In seeking bilateral negotiations with North Korea, Japan focused on the abduction issue. It tried to steer the Six-Party Talks toward a comprehensive solution to this problem, as well as to the missile and nuclear threats from North Korea. And it has stuck close to the United States as it ramped up pressure on the North. Meanwhile, by striking a deal on the “comfort women” issue with South Korea, Japan sought more trilateralism in deterring the North. Recently, by improving ties with China, it pushed for tougher sanctions on North Korea. Since Prime Minister Abe began wooing President Putin in 2012, overtures to Russia for coordination to break the deadlock have also been apparent. Russia presents itself, sanctimoniously, as the sole intermediary capable of resolving the crisis over North Korea, and Japan keeps exploring whether that prospect is realistic, so far failing to find satisfaction in the responses.

Russian representatives emphasize Moscow’s history of alliance ties, its genuine support of reunification (on terms acceptable to both Koreas), and its success in building trust with Pyongyang, Seoul, and Beijing—qualities that make it the ideal interlocutor for finding a way forward in this intractable and dangerous crisis. In Abe’s talks with Putin, hopes were raised that a shared outlook on how to contain North Korea could serve as a breakthrough to shared understanding on regional security—critical to the relationship of trust sought by Abe. That is why their talks concentrated on the North Korean issue, although Japan’s most important interest with Russia has been the Northern Territories, including joint economic activities on the islands, which are seen as a condition of resolving the territorial problem. Yet, the positions in Tokyo and Moscow on North Korea have clearly become diametrically opposed: Abe is taking a hard line on maximum pressure approach with no trust in dialogue at least at this time, while Putin is insistent that sanctions do not work and pushes for immediate, unconditional talks. Russia criticizes that Japan only follows US policy, citing that they take a hard line on North Korea together. In this article, I examine Russia’s thinking about North Korea, casting doubt on its pretenses for ameliorating the crisis while recognizing why some are now tempted to find promise in such Russian idealism.

Below I examine the significance of North Korea to Russia, the relationship between recent Russian foreign policy and its North Korean policy, and the form Russia’s assistance to North Korea takes. The article addresses the arguments in support of a special role for Russia in resolving the North Korean crisis, while questioning their validity. It adds a Japanese perspective on prospects for working with Russia.

The North Korean Crisis at the End of 2017

Many believe that today’s greatest threat to the world has shifted to North Korea. In spite of repeated criticism from the international community, Chairman Kim Jong-un has continued his nuclear tests and missile launches, most recently testing North Korea’s most powerful ICBM to date, a “Hwasong-15 missile.” North Korea has already reached its goal of developing the capacity to reach all parts of the United States (although the ability to deliver a nuclear payload and to achieve reentry is uncertain), it has several times sent missiles into the atmosphere over Japan. With the suspected torture death of an American student and the issue of abducting Japanese citizens on which there is no progress, Japan and the United States find their grievances only deepening. As December begins, there is more talk in Washington of a preemptive military action, while in Moscow pushback is more pronounced, warning against such action.

The United States and Japan are continuing to take a tough stance toward North Korea, intensifying pressure through economic sanctions. Donald Trump has repeatedly criticized Kim Jong-un, taunting him with nicknames such as “Rocket Man.” On November 20, it was announced that Trump had decided to redesignate North Korea as a “state sponsor of terrorism,” and on November 21, additional sanctions were announced with the idea of adding pressure to squeeze the North.

In contrast, doubts are being raised about the “Moonshine policy,” advanced by President Moon Jae-in of South Korea, which prioritizes dialogue with North Korea. South Korea is finding it hard to follow a softer line due to the North’s continued provocations, but that may change. China and Russia continue to emphasize “dialogue” with North Korea and oppose the Japanese and US approach. Even so, since the fall of 2016, China, which exerts the greatest influence over North Korea, appears to have hardened its posture toward the North. Against the background of the persuasiveness of the United States and others, and also the reality of the relative flexibility of Europe and the United States on the contents of the sanctions, even China, steaming over North Korea’s repeated provocative behavior, has agreed to toughen the sanctions resolutions, most recently at the September 11 Security Council meeting. Despite hesitantly approving the sanctions resolution, Russia continues to assist North Korea and sees itself as a necessary presence making it easier for North Korea to persist.

An Overview of Russia-North Korea Relations

From 1948, North Korea, which was brought into this world by Josef Stalin as an important outpost in order to expand the sphere of influence of socialism in the Cold War era, received substantial assistance from the Soviet Union as Asia’s second socialist country. Especially as a result of the conclusion of the 1961 Soviet Union-North Korea friendship treaty, the alliance relationship intensified, but due to the Sino-Soviet split and a more pragmatic Soviet strategy, relations were usually not very close.1 From the time Mikhail Gorbachev’s regime began in 1985, relations with North Korea weakened. Even so, military and other assistance continued with the delivery of the final Mig-29s in 1989, and there was no mistaking the importance repeatedly given to North Korea by the Soviet Union. If in 1990-91 Gorbachev chose a different course, the legacy remained deeply imprinted.

After the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, Boris Yeltsin moved to build ties to South Korea, and, despite misgivings about loss of clout from the time of the nuclear crisis in 1993-94, ties with the North notably advanced only under the Putin administration. In 2000, the “Russia-North Korea Friendship and Good-Neighbor Cooperation Treaty” was signed in February, and Putin visited North Korea and promised Kim Jong-il to strengthen bilateral relations in July, followed by cooperation in various fields. While nuclear weapons and other issues have aroused tensions in bilateral relations, Russia values its international presence in dealing with the North Korean question, prizing its participation in the Six-Party Talks in order to resolve the nuclear question through dialogue and counting on a special relationship with the North to prevent it from being marginalized in maneuvering.

Russia’s interest in North Korea has again heightened as its foreign policy changed. Before Putin resumed the presidency in March 2012, due to the contrast between the extreme deterioration of European economic conditions and the improvement of those of Asia’s economies, diplomacy gravitated toward Asia. In its shift to Asia, Russia found the China factor especially important. As a “near neighbor” with booming economic development and a rapidly advancing world role, China aligned with Russia in its policies toward the United States and in the Middle East. Given latent tensions with China, Russia is said to value relations with Japan as a partner in trade and exports of energy and as having great latent importance for Russia’s turn to Asia, including for the important goal of freeing itself from excessive dependence on energy for its economy. In the tensions that peaked with the Ukraine crisis of 2014 and accompanying sanctions, the Russian economy was battered.2 This led to doubling down on its “turn to Asia,” increasing reliance on China, showing limited interest in talks with Japan and intensifying interest in North Korea as a means to gain influence in Asia.

North Korea’s Importance for Russia’s Asia Policy

For Russia’s advance in Asia, the Korean Peninsula serves as an important gateway. It envisions the “Rajin-Khasan transport project” as a huge investment, enabling the export of Russian products, including coal, and as the opening wedge for a thriving vertical corridor extending through South Korea transforming the geo-economics of the Russian Far East.3 Some may surmise that the ideal scenario for this would be the reconstruction of North Korea under South Korean leadership in a process of reunification, but Russians favor an alternative process, whereby the powers agree to North Korea’s limited willingness to open its borders to infrastructure projects, trusting Russia to support its continued autonomy. Thus, from about 2011 even before Putin articulated his notion of an “Asia pivot,” one could detect the sprouts of Russia and North Korea drawing appreciably closer.4

From early in the 2000s, Russia was positively advocating plans to connect the Trans-Siberian Railway and a trans-Korean railroad as well as constructing a gas pipeline from Siberia to South Korea. Even earlier from about 1992, it had explored a three-country development plan for the Tumen river basin with China and North Korea, although many Russians were nervous that the result would be a growth center that would lead to the atrophy of Russia’s Far East. This plan was replaced by designs for making North Korea an important economic focal point for Russia, both through leasing a wharf for 49 years in Rajin port while linking it to Russia through transport improvements with mineral exports in mind, and through strengthening economic ties to South Korea to realize corridors across North Korea.5 If such multilateral (Eurasia-level) economic projects succeeded, they would be convenient for North Korea, allowing it to escape from extreme dependence on China.6 Russia saw an opening to entice North Korea toward a strategy favored by Russia.

Until recently only China could exert influence, however limited, on North Korea, with its Asia shift Russia was trying to extend its influence over the North, and from 2014, Russia was notably intensifying this effort. Facilitating this was the attendance of Kim Yong-nam at the February 2014 Winter Olympics. Another official of North Korea Hyon Yong-chol subsequently made two visits, discussing intensification of military relations with Russian officials. Just at that time China was cutting back on economic assistance, angry over the December 2013 purge of Chang Song-thaek, which became the background for Pyongyang to decide to draw closer to Moscow. Isolation in the Ukraine crisis led Putin to stress Asia more, heightening its interest in North Korea.

In 2015, however, Hyon, the pipe to Russia, was purged and Kim Jong-un, who had been expected to visit Moscow for the 70th anniversary celebration of the victory in WWII, indicated that he would not attend, leaving Russia’s North Korea policy on shaky grounds. Moreover, Russia could not overlook before the eyes of international society the repeated missile tests and nuclear tests of North Korea. Later it joined in sanctioning North Korea at the United Nations. On April 4, 2017 Putin announced new sanctions prohibiting imports of North Korean silver, tin, nickel, and zinc, but all of these products are produced in Russia too; willingness to go along with the Security Council resolution could be viewed as a mere gesture.

In reality, Russia does not have the power to stop North Korean provocations. Unlike China, it does not have the means to exert influence on the North Korean leadership; it only maintains a diplomatic route through the embassies of the two countries. Through political pressure and economic sanctions, it cannot affect the North. However, the reality is that the United States would like Russia to exert pressure on North Korea. There have been repeated reports that Trump would like to rely on Russia for arranging a US-North Korean summit in 2017. Also in November 2017 in order to request cooperation in strengthening the isolation of North Korea, Trump was reported to have conducted a telephone conversation with Putin lasting as long as one hour. Trump’s interest in Putin’s help adds to Russian expectations.

Even so, apart from somewhat compromising its relations with North Korea by agreeing to sanctions against it, Russia has generally been uncooperative with the United States, stressing resolving problems with North Korea through dialogue and frequently speaking on behalf of North Korea. Russia emphasizes that the United States makes North Korea feel unsafe and that to the extent that the United States conducts joint military exercises with Japan and South Korea and deploys the THAAD missiles, North Korea will not stop its provocative missile and nuclear tests. This is close to the honne of Russia, since it regards the deployment of US forces in Asia as a big threat to Russia. It uses the North Korea situation to express its own wishes. While Russia will not necessarily protect North Korea, there is no doubt that it will go on assisting the North as a result of this geopolitical reasoning about Asia.

For Russia, North Korea’s continued existence has important significance from the standpoint of security, and its importance is increasing. US forces in Japan and South Korea and the deployment of THAAD in South Korea are matters of great concern in Russia, making North Korea a buffer zone. In contrast, if North and South Korea were unified under South Korean leadership, there would be a high possibility that US forces would be deployed close to the Russian border, which would be perceived as a great danger to Russian security. It wants to avoid a threat in the east similar to its existing concern about the threat from NATO on its western borders. This gives Russia a big incentive to assist North Korea’s continued existence. In this way, Russia can, while posing to put some distance between them, strengthen its relationship with North Korea for reasons of addressing its security concerns, emphasizing its Asia-oriented diplomacy, strengthening its international status, and anticipating an economic future beneficial to the Russian Far East and to the ability of Russia to remain an autonomous force in East Asia apart from China.

North Korea’s 2017 Provocations and the International Responses

In 2017, repeated North Korean provocations—nuclear tests, missile launches, torture of an American student leading to his death, and the suspected murder of Kim Jong-un’s half-brother Kim Jong-nam—were reasons that various countries were now cornering North Korea. In 2017, there were many missile launches and a sixth nuclear test. US attention was particularly drawn to the August 9 declaration in KCNA that a medium-range missile attack on the US Pacific island of Guam was being considered. Although no such launch occurred, the view prevailed that because the missile that went over Japan could reach Guam if its trajectory were changed, the report of this missile test by North Korea meant that the threat was real. Alarm only mounted with a later launch of a new ICBM with a longer range.

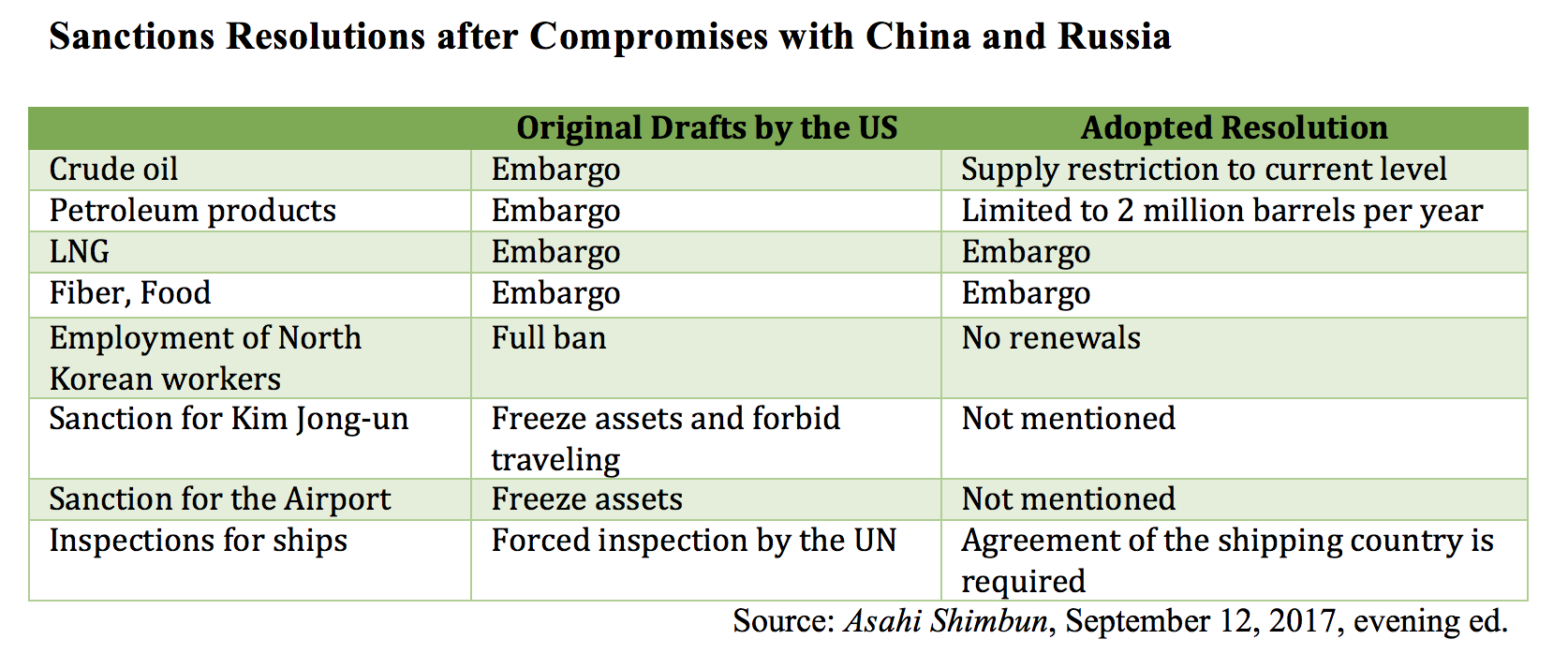

Through its September nuclear test, North Korea cut the cord of Chinese and Russian patience, which had stressed the path of dialogue and fiercely opposed a ban on oil deliveries. Although both had to this point opposed a new round of sanctions on North Korea at the United Nations, given the reality of US persistence and concessions, as seen in the table below, they reached the point of supporting tougher sanctions on the North.

In 2017, there was also a closer look at North Korea’s violation of human rights, when it sent home the dying American student, Otto Warmbier, whom it had arrested 1½ years earlier over theft of a poster. This angered the American public and drove Trump to harshly criticize North Korea’s human rights record, taking the opportunity to tighten cooperation with Japan in resolving the most vexing problem it has with the North, the “abduction issue.” Kim Jong-un’s assassination of Kim Jong-nam in February 2017 at a Malaysian airport influenced international policy toward the North too. This was cited in November when Trump, after a 9-year interval, redesignated North Korea a state sponsor of terrorism, demanding maximum pressure against it. North Korea’s international image deteriorated even further.

While new Chinese sanctions were cutting back on dealings with North Korea, China opposed the redesignation, and Russia charged that it could exacerbate tensions, warning of the possibility of causing destruction on a global scale. Kim Jong-nam had Russian connections. His mother, a former actress whose marriage to Kim Jong-il was not recognized by his father, had lived in Moscow after being divorced from and had died in 2002. The son had not forgotten her and was said to have visited Russia from time to time, and was even able to speak some Russian. When she died, following North Korea’s wishes, she was buried in Troitskoye cemetery, one of the highest status burial grounds in Russia, and Kim Jong-nam was in attendance when the tombstone was erected. Given this connection, Russia would not be expected to be well-disposed to the assassination; however, the four North Koreans, who had been held on suspicion of involvement in the incident before leaving Malaysia, flew across Jakarta, Dubai, Moscow, and Vladivostok to reach home and when South Korean intelligence asked that they be stopped in Russia from going to Pyongyang, Russia refused, and they were allowed to leave. This led to the view that Russia is cooperating with North Korea.

Through its provocations, North Korean has deepened its international isolation, especially dealing a blow to its ties to China. Early in 2017, China had already begun to reduce its assistance to the North, and as Sino-US ties were improving, this tendency grew more prominent. One objective of the November 2017 Trump visit to Asia was to strengthen linkages with Asian countries on the North Korean question. Japan completely agreed to the program of intensifying pressure on North Korea. Welcomed in China like an “emperor,” Trump tightened cooperation in dealing with North Korea. China is said to be closely cooperating on blocking trade. For North Korea, the heavy blow of the United States and China drawing closer together makes Russia’s presence extremely important, more than before.

Russia’s Indispensability for the Survival of North Korea

Hoping to preserve North Korea in its current system, Russia, while criticizing the provocations of North Korea on the international stage and participating in limited sanctions, is strongly opposed to intensifying pressure, which Japan and the United States advocate, and instead, insists that use of military force must be prevented.7 This is not only because of the high possibility that North Korea would be destroyed should the United States and others use force against it—which would result in crowds of North Korean refugees flooding into Russia, and strike a blow against Russia’s international strategy—but because it is thought that domestic unrest in Russia would result. Because Russia strongly desires the persistence of the Kim Jong-un system, it advocates resolving various North Korean issues on the basis of dialogue and, in spite of wielding almost no real influence on the North, it is continuing to put its diplomatic weight behind asserting itself for a go-between role.

With China drawing closer to the United States, North Korea, whose economy has revolved around China for both assistance and trade, is trying to fill the vacuum by strengthening relations with Russia. Russia not only is using various underhanded methods to supply oil and goods to North Korea, as it is enabling telecommunications and transport while making its own existence indispensable for North Korea, it is also using cheap North Korean labor, creating the reality that bilateral ties are replete with mutually dependent relations. Below, I identify notable developments in bilateral relations.

First, there is material assistance for North Korea to evade the sanctions. The United States is trying to cut off oil supply to North Korea, and China and Russia, the main suppliers, are fervently opposed. It is said that China supplies about 500,000 tons a year of crude oil and 210,000 tons of refined oil, while Russia mainly supplies 200,000-300,000 tons of crude oil. Since North Korea’s annual oil demand is 900,000 tons, it relies on China for more than half its needs. It was stressed that Russia over a long period exported essentially zero oil and petroleum products to North Korea, but in 2017 the amount notably increased. In the first quarter, bilateral trade more than doubled to $31.4 million, the main reason being increased export of petroleum products. By October, at least 8 shiploads on North Korean registered ships had delivered fuel shipped from Russia, nominally targeted to third countries, but in fact returning to port in North Korea. These are strategies widely used in order for North Korea to evade sanctions. There are numerous cases where China is named as the destination from Russia but the shipments are actually destined for North Korea. If the expectation in the sanctions is that North Korea’s coal exports, which are the main source of income for North Korea, would disappear, they may still be possible. In June 2017 when a ship that had set sail from China entered a North Korean port, its geo-positioning system was turned off, and after coal was loaded on board it took a detour and the system was reactivated, it stopped in a Russian port, and then, loaded with coal, returned to China. On the surface, there remains no evidence that the ship entered North Korea, and it appears as if the coal was imported from Russia. Using Panama- and Jamaica-registered ships, there is a considerable amount of North Korean coal transported to China and Russia,8 with estimates that the North earns more than $1 billion a year from coal exports.

Second, Russia has begun new forms of assistance in communication, transportation, and tourism. One lifeline for North Korea is the cargo ship Mangyongbong, which had linked Japan and North Korea before Japan imposed a complete ban on imports in 2006. In May 2017, it began regularly operating from Vladivostok to Rajin; due to an increase in charges for using the port of Vladivostok from fear of US sanctions it stopped sailing at the end of August, but in early October, it was operating again as an “irregular transport only route without carrying passengers.” While this ship’s operation by itself does not violate the sanctions, there is a danger that it will create a pathway for the export and import of goods that are prohibited unless, without agreement on fees for use of the port, the regular route proves sustainable by cargo alone and is closed again. Also at the end of August, in Moscow, the first North Korean travel agency was opened. The aim is to facilitate travel to North Korea, shortening the time for issuing visas for Russians from 2-3 weeks to 3-5 days. The North Korean embassy in Russia is trying to appeal strongly to the safety in travel to North Korea, and this move too is a symbol of the tightening relationship of Russia with North Korea. Moreover, on October 1, North Korea established a new Internet connection through Russia, replacing connections dependent on China. This deepens alarm in various countries intently watching the upgrading of North Korea’s cyberattack capabilities.

Third, there is the issue of labor coming from North Korea, which has great merit to both Russia and North Korea. According to 2015 statistics, 47,000 North Korean workers labored in Russia, a figure that excludes persons who had married Russians as well as illegal workers. From the official data, an overwhelming share of North Korean workers abroad are in Russia (China is second with an official total of 19,000 individuals). On March 22, 2017 at a Russia-North Korea gathering in Pyongyang concerning migrant labor Russia revealed a medium and long-term plan for expanding these numbers. For Russia aiming to develop its Far East, the North Korean labor force—efficient at low wages—is seen as indispensable. Additionally, in the construction of the 2018 World Cup Zenit (Gazprom) Arena, it was reported that many North Korean workers were involved. They roughed it out in containers that were moved to a site enclosed by barbed wire and worked about 17 hours a day for roughly $10, leading to criticisms of slave labor.9 Russian analysts warned that slave labor is not ending since the North Korean government is selling the workers to Russian enterprises.

Finally, the Putin administration is trying to present itself as a viable intermediary between North Korea and the United States, Japan, and South Korea, by deepening relations with North Korea and winning its trust. It is looking for an opportunity to realize dialogue by inviting representatives of North and South Korea to an international conference in Russia. For instance, at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok in the first part of September, Minister for External Economic Affairs, Kim Yong-jae, attended, trying to elicit from Russia expanded trade and investment and economic assistance. However, local residents of the Russian Far East were distrustful given the recent nuclear test and missile launches, and showed dissatisfaction at the way the Russian government was treating North Korea. At the plenary session, Putin emphasized the path of dialogue with North Korea, advocating the Sunshine Policy to achieve a breakthrough by getting the North to participate in various schemes for regional economic cooperation. In contrast, Moon Jae-in at the forum declared that nuclear and missile disarmament would allow economic cooperation of North and South Korea with Russia to proceed forward. Casting doubt on the realism of South Korea’s idea, Russia restrained from responding too sympathetically.

In addition, on October 16, the chair of the Federation Council Valentina Matviyenko met separately with North and South Korean delegates, participating in an international conference in Saint Petersburg, and called for direct talks between the two countries without drawing a negative response from North Korea. She met for about 1½ hours with the North Koreans in contrast to about 30 minutes with the South Koreans, and afterwards asserted that one should aim at reopening the Six-Party Talks on the North Korean issue and urged Russia to make maximum efforts to that end. In addition, from October 19, at a conference in Moscow on nuclear non-proliferation, Russia tried to encourage direct contacts between North Korea’s director-general for North America Choe Son-hui and US undersecretary of state Wendy Sherman.

Russia is active in building strong “pipes” to North Korea. Its parliamentary group visited the North in the first part of October and, continuing talks with high officials, TASS head Mikhailov was there on the 11th meeting with Foreign Minister Ri Su-yong. TASS introduced Ri’s position that the atmosphere does not exist for talks with the United States, which keeps conducting military exercises. Russia keeps building personal ties to North Korea and echoes its positions while deepening relations of trust, attempting to secure for itself the position of the intermediary. In the background to these efforts by Russia is the notion that if it becomes the go-between on the North Korean question, it will not only increase its influence in East Asia but also acquire an important diplomatic card to use against the United States.

Conclusion

Russia’s assistance to North Korea is motivated by various reasons, such as its international strategy, need for North Korean labor force, economic potential, and security buffer. Yet, North Korea for Russia is not a vital interest. Although Russia has almost no influence over the North, it reasons that North Korea can become an ideal partner in order to gain control over the international situation. The fact is that it is not easy to settle on a sustained strategy toward North Korea. For example, the plans for a railroad and pipeline down the peninsula are blocked by the United States and South Korea, and the posture of North Korea presents a further barrier. Given Russia’s isolation from Europe and the United States due to the Ukraine crisis, Russia is using the deepening tensions over the Korean Peninsula to serve its interests to the extent possible. When in 2017, China was drawing closer to the United States, agreeing to tougher sanctions against North Korea, one could not reject the possibility that Russia too would abandon North Korea. Russia also wanted its frozen relations with the United States improved. However, given the fact that sustaining its influence in Asia and having North Korea as a buffer are of great importance due to Russia’s current isolation from Europe and the United States, one can expect that, while engaged in a tug-of-war, it will continue to assist North Korea.

Not only the United States, but also Japan wants Russia to stop providing support to North Korea, concerned that this compromises the effectiveness of sanctions. Although Japan takes a tough stance against North Korea, it longs to avoid war, which is the position of Russia and China. That is why Japan keeps looking for ways to cooperate with Russia on the North Korean problem, and achieve a resolution by peaceful negotiations once North Korea stops its reckless behavior. There is also talk that Japan could play a role in the new negotiations because Russia would welcome it as long as there is no doubt that Japan would not merely reinforce the US position.

If Japan could cooperate with Russia on the North Korean issue, it would be one means of confidence-building with Russia, helpful in improving relations whether for limiting the Russian tilt toward China or enabling a breakthrough on the islands. How Japan can stop Russian support for North Korea and find a path to cooperation on this problem is a difficult challenge for Japanese diplomacy in Asia. While some outsiders worry that such hopes in Japan only reinforce Russia’s confidence, which benefits from closer ties to North Korea, and undercut coordination in dealing with Moscow on this issue, Japanese continue to pursue special ties with Russia based on the Abe-Putin relationship.

1. Alexander Lukin, “Russian Strategic Thinking Regarding North Korea,” in Gilbert

Rozman and Sergey Radchenko, eds., International Relations and Asia’s Northern Tier:

Sino-Russia Relations, North Korea, and Mongolia (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

2. Hirose Yoko, “Silk Road keizaiken koso to Churo no rigai tairitsu,” in Yukawa Kazuo ed., Chugoku tono kyori ni nayamu shuen, Asia Daigaku Ajia kenkyujo, 2016.

3. Gilbert Rozman, “The Russian Pivot to Asia,” in Gilbert Rozman and Sergey Radchenko, eds., International Relations and Asia’s Northern Tier.

4. Stephen Blank, “Making Sense of the Russo-North Korea Rapprochement,” in International Relations and Asia’s Northern Tier.

5. Liudmila Zakharova, “Economic cooperation between Russia and North Korea: New goals and new approaches,” Journal of Eurasian Studies, No. 7, 2016, pp. 151-61; Artyom Lukin and Liudmila Zakharova, “Russia-North Korea Economic Ties: Is there More Than Meets the Eye?” Foreign Policy Research Institute, 2017.

6. Lee, Jae-Young, “The New Northern Policy and Korean-Russian Cooperation,” Valdai Papers, No. 76, 2017.

7. Samuel Ramani, “Russia’s Love Affair with North Korea: The Logic behind Moscow’s Economic Outreach to Pyongyang,” The Diplomat, February 13, 2017.

8. UN Security Council passed the resolution to restrict coal exports from North Korea in 2016; and China announced the suspension of its transactions with North Korea in February 2017, however China has not abided by this.

9. It is said that the usual monthly salary for a worker from North Korea is about $450 and 80% of the salaries have been sent to North Korea.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn