roy, “Hegemon on the Horizon? China’s Threat to East Asian Security,” International Security 19, no. 1 (1994): 149-168; Bill Gertz, The China Threat (Washington DC: Regnery Publishing, 2000); Richard Bernstein and Ross H. Munro, The Coming Conflict with China (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997); and more recently Aaron Friedberg, A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia (New York: Norton, 2011).

5. Roy, “Hegemon on the Horizon,” 159.

6. Hu Jintao said these words in a speech on January 20, 2011. See “Full text of Hu’s speech at welcome luncheon by U.S. friendly organizations,” Xinhua English News, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2011-01/21/c_13700418.htm (accessed June 20, 2013).

7. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, SIPRI Yearbook 2013: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security, summary (SIPRI: Stockholm, 2013), http://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2013/files/SIPRIYB13Summary.pdf (accessed June 16, 2013).

8. Amol Sharma et al. “Asia’s New Arms Race,” The Wall Street Journal, February 12, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704881304576094173297995198.html (accessed June 18, 2013).

9. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “Military Expenditure Database,” http://www.sipri.org/research/armaments/milex/milex_database (accessed June 17, 2013).

10. “Remarks by President Obama to the Australian Parliament,” November 17, 2011, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2011/11/17/remarks-president-obama-australian-parliament (accessed June 20, 2013).

11. Narushige Michishita, “Abe Doctrine to remake Japan-ASEAN relations,” The Straits Times, March 6, 2013.

12. Press Office of the White House, “Remarks by President Obama to the Australian Parliament,” November 17, 2011, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2011/11/17/remarks-president-obama-australian-parliament (accessed June 20, 2013).

13. World Trade Organization Statistics Database, “Trade Profiles,” http://stat.wto.org (accessed June 22, 2013).

14. David Shambaugh, “Introduction: The Rise of China and Asia’s New Dynamics,” in Power Shift: China and Asia’s New Dynamics, ed. David Shambaugh (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005), 42.

15. Yongnian Zheng, Globalization and State Transformation in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 52.

16. Ibid., 69.

17. Richard McGregor, The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers (New York: Harper Collins, 2010).

18. Paul Hirst, “The global economy—myths and realities,” International affairs 73, no.3 (1997): 411.

19. Leonard C. Turner, Origins of the First World War (New York: Norton, 1970).

20. Norman Angell, The Great Illusion: a study of the relation of military power in nations to their economic and social advantage (Toronto: McClelland and Goodchild, 1933), 26.

21. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, “US lambasts China for breaches of trade rules,” The Telegraph, December 26, 2012, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/globalbusiness/9765348/US-lambasts-China-for-breaches-of-trade-rules.html (accessed June 23, 2013).

22. See for instance Alexander Wendt, “Anarchy is What States Make of It: the Social Construction of Power Politics,” International Organization 46, no. 2 (1992): 391-425; Ted Hopf, “The Promise of Constructivism in International Relations Theory,” International Security 23, no. 1 (1998); and Hayward R. Alkar “On learning from Wendt,” Review of International Studies, 26 (2000): 141-150.

23. Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

24. David Shambaugh, China’s Communist Party: Atrophy and Adaptation (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2008), 41-81.

25. Suisheng Zhao, “A state-led nationalism: the patriotic education campaign in post-Tiananmen China,” Communist and post-Communist Studies 31, no. 3 (1998): 287-302.

26. As quoted in McGregor, The Party, 236.

27. Nicholas Kristof, “The rise of China,” Foreign Affairs 72, no. 5 (1993).

28. Dina Smeltz, Foreign Policy in the New Millennium. Results of the 2012 Chicago Council Survey of American Public Opinion and US Foreign Policy, (Chicago: The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, 2012), http://www.thechicagocouncil.org/UserFiles/File/Task%20Force%20Reports/2012_CCS_Report.pdf (accessed, 24 June, 2013).

29. See Yale Richmond, “Academic and Cultural Exchanges,” in US-Soviet Cooperation: A New Future, ed. Nish Jamgotch, Jr. (New York: Preager, 1989). On (academic) exchange in the Cold War see also Yale Richmond, Cultural Exchange and the Cold War: Raising the Iron Curtain (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003).

30. For more information on student exchange and the statistics for 2012, see “Research and Publications,” Open Doors, Institute of International Education, http://www.iie.org/Research-and-Publications/Open-Doors.

31. Richmond, Cultural Exchange and the Cold War, 29.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn

[…] problem is the very definition of China as the new enemy – in a new Cold War — upon which future American military planning is focused. We may get the very eventuality we […]