The year 2017 brought unusual dynamism all around the world and particularly related to the Korean Peninsula. In the United States, an unprecedented type of president was inaugurated with scant appreciation of alliances and apparent lack of knowledge of the relations between the United States and South Korea, bringing an unfamiliar and wary air to the region. In China, President Xi began his second term, expressing ambition for an elevated status of China on the global stage. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo also solidified his political base in Japan by winning an early election to secure his political standing and his party’s future. North Korea conducted more than ten missile tests and its sixth nuclear test, claiming that it had completed its nuclear program. In South Korea, one president was impeached and ousted, and a new one was elected much earlier than scheduled. It was remarkable not only because of the unexpected but peaceful transition of power, but also because it signified a far-reaching transition from conservative to progressive government.

As the South Korean electorate decisively chose Moon Jae-in as president, concerns loomed in diplomatic circles in Washington DC. Recalling rocky relations under progressive president Roh Moo-hyun, pundits cast doubt on the future relationship between the two countries. Some said that uncomfortable elements inherently operate when a conservative US government and a progressive government in South Korea have to work together.

The situation was, however, quite complicated. While the new US president was not very appreciative of South Korea, the North Korean threat and tension in the region were being escalated more than ever before. China had been wooing South Korea for the past few years, but now the country was economically retaliating against Seoul for its decision to deploy the THAAD system. Moon Jae-in inherited all the foreign policy burdens from the previous Park government, which was ousted by the South Korean people at the most difficult time.

This article examines how the South Korean public perceives the current situation and thinks about military options. It explores which country South Koreans consider the most important and cooperative security partner under these difficult circumstances. It finds that, for many, the United States remains a strong and reliable ally and cooperative military partner, decoupling it from Trump. Although Trump was quite unpopular among South Koreans, his reputation has not hurt the overall importance of the United States as an ally. China, on the other hand, seems to have used up its political capital due to the THAAD issue. The whole THAAD drama apparently reminded many South Koreans that the country had not truly been on South Korea’s side and could take sides with North Korea in the event of an inter-Korean conflict. As North Korea’s provocations continued, the public visibly moved toward the hardline front, supporting THAAD deployment and tactical nuclear weapons as well.

The United States, the Most Important Ally

The most serious concern regarding security on the Korean Peninsula is coordination between the new governments of South Korea and the United States. The concern probably stems from the past experience of a progressive government under Roh Moo-hyun and a conservative government under George W. Bush. Roh, who was elected in 2002 and died tragically in 2009 after leaving office, reportedly did not have good relations with Bush. As a dissident of the democratization movement, Roh was a nationalistic figure who became famous for having asked what was wrong with being anti-America. The statement resonated with the public because the tragic death of two junior high school girls by an armored US vehicle in 2002 had generated a spike in anti-American sentiment in the country.

It, however, does not represent all of his American policies. Despite his somewhat provocative comments, he sent South Korean troops to Iraq, visited the United States first once inaugurated, and even worked very hard to complete the KORUS FTA deal. Nonetheless, a number of DC pundits in diplomatic circles seemed to remember the rocky relations with South Korea under Roh. Attentive to the Moon government’s American policy, they wondered whether the bilateral relationship would remain as strong as it had been for the past nine years under conservative governments. It was partly because Moon was a high ranking official and a friend of Roh, and partly because there is an escalating nuclear threat from North Korea. This time, the threat was not just a nuclear test—for a weapon that could be used in the East Asia region—but an ICBM, which the North argues could reach the continental United States.

The situation has changed tremendously in 15 years. Unlike in 2002 when anti-Americanism swept the whole country, the United States has overwhelmingly been valued as the most important ally to South Korea in recent days. This is because of several significant military provocations by North Korea, and also because of much improved relations between the two countries and heads of state. President Obama’s popularity played a significant role in improving the public image of the United States among South Koreans. For the past at least five years, the United States has been the most popular, the most important, and the most trusted neighboring country according to Asan surveys.

The good days for the relationship between South Korea and the United States appeared at risk when Trump was elected president. He publicly called South Korea a “free-rider” for not paying enough for the stationing of US troops on the peninsula. Also, he criticized harshly the KORUS FTA as a “disaster” and claimed that he would renegotiate the agreement once he had been elected. Trump, for many obvious reasons, was not very popular among the South Korean public. Some worried that his low popularity might affect South Koreans’ sentiments toward the United States and the ROK-US alliance.

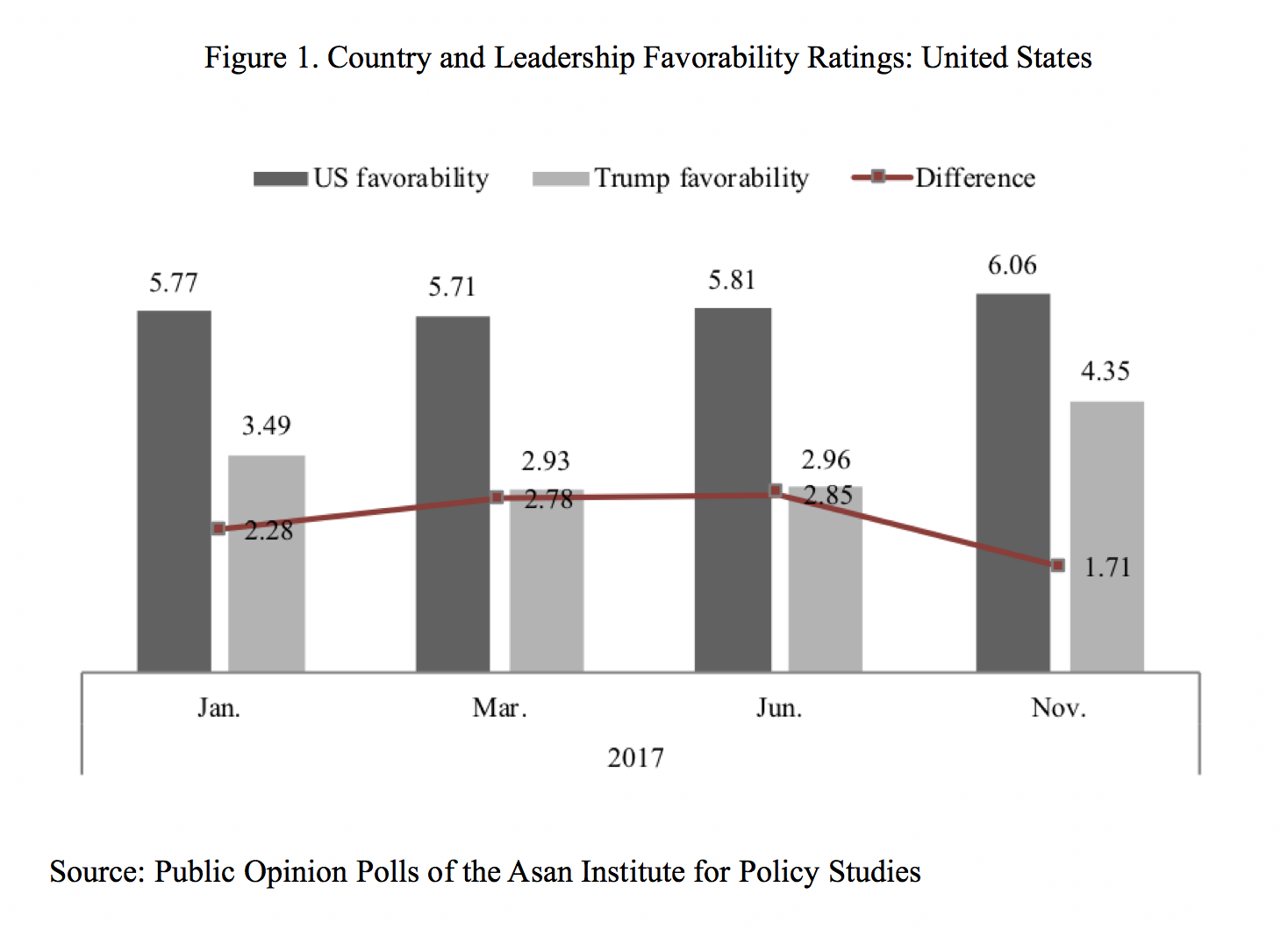

Figure 1 indicates that the United States’ and US president’s favorability scores have shifted over time. Interestingly, US favorability in South Korea is not influenced by the American president very much. The favorability score is measured on a scale of zero to ten (dislike very much – 0, like very much – 10), and the US scores were around 5.7 in the first half of 2017. This is slightly lower than what the United States had usually scored under the Obama presidency, e.g., in 2016, the last year of his administration, the average favorability score for the United States was 5.99. The Obama administration maintained a good public image and scored over 6 many times. Trump’s favorability ratings, which were measured in the same way as the country ratings, have been amazingly low for an American president. His score was lowest when he was a presidential candidate of the Republican Party in 2016. Surrounded by numerous scandals and due to his harsh and vulgar rhetoric, his favorability score was around 1. Obama, on the other hand, even scored higher than 7 just before he left the White House. Trump’s favorability score went up to and stayed around point 3 after he was elected and inaugurated. Nevertheless, it is still low compared with his predecessor.

The difference in favorability scores for Trump and the United States remained quite steady over the year. Trump’s score went up some in the November survey, but it was mainly due to the reasonable and relatively calm posture he showed during his state visit to South Korea early in November. It is undeniable that he is not a typical American president.

Sentiment toward the United States moved separately. The situation was perceived to be quite serious by South Koreans due to continuous military provocations by North Korea. As the North conducted several missile tests and the sixth nuclear test in 2017, South Koreans wanted a stronger military alliance with the United States than ever before. This necessity naturally made them feel close to the United States. Being pragmatic, South Koreans decoupled how they view the United States and its president. How long this type of decoupling between the United States and Trump will last is not clear. Yet, if his rhetoric begins to be realized in his policy and South Korean interests are hurt, this could affect people’s sentiments toward the United States. So far, it has not yet had any significant effect.

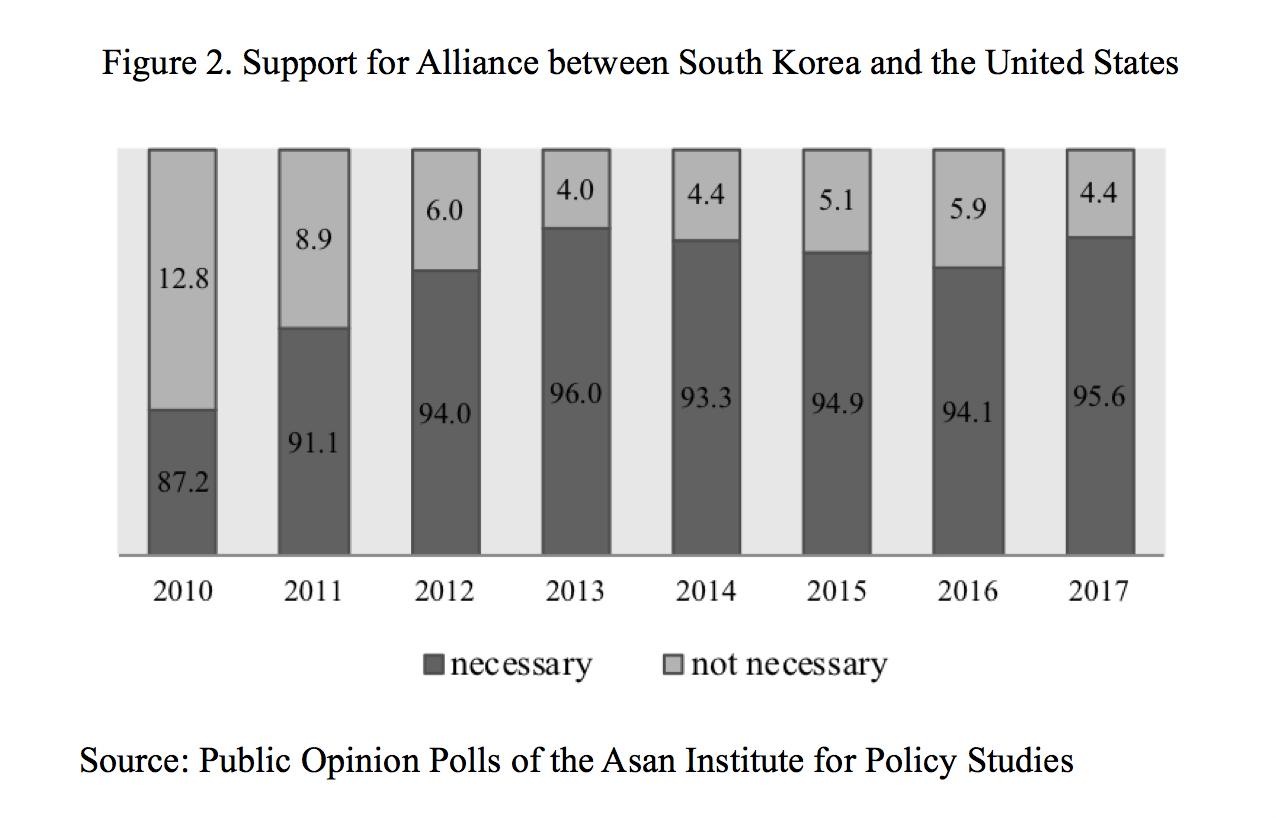

As expected, people’s support for the ROK-US alliance is very strong. According to the annual survey conducted by the Asan Institute in 2017, 95.6 percent of respondents answered that they thought the ROK-US alliance was necessary. The differences across generations, ideological stance, and party affiliation were all minimal on this question. In fact, the number had increased by 1.5 percentage points from answers to the same question in 2016. And it is the second highest rating following 96 percent in 2013. Although small, the increase reflects the seriousness of the situation in the eyes of many South Koreans, and their attitude toward the alliance has not changed at all. Multiple missile tests and the sixth nuclear test in 2017 caused severe tension on the Korean Peninsula, and people relied on military deterrence provided by the United States.

South Koreans still strongly support the ROK-US alliance despite what many see as Trump’s harsh, sometimes reckless, and personalized denunciations of North Korea, which heightened tensions further in the region, worsening the situation. South Koreans are used to hearing provocative rhetoric and unanticipated reactions from the North, but not from the president of the United States. Some of the current American president’s words were not just critical but also insulting to South Korea. However, the South Korean people separated his harsh rhetoric from practical military needs at the moment. Regardless of Trump’s tweets, South Koreans thought that the alliance is very important in the face of the North Korean threat.

Recognition of the necessity of the ROK-US alliance is shared across diverse demographic groups. Conventionally, those in their 40s are considered to be the most progressive and least attracted to the United States. Nonetheless, 90 percent of them were also supportive of the alliance. The young generation, who are known to be conservative on security issues, is as strongly supportive as the old generation regarding the alliance. Even the Justice Party supporters who are the most progressive in the South Korean partisan landscape express strong support for the alliance.

Overall, South Koreans’ perceptions of the United States as important ally have solidified even more over the year. Trump was not popular, but how people think about him did not matter for evaluation of the alliance. As North Korea’s nuclear threat intensifies, South Koreans feel more strongly the importance of the United States as an ally. North Korea’s relentless missile tests and nuclear test made people become practical on security issues.

Table 1. Support for ROK-US Alliance by Demographic Group

| Not Necessary | Necessary | ||

| Age | 20s | 3.8 | 96.2 |

| 30s | 4.7 | 95.3 | |

| 40s | 7.7 | 92.3 | |

| 50s | 3.8 | 96.2 | |

| 60s or over | 2.4 | 97.6 | |

| Ideology | Conservative | 2.4 | 97.6 |

| Moderate | 3.5 | 96.5 | |

| Progressive | 9.6 | 90.4 | |

| Party Affiliation | Minjoo Party of Korea | 6.8 | 93.2 |

| Liberal Korea Party | .6 | 99.4 | |

| People’s Party | 4.7 | 95.3 | |

| Bareun Party | 3.3 | 96.7 | |

| Justice Party | 7.3 | 92.7 | |

| No Party Affiliation | 2.0 | 98.0 |

Source: Annual Asan Survey, 2017.

China and the Missing Orbit

Park Geun-hye, in the first half of her term, was very friendly to China. Criticisms arose in Washington and Tokyo that Seoul was getting too close to Beijing, and some even worried that South Korea was going into the Chinese orbit. In contrast, South Korean views of Japan were viewed with suspicion in Washington and Tokyo. Wendy Sherman, former undersecretary in the State Department, stated, “nationalist feelings can still be exploited, and it’s not hard for a political leader anywhere to earn cheap applause by vilifying a former enemy.” She then lamented, “to what extent does the past limit future possibilities for cooperation? The conventional answer to that question, sadly, is a lot.”1 Her comments, provocative to many Koreans, appeared when relations between South Korea and Japan were at their low point. The tilt toward Beijing and away from Tokyo aroused concern in Washington.

This message was conveyed to the South Korean government, which had been taking a hardline stance to Japan when the United States strenuously pursued trilateral military cooperation in the region while improving relations with China. The presidents of South Korea and China exchanged state visits in 2014, and Park even observed the military parade in Beijing in 2015, where no other leader from the liberal world was in attendance. China was content, while the United States and Japan were obviously uncomfortable.

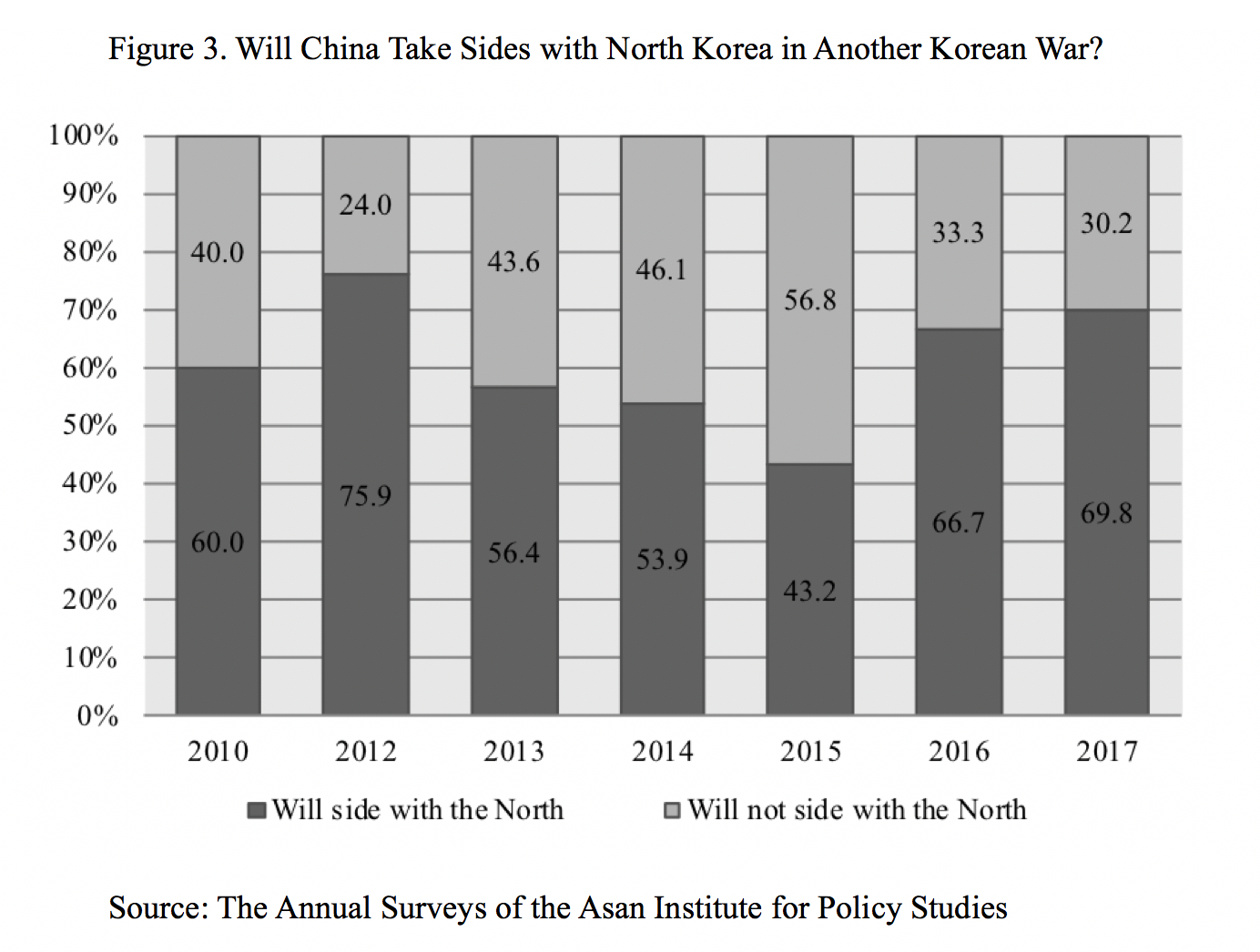

Indeed, Park put a great deal of effort into improving relations with China. Her personal relationship with Xi apparently helped. As a result, China earned a much better reputation among South Koreans than before and its favorability rating increased dramatically. The most visible example of this changed attitude of the South Korean public toward China is their expected position once the North and South had come into conflict. To most South Koreans, the United States was supposed to take the side of South Korea once there was another fraternal war between the two Koreas. There was almost no doubt about it. China, on the other hand, was largely considered to be on the North’s side. The memory of the Korean War where China fought against South Korea and the United States joining North Korea remains alive among many South Koreans. And, more importantly, China was still seen to be a communist country. A changed perspective could be seen emerging in 2013, 2014 and 2015.

As Figure 3 indicates, a disproportionate number of South Koreans, in general, believe that China would take the side of North Korea were another Korean war to break out. In 2010, 60 percent of South Koreans answered that China would take the side of North Korea in the case of a second fraternal war. The number had increased to 75.9 percent in 2012. This was a reflection of China’s stance toward the sinking of the Cheonan warship and the shelling of Yeonpyong Island, the two most significant and direct military attacks by North Korea. The mood had changed in 2013 when the new heads of state took office in both countries. Xi Jinping showed warmer gestures to South Korea, whereas he distanced himself from the North. Park also was not hesitant to show warmth toward China. As a consequence, South Koreans who thought China would take the side of North Korea decreased to 56.4 percent in 2013. In 2015, the proportion of the South Korean public who thought China would not take the side of North Korea was even higher than that of those who thought China would. 56.8 percent of South Korean respondent believed that China would not join the North Korean side when another war broke out, while 43.2 percent of them believed it would. It was a good year for the two countries’ relations, and people’s favorability score for China went up as well.

However, a reasonable doubt that China still would be on the North Korean side came to the fore in 2016. It was after the South Korean government announced that it would deploy the THAAD system on the peninsula. China reacted vehemently, and the proportion of respondents who believed that China would not take sides with North Korea decreased to 33.3 percent in 2016. In the following year of 2017, it was 30.2 percent. Those who believed that China would be with the North increased to 66.7 percent in 2016 and 69.8 percent in 2017.

The heyday between South Korea and China was gone once South Korea announced that it had decided to deploy the THAAD system in the southern part of the country. China had repeatedly asked about the THAAD issue previously, and the South Korean government had maintained the posture that nothing was determined. Once the announcement was made, Xi Jinping was reportedly furious. In 2017, China began to economically retaliate against South Korea. Chinese tourism to South Korea was technically banned, Korean artist performances in China were cancelled, and the “Korean wave” was practically ended in the country. South Korean retail companies were boycotted, and it seriously hurt South Korean industries— tourism, entertainment, and South Korean retail markets in China, just to name a few.

For instance, the number of tourists from China to South Korea in 2016 was about 8.3 million. In 2017, it was cut almost in half to 4.4 million tourists.2 The reduction in tourists cost the South Korean companies substantially; for instance, Amore-Pacific Cosmetic—which had been very popular and made huge profits in China—had its sales decline by 9 percent and profits by 30 percent. Other cosmetic companies saw profits hurt, too, including Innispris and Espoir.3 South Korean products and markets were boycotted, which hurt a number of South Korean retail companies that have branches in China.

As news of the Chinese retaliation against South Korea was reported, South Koreans became furious. They criticized the Chinese government. For South Koreans, THAAD was an unavoidable choice in the face of the continuous North Korean provocations and escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula. China being uncomfortable with THAAD deployed in South Korea was understandable to a certain degree, but many South Koreans believed that China should have done something to restrain North Korea if they so hated THAAD being deployed in South Korea. Even for those who did not approve of the deployment, China’s aggressive economic retaliation was negatively perceived. It was considered an unfair and unilateral assault by a superpower. In light of all these considerations, the numbers clearly indicate that South Koreans’ views of China had been damaged by the THAAD controversy, and they seem to have lost the trust in China, which had been building over time.

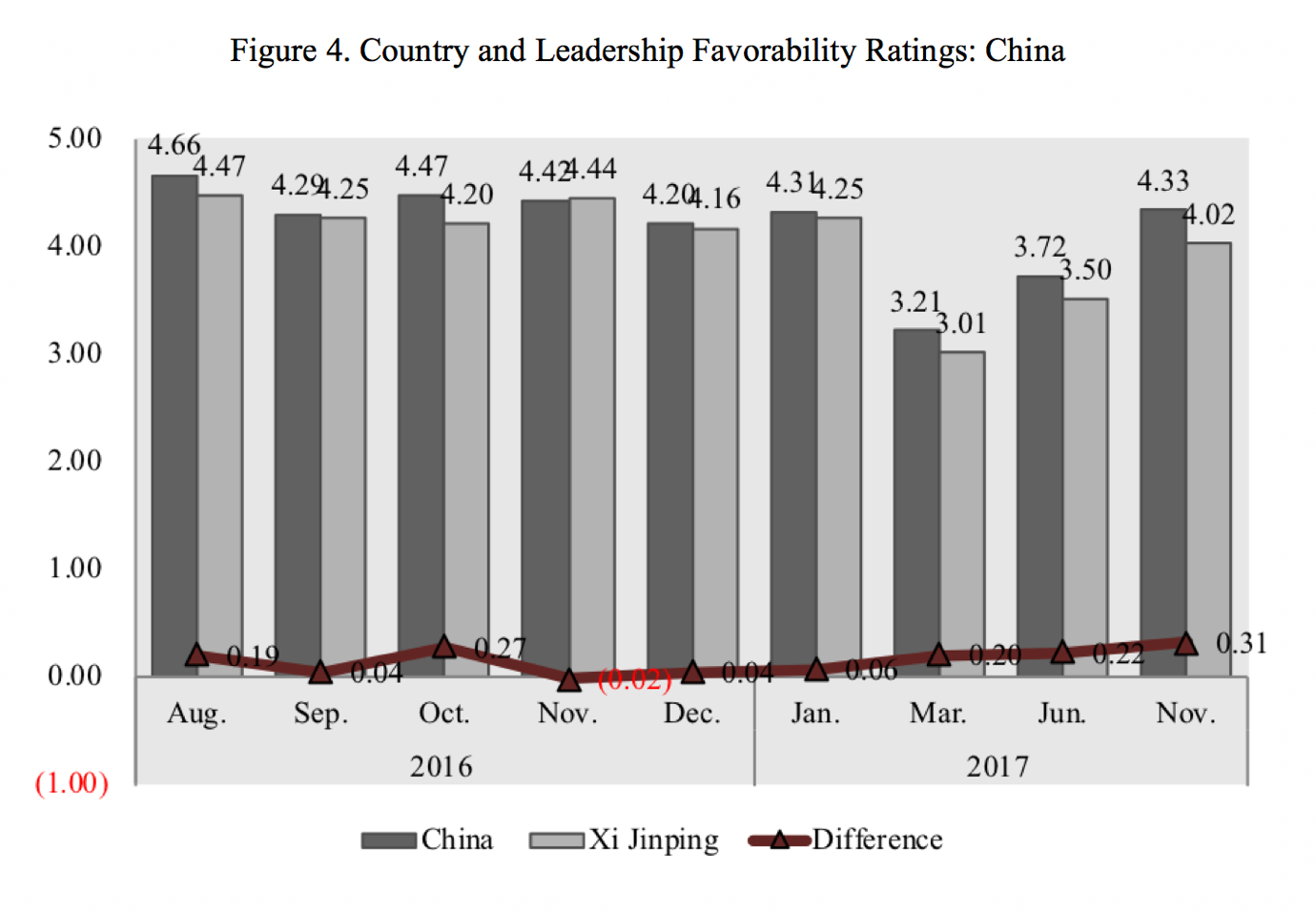

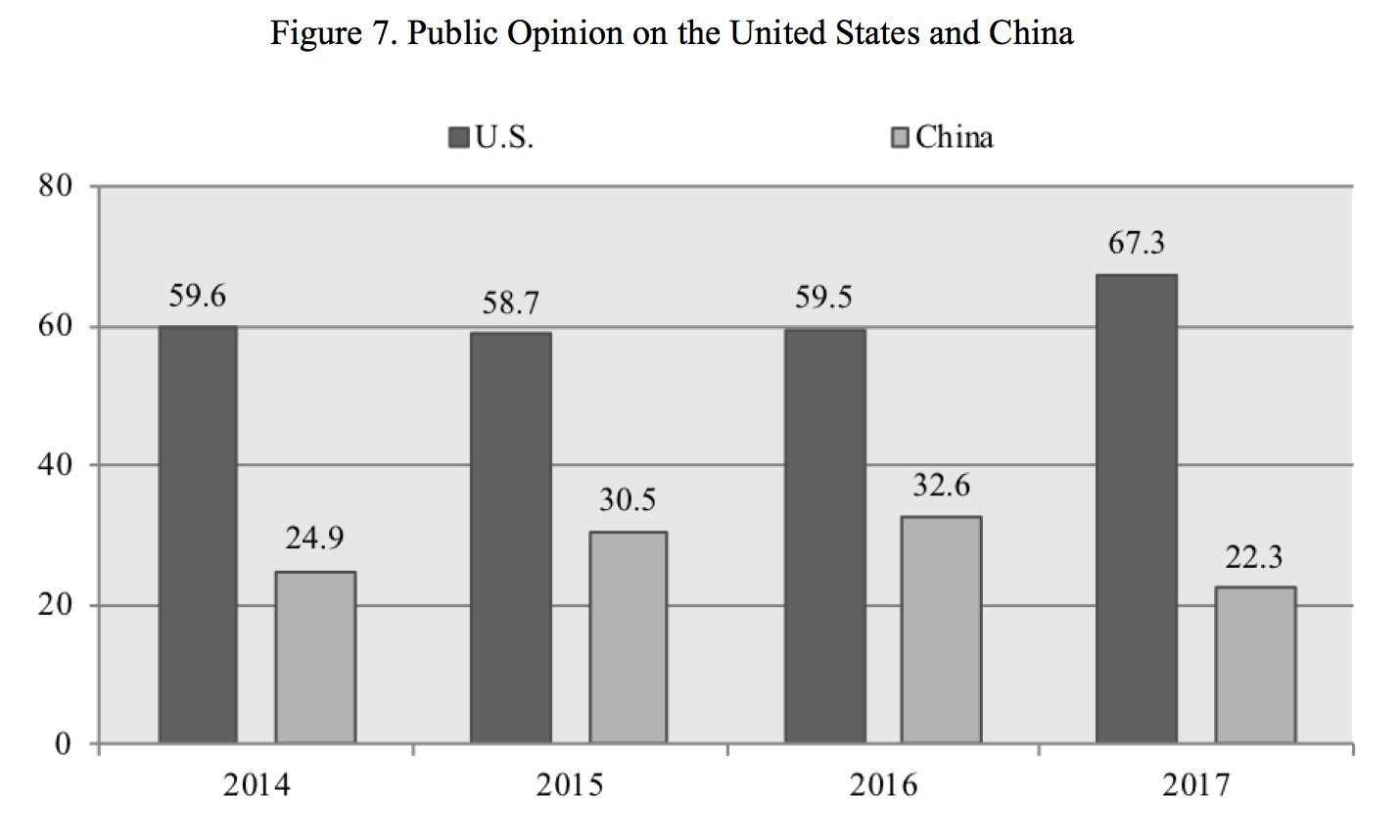

As anticipated, the public’s sentiment toward China and Xi Jinping was damaged. According to the Asan Institute’s polls conducted in March 2017, the Chinese favorability rating among South Koreans recorded its lowest score ever at 3.21. It was even lower than the Japanese favorability rating in the same period although the difference was not statistically significant. The result shocked many, since favorability ratings for Japan had almost always been lowest except for North Korea among South Koreans. Similarly, the favorability rating for Xi Jinping plummeted as well.

Once fallen, it does not seem to be very easy for China and Xi to recover the previous level of favorability. Even when South Korea had good relations with China, South Koreans had not fully trusted China, despite its stunning rise as the number one trading partner and partner in bilateral exchanges. Chinese travelers became the most important visitors for South Korea’s tourism industry. Nonetheless, there were differences which were not easily reconcilable between the two countries. A great number of South Koreans considered China a communist country, and only about 30 percent of South Koreans felt that Korea and China share the same values such as Confucianism. Premodern China, once the most important historical and cultural influence in the region, has long gone. Modern China after the impact of the Cultural Revolution is disconnected from that history and is what China represents today for many South Koreans. China is a country economically and militarily growing at an unprecedented rate. It is a country with a large population and vast land—a neighbor overwhelming for what it might become. The two countries’ relationship, therefore, is not as solid as the ROK-US alliance, which has endured for more than sixty years. Based on the shaky foundation and relatively low trust level, South Koreans turning against China when the THAAD issue came to the fore does not come as a surprise.

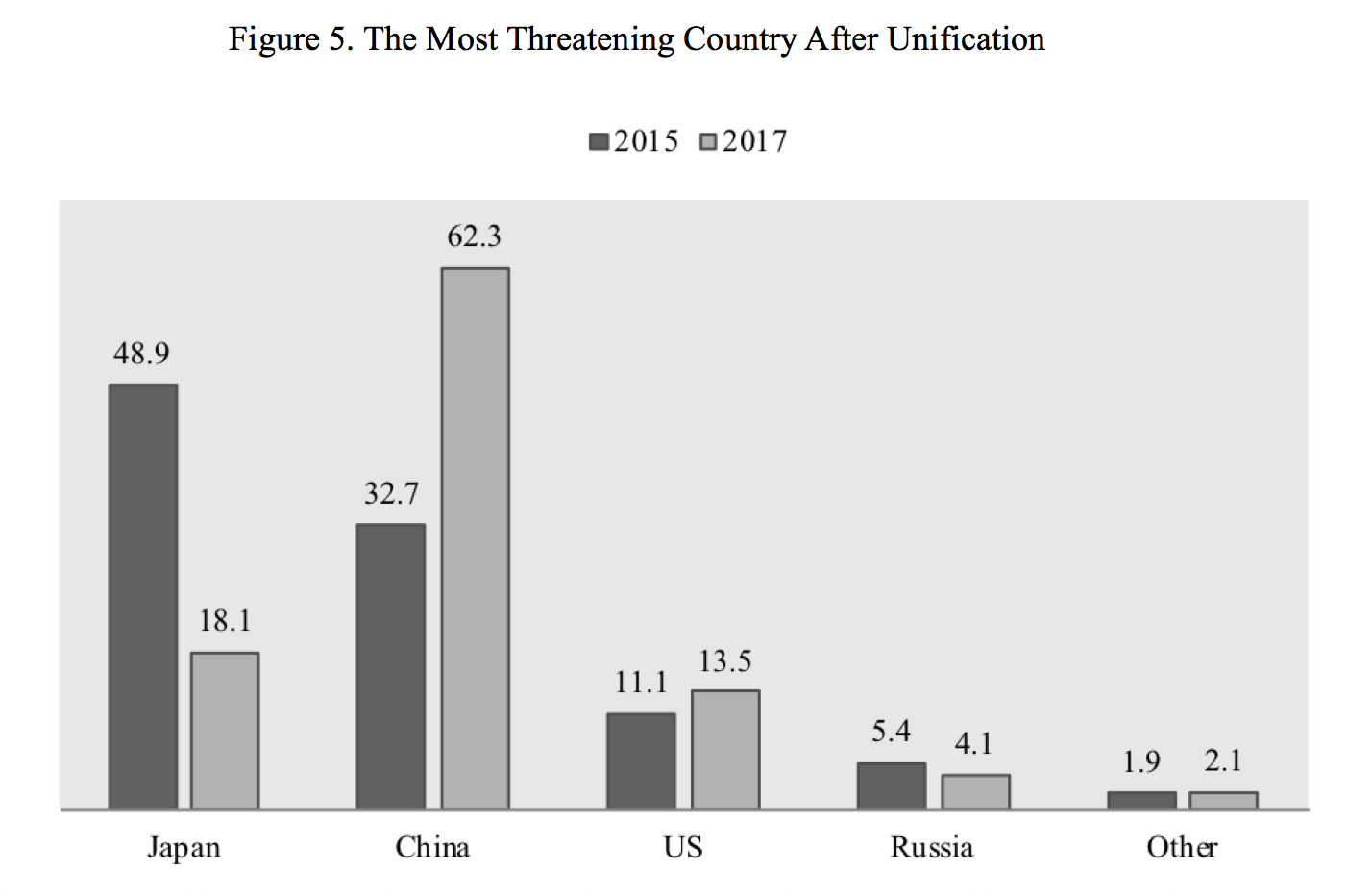

Another interesting question is how South Koreans answered when asked which country posed the most threat after unification with North Korea. In 2015, when China and South Korea maintained a good relationship, Japan was viewed as the most threatening at a rate of 48.9 percent followed by China with 32.7 percent. The numbers were dramatically changed in 2017. About 62 percent of respondents chose China as the most threatening country after unification. Those who chose Japan decreased to 18.1 percent. This may reflect the changed economic and military status of China; yet, the result demonstrates how differently South Koreans view China from just two years ago.

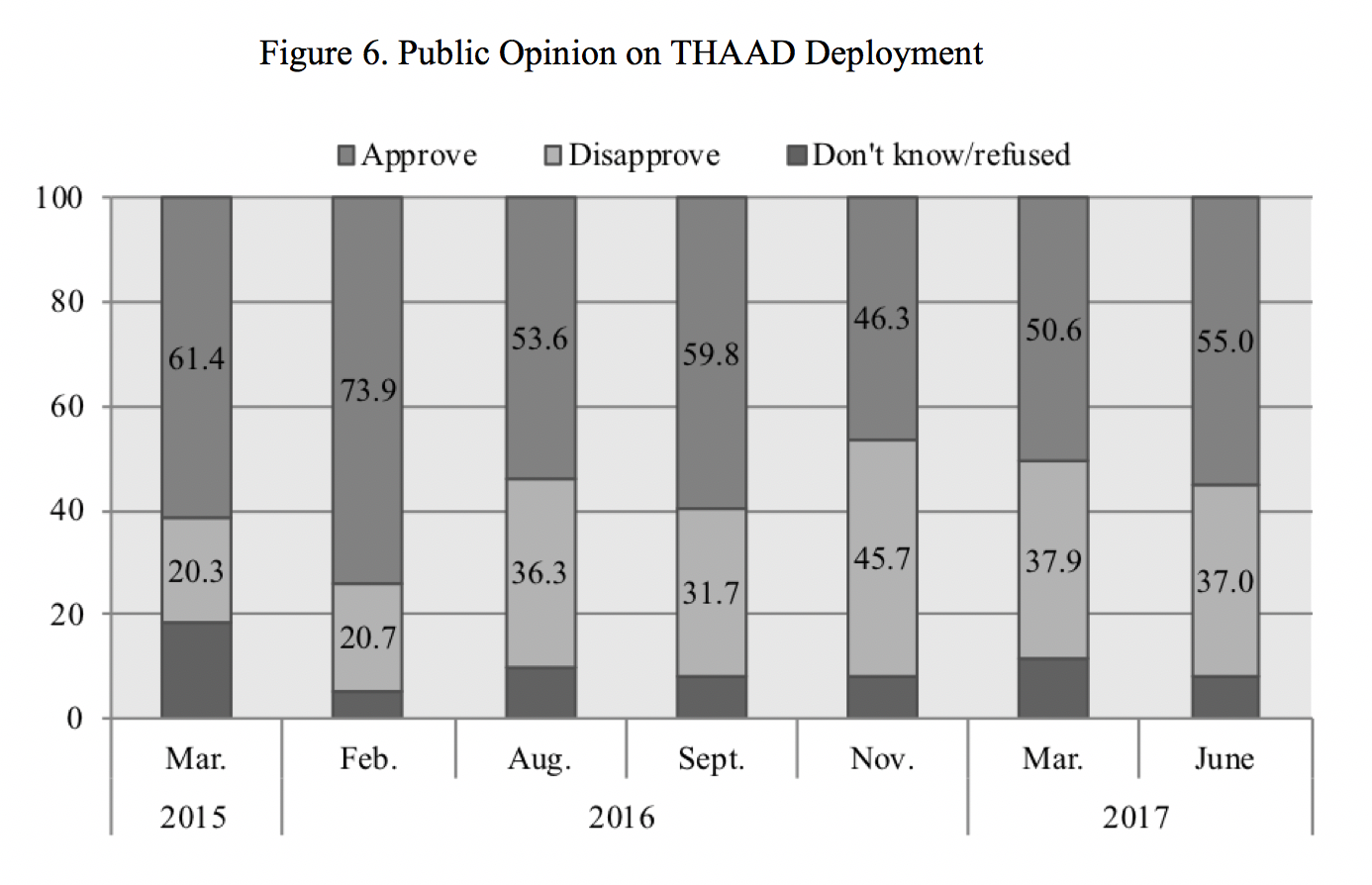

At the center of the changed attitude toward China by South Koreans is the controversy over the deployment of THAAD. South Koreans’ opinions about THAAD have been different at various times. Overall, they have supported almost all security measures since North Korea’s military provocations escalated. There was one point when South Koreans were evenly split between support and opposition in the course of 6 surveys regarding THAAD. It was in the survey conducted in November 2016. Around that time, Park was in huge political trouble and massive candlelight vigils were held every weekend nationwide. Her two most controversial foreign policies were THAAD deployment and the “comfort women” agreement with Japan, and both were under attack. Thus, the opinion over THAAD then reflected people’s negative sentiment and distrust toward Park and her administration. To many South Koreans, it was a deal that she and her security team had made behind the scene with the United States. After the impeachment and as North Korea’s military provocations increased and tensions on the peninsula escalated, people’s attitude toward THAAD turned somewhat more positive. The last time we asked their opinion was June 2017, and 55 percent of respondents approved the deployment while 37 percent opposed. As long as the North’s provocations and threats continue, South Koreans are likely to approve the deployment.

The whole debate surrounding THAAD deployment and soured relations between South Korea and China clearly affected how South Koreans view China. Furthermore, it also affected how South Koreans view the United States. Both countries are very important partners. China is the largest trading partner, which was the reason why many South Koreans were so worried about economic retaliation by China for THAAD. The United States is the most significant military ally of South Korea. As imminent threats from North Korea accumulate, reliance on the alliance becomes stronger. Provocative rhetoric from Trump did not matter much. Furthermore, as the relationship with China goes sour, the feeling that the United States is the only reliable partner deepens among the South Korean public.

Conclusion

While the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics has temporarily eased tensions, even raising further expectations for a breakthrough, military options for South Koreans for a cooperative partner have been narrowed down to one country. As North Korea escalates its nuclear and missile threats, the necessity for the alliance with the United States perceived by South Koreans has grown stronger. Although perplexed, South Koreans have been little affected by comments from how they view the United States. Attitudes toward the alliance have rather become more supportive. China’s economic retaliation provided an opportunity for South Koreans to reconsider the relations between two countries, deciding that it is not a reliable partner when it comes to security matters.

While doubt over how much the current South Korean government will cooperate with US North Korean policy may remain in Washington, support by South Koreans for the alliance with the United States is higher than ever. And, so far, the Moon government does not seem to be very far off from what the United States requests regarding North Korea policy. However, a fracture between the allies could arise from an unexpected point. What South Koreans are attentive to, besides the security alliance, is bilateral trade. Why and how China lost its magic charm so quickly is a good example. As Trump’s threat to KORUS FTA continues, we cannot exclude the possibility that this would hurt America’s public image among South Koreans. As seen in the Chinese case, being controlled and threatened by a superpower is the most disliked part by the South Korean people when it comes to relations with big countries. Of course, even under that situation, South Koreans will remain supportive of the alliance with the United States. Yet, it could be the starting point for the Moon government to gain substantial leverage with the South Korean public in taking the driver’s seat in new ways in foreign policy.

1. Seung-woo Kang, “U.S. Takes Sides with Japan on History Issue,” Korea Times, March 1, 2015, http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2015/03/116_174379.html

2. Yonhap, January 27, 2018, http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2018/01/26/0200000000AKR20180126134200002.HTML

3. Maeil Economy, January 31, 2018, http://vip.mk.co.kr/news/view/21/21/2902026.html

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn