Sanctions are changing North Korea but not in ways expected by the world community imposing them, or by the Kim regime that is fighting them. Clearly, they have not yet succeeded in stopping North Korea’s nuclear program and, arguably, not even slowed it. But equally clear is North Korea’s increasing isolation from the global economy and, more importantly, loss of aid receipts that, until a few years ago, kept the regime barely afloat. To make up for these lost resources, Kim is accepting elements of a market economy that his father and grandfather had shunned, and which threaten Stalinist controls on the population, especially through the nearly defunct public rationing system. Ironically, the rise in private productivity that these new competitive activities is enabling, especially in the services and construction sectors, and possibly in farming, is creating progress that may allow Kim to think he is indeed achieving “byongjin,” the simultaneous development of nuclear weapons and economic progress. But he, or at least his more experienced advisors, likely understand that market activity, carried too far, presents an enormous risk to the country’s bedrock controls and that Kim may have “mounted the (capitalist) tiger” of Chinese legend. With much stronger sanctions coming into play—China a year ago stepped up with economy threatening measures, and results are just now showing in its trade data—the verdict is still out on their ultimate impact. There are signs, still ambiguous, that the economy may turn against Kim. Smarter and stronger sanctions, used as precise instruments rather than blunt tools, might create wedges inside the North Korean command economy, but much depends on how well the sanctions are used and what risks Kim will take with his economy. If the sanctions are to succeed, he will have to see the nuclear program as adding to, rather than subtracting from, these economic and security risks.

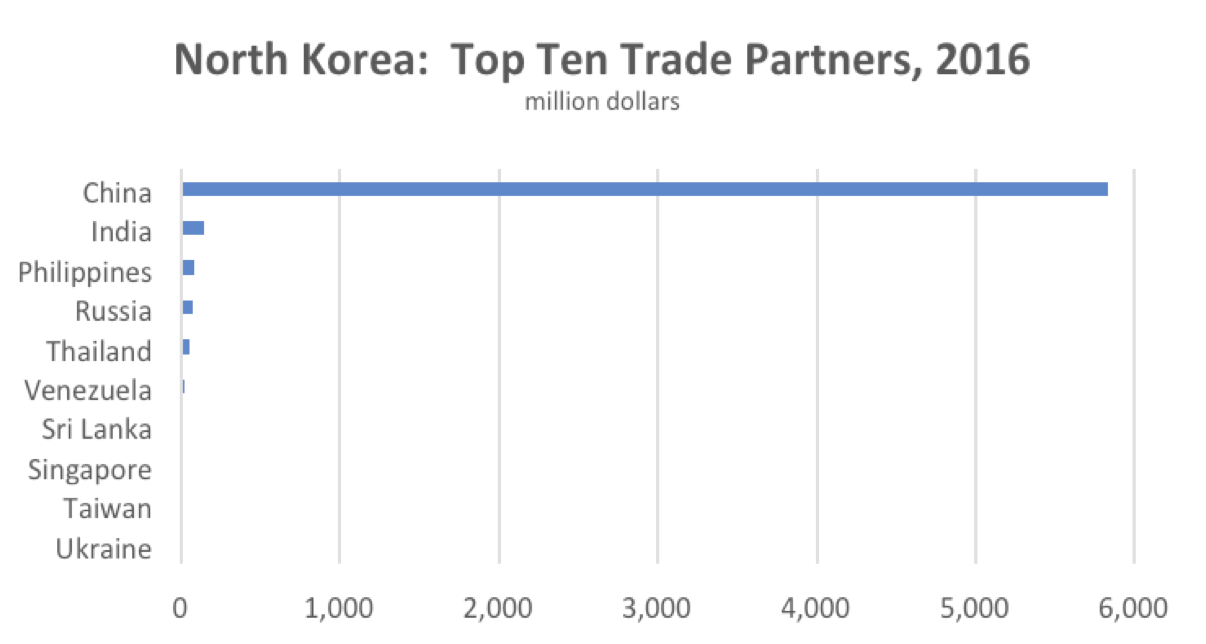

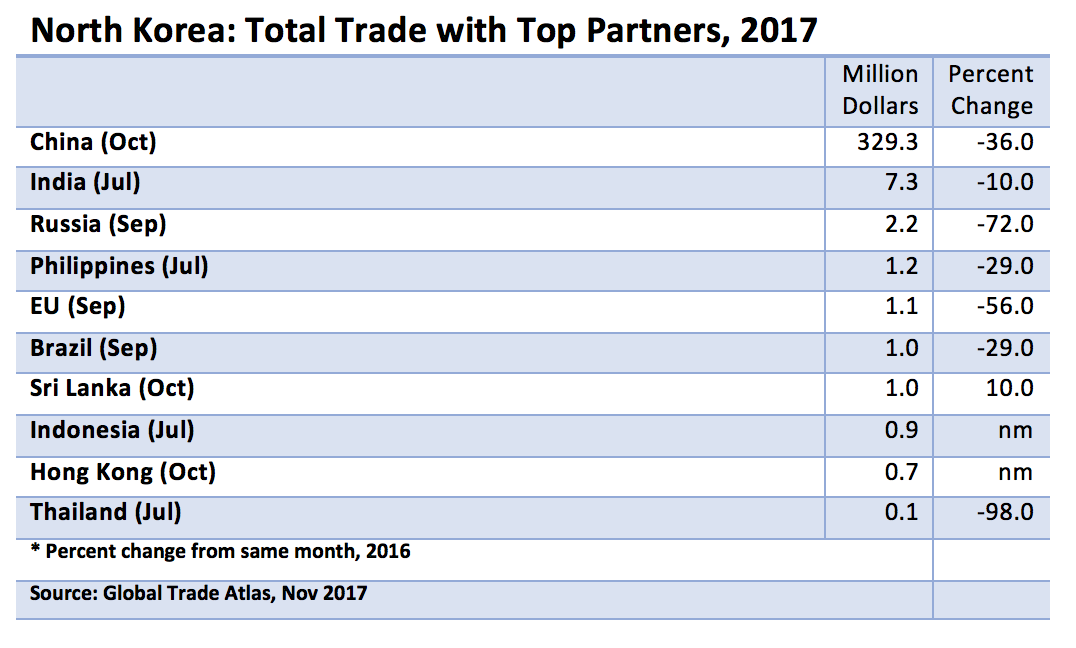

The “Hermit Kingdom” has been a misused moniker for North Korea for better than half a century but, if the latest UN Security Council sanctions are enforced, it may soon be all too accurate. As the graph and table below demonstrate, economic relationships with virtually all countries are collapsing as the most recent UN sanctions have come into play. China plays the only consequential partner remaining, accounting for 91 percent of North Korean exports and imports, as tallied by partner data in 2016.1 Even its trade was plummeting as of this October, down 36 percent from October 2016. When sanctions were first imposed in 2006, just after its first nuclear test, trade was far more diversified: China 38 percent; South Korea 30 percent; Japan and Russia about 5 percent each; and the rest of the world 22 percent.2 Before that, the Soviet Bloc, Western Europe, and Japan were large partners.3 Debt defaults, the collapse of the Bloc’s fixed price trading agreements, and angry episodes with Japan and South Korea progressively cut into Pyongyang’s trade through the early 2000s.

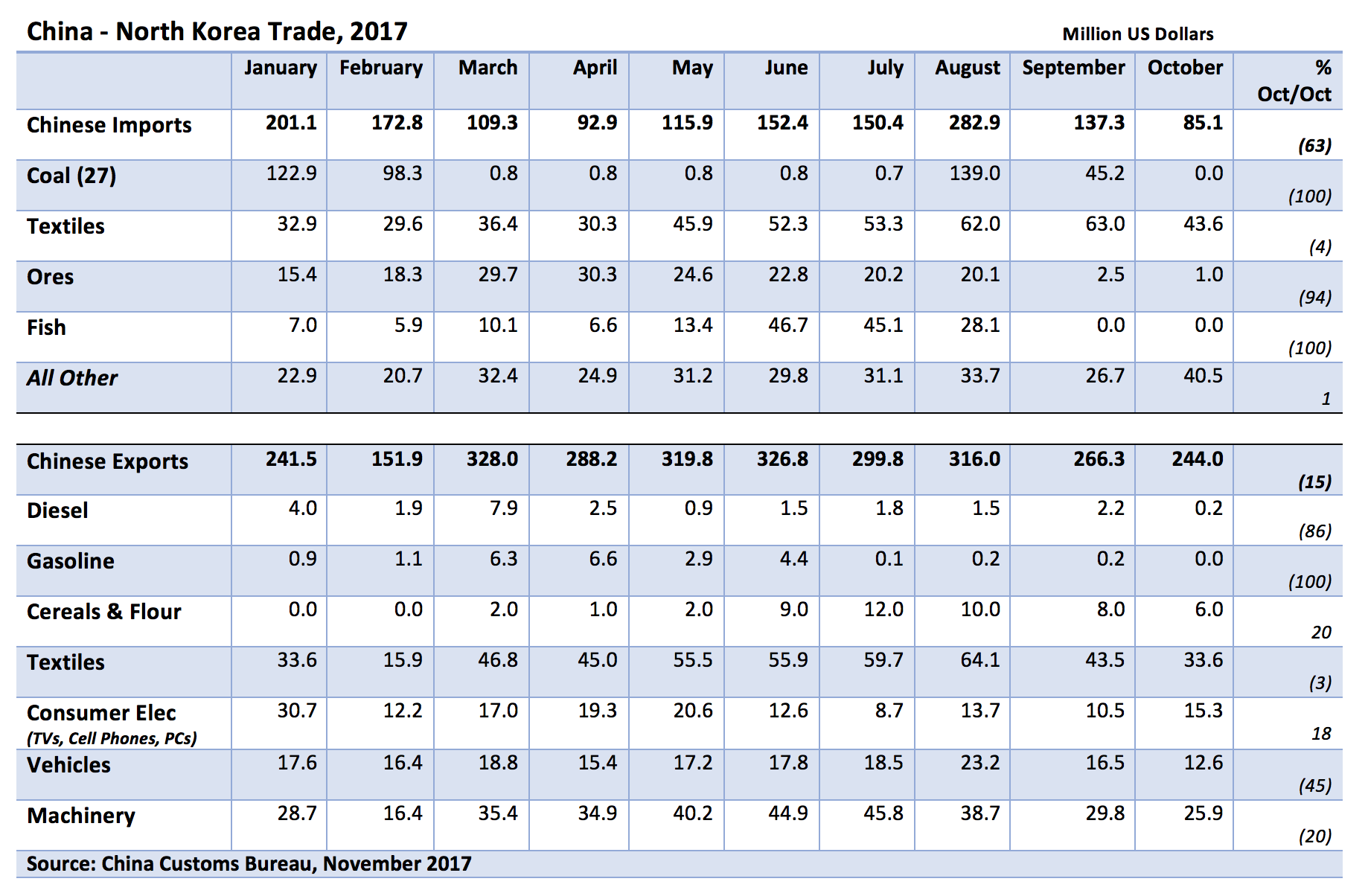

UN Security Council sanctions have added to a litany of issues not related to nuclear weapons development, which have funneled almost all North Korea’s foreign trade through China. The value of this trade surged spectacularly through last year, with rising coal, oil, and metals prices, and with China’s vastly improved capacity to produce consumer goods and electronics, which are in high demand in North Korea’s evolving markets. But late last year, China finally signed onto much tougher UN sanctions, reinforced this year in August and September, that have hit hard on North Korea’s major exports—anthracite coal, non-ferrous and ferrous metals, fish products, and textiles. China’s own exports to North Korea have been less impacted, causing a big and likely temporary increase in China’s surplus—$1.5 billion in the twelve months through this October—which is probably draining North Korea’s funds and reducing its ability to import needed products. Declines in refined petroleum products and industrial goods, and maybe even grain, will likely spread to other products in coming months. North Korea is increasing its export of non-sanctioned goods, such as fruits and vegetables, but it is doubtful they can compensate for the big earners.

As the graph shows, the data for October was particularly significant with North Korean sales to China down 60 percent from October 2016, and imports down 15 percent, as the UN Security Council Resolution 2375 sanctions began to take effect.4

For the month, as required by the sanctions, China reports that it imported no coal, iron or non-ferrous metals ore, or fish products—previously North Korea’s largest foreign exchange earners. Textiles declined and are slated to fall to zero in coming months. Fruits and nuts have risen to second place in North Korea’s exports, and these are high only in the autumn months. Whereas the drop in refined product imports is apparently causing soaring prices in North Korea, crude oil shipments, traditionally provided as part of a decades-long government-to-government aid agreement, presumably continue. Consumer goods imports, generally sold at market prices and often in renminbi or dollars, are holding up relatively well, but investment goods, such as machinery and transportation equipment, are falling, possibly indicating that state enterprises that buy them are under budgetary pressure.

Monetary impact of sanctions not yet evident

Curiously, the tripling in North Korea’s goods trade deficit to $1.5 billion in the twelve-months through October, from about a $500 million twelve-month rate over the past five years, has not hurt the value of the North Korean won in informal marketplaces, where it appears to be traded freely for dollars and renminbi.5 North Korea probably runs a surplus on the rest of its current account—net services income, remittances from overseas Korean workers and relatives, and some aid from UN agencies and others. Since the country is effectively bankrupt, new borrowings or inward investments are virtually impossible, so net capital account income is zero and the current account must be self-financing except for use of reserves. It is difficult to see, however, how the non-goods component of the current account could be rising to cover this rising goods deficit, especially since new sanctions target overseas workers and their remittances as well. Spending of foreign exchange reserves could pay for some of the imbalance, but these are not large enough to last for long, and mostly, presumably, are controlled by Kim himself, so he would feel he is spending his own money.

Questions thus arise as to how long the regime can maintain this monetary stability, especially the nearly fixed dollar exchange rate, and what will happen if its citizens suddenly lose confidence, as they have on several occasions in the past, when the won was forced to devalue by orders of magnitude and inflation soared. Money, either won or dollars, was much less important than it is now, and in today’s money-driven North Korea, panic could easily erupt, at least among the monied elites and the merchants. Short of that, one can expect declines in imports with consequential impact on prices and availability of consumer and investment goods.

Understanding these dangers, monetary authorities are no doubt keeping a close eye on the informal exchange rate and may even be intervening—spending reserve dollars and renminbi—to keep won fixed at the 8,000 per dollar rate. Interventions such as these can be painless if the public accepts the power of the state to enforce the rate, but a significant price movement in favor of the dollar, for instance caused by a missile or nuclear test and calls for new sanctions, could lead to panicked selling of won, subsequent hyperinflation, and turmoil for the growing class of money lenders. Meanwhile, monetary authorities, seeking to defend the value of won, are not likely providing much credit for state enterprises and government agencies, forcing the state to try to raise funds wherever it can and crimping the already extremely low state wages.

So far though, there has not been much market reaction to the visible trouble in the trade sector. The biggest exception is the doubling in the market prices of gasoline, diesel, and kerosene fuels last summer—prices that have stuck at a high enough level to induce smuggling—presumably due to the decline in refined product imports–and hoarding as merchants anticipate new sanctions on imports. Also evident are new campaigns to raise government income by charging tolls and, possibly, raising sharply the price of electricity.6 With strong sanctions only a month or two old, one would think it is a nervous time for North Korea’s growing class of money lenders and foreign exchange traders and certainly for anyone in charge of Kim Jong-un’s money reserves.

Mythology of sanctions

Recent western commentary on the sanctions has been extremely negative, and for obvious reasons.7 They have not worked to stop the nuclear program, and not for lack of effort. UN and specific country sanctions have been employed in escalatory fashion since Pyongyang set off its first nuclear test in October 2006. The Security Council has passed nine unanimous resolutions, each adding to the former, culminating by now in blanket prohibitions against member states importing North Korea’s major export commodities, and limiting vital refined petroleum shipments and scientific and military equipment exports to North Korea. North Korea’s overseas workers and joint ventures are close to being banned as well. Sanctions now go far beyond the initial steps, which were aimed specifically at nuclear and missile production. Gone are most Chinese and Russian caveats that UN measures do not hurt the “livelihood” of North Koreans, a loophole that for years voided any real pressure on the economy at large.

Many reasons are given for the sanction regime’s failure, especially compared with what are sometimes considered successful sanctions against the Iranian regime. The best explanation is that no one ever expected, or intended, sanctions to be the only tool to stop the nuclear weapons program. Other kinds of force, or incentives, have always been considered necessary to change Pyongyang’s behavior but these other tools have never actually been applied.

Other explanations for the sanctions failures bear evaluation and lessons drawn to understand whether they can become more effective. Four issues we consider are: 1) the idea that the self-isolated regime and its juche (self-reliance) philosophy make it impervious to outside influence; 2) the assertion that there is no US leverage since it has maintained unrelenting restrictions on North Korean commerce since the Korean War and cannot make them any tighter; 3) unwillingness of China to use economic measures that could seriously threaten regime stability; and 4) the high priority of Kim places on obtaining nuclear weapons, which he believes will secure the regime’s safety even as it threatens to crush their South Korean rival.

Myth one: North Korea’s juche ideal

One of the larger ironies in the North Korean sanctions saga is the fact that North Korea’s crippled, but still partially planned economy may need external sanctions for its own survival. A planned, or “command” economy in a world without them needs to be self-reliant, or at least tightly controlled, and sanctions breed such self-reliance. This may partially account for the regime’s unwillingness to let sanctions get in the way of its nuclear program. Some might even argue a reverse logic; the nuclear weapons program may be designed to keep outside capitalist influences at bay, and sanctions only help. This is not to say that sanctions, or self-reliance, helps the North Korean economy, or people, at large; quite the opposite. By all considerations, North Korea, if not the ruling regime, would benefit greatly from being an integrated part of the world trading system, taking advantage of its excellent geography, natural resources, and built-up human and physical capital stock. And, as much as the regime parrots a juche philosophy, it has never, until now, been anywhere close to that ideal.

North Korea, in its socialist heyday, though not a formal member of COMECON was a solid participant in the Soviet Bloc, trading extensively with its members and with a logical division of labor and specialization evident through the linked planning mechanisms of these states. After the Korean War, this allowed it to build on the foundations of colonial Japan a significant heavy industrial and machine-building industry. Later it recreated a strong trade relationship with Japan, which had built extensive infrastructure—rails and ports—to facilitate imperial trade. As China’s trade-oriented economy developed, trade with its next-door neighbor increased as well, at first through communist-style fixed price trade arrangements and barter—especially Chinese coal in exchange for North Korean anthracite. Gradually, however, they adopted market-based trade, after Beijing discarded its planned system in the 1980s and as the North Korean authorities were powerless to stop the influx of Chinese products across their long, porous border. For a period in the mid-1970s, even Western Europe was a major trade partner as investment credits and bank loans were offered to develop North Korea’s mineral and metals exports, an effort that collapsed in North Korea’s bankruptcy after commodity prices plunged and reforms failed to catch on. Later, progressive governments in South Korea allowed significant trade to develop across the DMZ, also on favorable terms to the North Koreans. So, over its history, North Korea has been nothing of the “hermit” kingdom cited in the media. The only major trading economy that has not had periods of significant trade with North Korea is the United States, which had always imposed a strict tariff regime on the non-market compliant country and has kept in place Korean War-era financial sanctions.

Remarkably, despite North Korea’s growth in trade, it is difficult to find a single year in which it did not import more than it exported. The persistent trade deficit, which by now adds up to hundreds of billions of dollars, was financed by foreign aid and unrepaid foreign credits and bank loans, which is far from self-reliance. These imbalances harmed the country’s once vibrant export industry, and are arguably more attributable to the lenders and aid givers than the North Korean recipients. Except for coking coal needed for the country’s large metallurgical and chemical industries, and petroleum, the country is rich in mineral and metal deposits, uranium, anthracite, and rare earths. It holds world-class reserves of high valued non-ferrous metals, zinc and lead; and it has ample, developed, hydropower resources. Investment fostered by the planned economy through the 1980s, trading away consumption and living standards in the interest of capital stock building and the military, created a large indigenous machinery and equipment sector and a strong workforce suited to manufacturing and industry.

North Korea can now produce a little of about everything it needs, making Pyongyang boast of self-reliance, while giving the appearance of an economy impervious to foreign sanctions. Its nuclear weapons and missile industries are the prime examples. North Korea probably needs to import very few parts for its one-of-a-kind nuclear-armed ballistic missiles. New observations about the indigenous production of its new ICBM TELS, are a good example, and should not be a surprise. But poor use of economies of scale due to the limited market, and spreading talent and capital across far too many products, means that qualities of these products remain less than adequate, and quantities are sparse relative to the 24 million population. Opportunity costs are, indeed, extremely high.

Many observers point to the collapse of the Soviet trading system as responsible for today’s weak trade linkages and emphasis on self-reliance. The command economy still uses a centralized bureaucracy to make key production and investment decisions utilizing fixed prices and rationing to distribute goods and services. Money is not even needed except to trade with the other, perhaps half, of the economy that is no longer socialized, and with the rest of the world. When this fixed price system interacts with either the domestic or foreign market price systems—where prices, wages, and interest rates adjust to changing supply and demand conditions—confused signals and inefficiencies occur. So, if Pyongyang wants to maintain its command economy in a world without its equivalents, it cannot trade normally with anyone, except by barter or by accepting international (market) prices and subsidizing or taxing domestic industry as appropriate. This has proven to be impossible in every state that has tried it, including North Korea.

Ironically, therefore, given the need to isolate the command economy’s fixed prices from international, market-determined prices, conservative officials probably like foreign-imposed sanctions. They do the work that the nation’s corrupt border patrols can no longer do. For example, the Party price commission has set electricity prices and prices for coal needed by power plants close to zero (although this may be about to change) to encourage heavy, electric intensive industry. But in present-day North Korea, a coal mine that can’t feed its miners—since miners need grain procured at high prices in markets—is tempted to sell its coal at $50 a ton to Chinese merchants rather than ship it, virtually free, to the power plant. The power plant is thus unable to produce electricity and state industry, sometimes even the coal mine, that depends on it suffers. Other factories also then resort to market activities to make ends meet and the system falls apart. But foreign sanctions against North Korean coal may force the coal back into the plan mechanism and back to the power plants. Anecdotal reports suggest that with sanctions, the electric power situation has improved because there is now plenty of coal. If history is any guide, however, movement backwards toward the fixed price system will again cripple productivity of labor and capital and new failures will occur—the miners will not be able to afford to eat. Indeed, another famine becomes likely as Pyongyang roles the dice on the peninsula’s variable climate.

Lessons:

- North Korea’s economy is more vulnerable to sanctions than it believes, but its policy choices are less influenced by economic efficiency than perhaps any other country. Its comparative advantages lie in metals and minerals and many types of less sophisticated machinery, and probably textiles, while its comparative disadvantages lie importantly in petroleum, coking coal, farming, medicines, and many consumer goods.

- Most vulnerable is the untested financial system, which has evolved quickly to include a partially dollarized (USD and RMB) monetary system and many informal lenders. Kim Jong-un has done well to keep the exchange rate and prices stable during his tenure, but how long can this last? A break in the won would be much more destabilizing now than in the past, when the planned system dominated, and money was relatively unimportant. Anecdotal reports indicate that loan-sharking, unheard of in a socialist economy, is already rampant and causing serious trouble.8

- Sanctions now touch most North Korean production for export. If they are relaxed at some point, efforts might be made to reward market-related companies—easily identified since they pay market wages—and not state enterprises, which use the ration system. This would be resisted by orthodox North Korean officials but welcomed by the growing numbers of officials and certainly the merchant class, who make the bulk of their living in market sectors. We have no indication that Kim himself is an orthodox communist.

- Petroleum is North Korea’s largest supply vulnerability. Sanctions, and lack of funds, are cutting into imports of refined products but crude oil is apparently still delivered to the state economy for free from China through a short pipeline. Beijing seems to hide this fact from the Chinese public, perhaps embarrassed by the support it provides to the increasingly unpopular dictator. Ending the free supply would put a critical dent in the command economy system since crude oil is allocated by the plan and not the market. Amid possibilities of adopting market pricing of electricity, paying for oil could cripple the state’s heavy industry while boosting efficiency in how energy is used in the private sector.

- While North Korea is about self-sufficient in grain, a bad harvest, which comes every five or ten years, would be devastating without large-scale imports. How to deal with famine ahead of time must be given attention by the international community. Aid given through the state ration system to cities, as in the past, is damaging to markets, but the likely alternative would be widespread death, as in 1995-97. Ideally, sanctions could be loosened on inputs for private farming and hardened on state farms and collectives, which produce inefficiently. Intense engagement will be required to make sure that the state does not use aid to support rations and crush markets, as before.

- Sanctions on North Korean textiles, a large, labor-intensive industry, may do significant damage to North Korean labor and to smaller-scale market-oriented factories. Much depends on whether the state textile mills, for example the huge Pyongyang Textile Mill, or private, foreign-managed plants are most affected. Sanctions that target only state firms—those that pay rations instead of real money—could be effective in shifting the economy towards the market and away from socialism.

Myth two: absence of US leverage

US administrations have continually sought “ever tougher” sanctions but gloss over the fact that the United States has never had significant commercial relations with North Korea, which has had little to do with sanctions. Most impactful has been its tariff treatment of any North Korean export items.Since the development of the postwar trading system, the United States has dramatically cut tariffs with all countries that have reasonably working market systems—as defined by their membership and adherence to WTO rules—but maintained extremely high tariffs on non-market economies, given the difference in pricing systems. North Korea has made no movement toward joining the WTO, so prohibitive tariffs on its exports, much higher than on just about any other country, continue. Pyongyang can complain of unfair treatment, but it is entirely due to its own decision not to join the international trading system. Still, prohibiting trade that is not happening anyway will not incur much difference.

Recognizing this lack of leverage on direct trade, the United States has tried to take advantage of the dominance of the US dollar and banks in global financial system to make it difficult for North Korea to engage in third-party trade. Currently it is trying, as with the Executive Order 13810, to apply “secondary sanctions” on third-country firms and nationals that do business with North Korea. This has had some impact but risks damaging US financial interests all over the world. Moreover, the logic is complicated. If China, for example, was effectively abiding by current UN sanctions, a secondary action against a Chinese bank in Dandong, as was recently applied, should not be needed. And if China is not complying, no amount of US financial actions can stop Chinese-North Korean linkages and the issue would be moot.

Still, the idea that the United States lacks leverage is incorrect. By effectively prohibiting exports from North Korea to the United States, third party firms that otherwise might want to invest in North Korea will not, choosing instead a country with easy access to the US market. The result has been a failure of North Korean attempts to bring in foreign investment, as in its highly touted special trade zones announced a few years ago. The now defunct Kaesong Industrial Zone along the DMZ was one such project, stymied in part because the United States refused to grant low tariffs on imports from South Korea to goods produced in that zone. Similarly, Chinese firms that import North Korean textiles and try to export finished products to the United States must do so illegally, by hiding their true origin. US leverage is very powerful, but latent; if North Korea decides to change its nuclear and economic policies, one could expect a huge and immediate positive impact on the North Korean economy. A nuclear weapons resolution by itself, however, would not solve the problem even if all the post 2006 sanctions were removed. Effective market reforms that would lead Pyongyang into the WTO will also be necessary.

Lessons:

- US leverage is not in current transactions, since there are so few, but in what can only be described as an enormous opportunity cost for the Kim regime. More importantly for North Korea, foreign direct investment from third countries is unlikely as long as the US market is unavailable. And the United States effectively controls entry into the WTO.

- The potential is limited not just by sanctions. More fundamentally, North Korea’s absence from the WTO system means the United States automatically imposes prohibitive tariffs on most of its products. For sanction relief, tariff reductions and systemic change should come hand-in-hand.

- North Korea did not take advantage of the US lifting of the Terrorist List and TWEA in 2008 to apply to the WTO. With those sanctions now re-imposed, US law requires any such application to be automatically vetoed. North Korean entry into the WTO, and its acceptance of the market economy, would have huge positive implications for all concerned, so the United States needs to be ready to change the ruling again.

Myth three: China is helping North Korean stability

North Korea may actually be becoming less stable, at least from Beijing’s perspective. China has been a primary source of frustration to international efforts to halt North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, as shown by its rise in trade during the early years of the sanctions. Most do not doubt the Chinese dislike of Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons, but their removal cannot come at a cost to Chinese security. Such security threats include: a probable flood of North Korean refugees, especially given the large number of Korean Chinese who live along the border; another Korean war in which China becomes embroiled; the likely presence of US troops on the Yalu River; and the unpredictable chaos inside an important, fellow socialist, neighbor. Since most sanctions directly impact Chinese businesses as well as North Korean ones, local economic costs also are important. To combat these worries Beijing (and Moscow) until a year ago inserted caveats in the sanctions to prevent harm to the livelihood of North Korean civilians. (See table two above). Everyone knew this loophole would take much pressure off of Pyongyang.

The situation has changed substantially, however, with the November 2016 and August and September 2017 sanctions, although how well Beijing will enforce these, and for how long, is open to question. Beijing must stop importing coal, ferrous and non-ferrous ores and metals, textiles, and fish products, which together totaled $2.3 billion of its $2.6 billion in imports from North Korea in 2016, and cut refined petroleum product sales.9 Additionally, joint ventures with North Korean firms in China and in North Korea are being eliminated and North Korean contract workers in China are being sent home. This, on paper, is close to a complete break in economic relations—about the only thing not yet touched is China’s provision of crude oil, thought to be about 500,000 tons a year delivered at no cost based on an ages-old aid agreement and Chinese sales of normal goods to North Korea.

Clearly these new sanctions reflect a change in Beijing’s calculation of its security interests, likely influenced by developments on three fronts. First is the dramatic improvement in North Korean nuclear and missile tests. Beijing has long undervalued its capabilities, at least in public, and now, somewhat embarrassed, may be playing catch up. Secondly, North Korea may already be looking unsteady to Beijing, given Kim’s execution of maternal uncle Chang Song-taek and step-brother Kim Jong-nam, both of whom were considered close confidants to China. Beijing may now be thinking major changes need to take place for the country to remain a steady partner. Third, the rising US and Japanese bellicosity raises fears of military action which Beijing fears would plunge the whole region into chaos.

China’s change in tactics, however, should not be thought of as giving up on North Korea. Most likely, it thinks a higher level of pressure on Pyongyang will bring it to the table. It no doubt hopes the sanctions will be short-lived and may already be looking for ways to retreat from them as soon as possible.

Lessons:

- North Korea’s stability is still China’s key concern, but the source of perceived instability may be shifting from external factors to problems within the Kim regime, essentially a distrust of Kim’s capacity to effectively rule the country in a way beneficial to China. For the United States to continue to gain Chinese assistance, stability issues must be at the forefront, with policies to create a more, not less, stable Korean Peninsula—one that does not threaten Chinese economic or security interests.

- The new sanctions are tough, perhaps too tough to be believed. The only big, new step China can take is to cut off crude oil supplies, or at least make Pyongyang pay for it, which for decades has been provided as aid. China may be saving that for one of its last big sticks.

- Sanctions that harm civilian livelihood, especially those on textiles, are now being tolerated by Beijing, though perhaps not for long. China is more likely willing to use sanctions as tools, turning them on and off, depending on Pyongyang’s reactions. This can be helpful, but Pyongyang has worked covertly on its nuclear and missile programs, even when it appeared to cooperate. How well China has understood that is not well known. Intelligence sharing is thus important.

- Chinese businesses are key drivers of reform in North Korea, since they engage directly with North Korea’s entrepreneurs, whereas the Chinese government provides aid to Pyongyang. They should be dealt with as cooperatively as possible.

Myth four: Nuclear weapons give Pyongyang security

What country would “give away” something as important as its foreign or domestic security? Why would any country trade away something it sees as necessary for its own survival? One can make a case, as Pyongyang does persistently, that facing a nuclear-armed superpower that wants to destroy it, it has no choice but to build nuclear weapons for deterrence. This begs the question, however, are nuclear weapons really doing their job? Is the regime more secure with them now then it was years ago, without them? And if not now, will the regime be more secure after such weaponry is fully developed and deployed?

Three generations of North Korean leadership have adopted the nuclear security banner and, despite negotiations that may have slowed their development, maintained this program. Large risks were taken and tremendous resources employed. The program is now, by all appearances, nearing a successful completion. Ironically, the program’s successes over the past thirty-plus years also can be measured against the steady downward trend in the country’s economy and a near collapse in its socialist system, a trend that has taken its per-capita income from near parity with South Korea to near 1/40th of that level. Nuclear issues of course are not the only or even the most important causes of this calamity but without participating in the global economy, more disasters, such as famine and financial crisis, are inevitable.

Lessons:

- For sanctions to work, they need to make Kim believe the country, or more importantly, his regime, is safer without nuclear weapons than it is with them. Regime safety has two components, external and internal. Arguably, nuclear weapons, once deployed, do provide some safety from external attack, so if this is the regime’s main security concern, the weapons make sense. But if the major threats are considered to be internal, and grave enough to threaten Kim Il-sung’s eldest son, everything can change.

- To be effective in changing North Korea’s threat calculus, sanctions must threaten the internal stability of the regime. With China and Russia now at least partially on board, this may be possible. Most helpful is to illustrate that by placing such high priority on nuclear weapons, Pyongyang has weakened its control over workers and property. The condition of state enterprises, infrastructure, and the conventional military are dire, and the state provided wages of millions of government workers are so small that most survive by engaging the market. Decentralized market forces now threaten aspects of the command economy system but not yet the state itself. Which side of this equation will sanctions be on?

- Kim needs to be persuaded that instead of buying security against foreign threats, nuclear weapons and their accompanying foreign-imposed sanctions are only increasing the threat of domestic instability. Sanctions, smartly employed, can do that.

| UN Sanctions Against North Korea: 2006-2017 | |||

| Resolution | Date | Cause | Sanctions (selected items) |

| S/RES/1695 | 15 July 2006 | Ballistic Missiles | Bans trade related to missile and nuclear production and exports of luxury goods to North Korea. |

| S/RES/1718 | 14 October 2006 | Nuclear Test | Bans trade in most military items; limited travel and civilian trade bans. |

| S/RES/1874 | 12 June 2009 | Nuclear Test | Bans military trade; bans finance and trade except for humanitarian and development purposes. |

| S/RES/2087 | 22 January 2013 | Missile Test | Enhanced monitoring, no sale or finance of items helpful to nuclear or missile program—specifies sanctions are not to harm North Korean livelihood. |

| S/RES/2094 | 7 March 2013 | Nuclear Test | Urges targeted financial sanctions, adds sanctioned individuals and companies, halts bulk cash transfers to NK, tightens monitoring. |

| S/RES/2270 | 2 March 2016 | Nuclear and Missile Tests | Restricts imports from North Korea of coal, iron ore, rare earths and other items except when livelihood is at stake, and prohibits export of aviation fuels. |

| S/RES/2321 | 30 November 2016 | Nuclear Test | Sets limits on coal imports from North Korea of $54 million or 1 million tons in third quarter of 2016, whichever is lower, and $401 million dollars or 7.5 million tons in 2017. Bans imports of iron, iron ore, except when livelihood is at stake. Bans imports of copper, nickel, silver, zinc, seafood, lead, lead ore. Prohibits new joint ventures or expansion of existing ones. Bans expansion of North Korean workers overseas. Regrets economic hardships imposed on people by the North Korean government. |

| S/RES/2371 | 5 August 2017 | Missile Test | All coal and iron ore imports from North Korea are banned, except transfers of coal that originated elsewhere. (i.e.) it removes limits and allowances for livelihood considerations expressed in 30 November resolution and removes “by aircraft or shipping vessels”, thus including imports by rail or truck. “Reaffirms that the measures imposed are not intended to have adverse humanitarian consequences for the civilian population of the DPRK or to affect negatively or restrict those activities” thus allowing case by case exemptions. Adds to individual sanctions. |

| S/RES/2375 | 11 September 2017 | Nuclear Test | Bans imports of textiles from North Korea, prohibits an increase in crude oil exports to North Korea and cuts petroleum product exports to 500,000 tons in fourth quarter 2017 and 2 million barrels a year, thereafter, subject to humanitarian concerns. Further restricts overseas labor. |

| US Executive Orders Against North Korea | ||

| Executive Order | Date | Key actions |

| 13466 | 26 June 2008 | President Bush removes North Korea from the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) and Terrorist List (TL) but in this EO re-imposes most sanctions that had been covered by TWEA and TL so there is little net effect. Importantly, however, TWEA had required the US to veto North Korean participation in WTO, IMF, World Bank thus North Korea is able to apply without certain knowledge of a US veto |

| 13551 | 30 August 2010 | Adds designated individuals and organizations |

| 13570 | 18 April 2011 | Adds UN 1718 and UN 1874 sanctions on imports from NK and adds designated individuals and organizations |

| 13687 | 2 January 2015 | Expands 13570 and adds to list of designated North Korean persons and organizations |

| 13722 | 15 March 2016 | Ensures implementation of UNSCR 2270, strengthened export and import restrictions, blocks North Korean government and party transactions and assets, prohibits new investment in NK. Provides authorities for Treasury to block funds transiting accounts linked to NK and to sanction foreign financial institutions that knowingly facilitate transactions with North Korea. Blocks ships from US entry if they have called on a NK port within 180 days |

| 13810 | 20 September 2017 | Provides authorities for US agencies to sanction foreign individuals and institutions that knowingly engage with an expanded list of North Korean industries and organizations. (secondary sanctions) |

1. November 2017 data, Global Trade Atlas.

2. NCNK Issue Brief, The National Committee on North Korea, https://www.ncnk.org/sites/default/files/NCNK_Issue_Brief_Statistics_December_2009.pdf

3. North Korea, Country Data, http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-9580.html

4. Trade is highly seasonal, so it is displayed here as a twelve-month running total, (the last data points are cumulative November 2016-October 2017 data) giving a longer view of trade trends. Additionally, China’s reported crude oil exports, likely about $300 million over each 12-month period, are excluded due to a break in Chinese reporting beginning in January 2014.

5. “Market Trends,” Daily NK, http://www.dailynk.com/english/market.php

6. Kang Mi-jin, “Authorities push tax on electricity generated by household solar panels,” Daily NK, November 22, 2017, http://www.dailynk.com/english/read.php?num=14846&cataId=nk01500

7. Ruediger Frank, “Economic Sanctions and the Nuclear Issue: Lessons From North Korean Trade,” 38 North, September 18, 2017, http://www.38north.org/2017/09/rfrank091817/; William Brown “Can sanctions get a Mulligan?” 38 North, October 6, 2017, http://www.38north.org/2017/10/wbrown100617/

8. Kang Mi-jin, “Loan sharks resorting to violence to collect debts,” Daily NK, November 29, 2017, http://www.dailynk.com/english/read.php?num=14861&cataId=nk01500

9. Global Trade Atlas, November 2017 data

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn