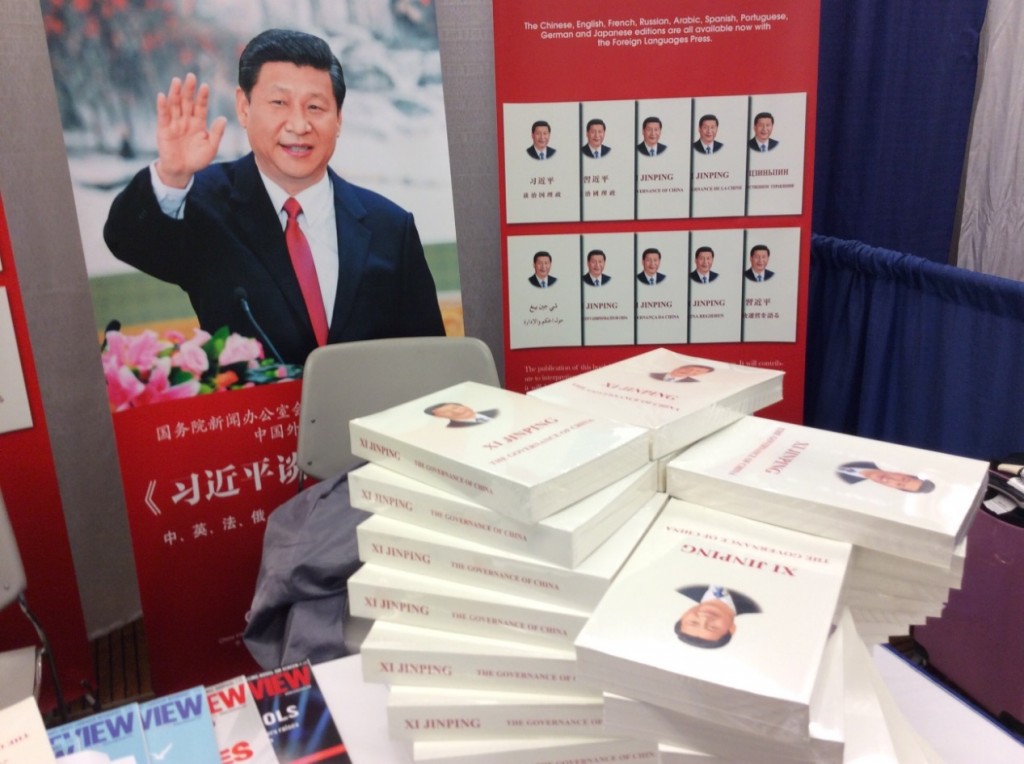

Xi Jinping’s latest book, The Governance of China, is popping up in odd places. It was prominently displayed on Facebook-founder Mark Zuckerberg’s desk when he entertained China’s Internet czar Lu Wei in December 2014. As Zuckerman explained: “I’ve bought copies of this book for my colleagues as well. I want them to understand socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Then in late March, Governance appeared at the annual Association for Asian Studies conference in Chicago—on the table of the China International Book Trading Corporation. Indeed, it was the only book on display—and it was free. (see Fig. 1)

Fig. 1: Xi’s Governance at the Association for Asian Studies, March 2015

Publication of Governance is a “political event,” directed not just at China’s domestic audience; through its English, French, Russian, Arabic, Spanish, Portuguese, German, and Japanese editions, it is promoted globally as a window onto Xi Jinping’s vision for China and the world. Since the English-language translation will be launched in the United States in late May, it is time to think about what this book means. First, I take the content of the book seriously to examine Xi’s hopes and plans for China, Asia, and the world. Second, I consider the role the book plays in China’s discursive politics to see if it is evidence of a new cult of personality. Lastly, I consider the impact of Governance.

Content: Xi Jinping’s Vision for China and the World

The book is helpful because it gathers together otherwise scattered speeches and comments to show Xi’s hopes, dreams, goals, and plans for China and the world.

The first chapter covers “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” a theme that continues throughout the book. The “China Dream” is described in the next chapter, the third chapter is about comprehensive reform, and so on. The book repeats various slogans that have animated Chinese politics since Deng Xiaoping asserted power in 1978: reform and opening, peace and development, core socialist values, harmonious society, etc. Again and again, it hammers home Xi’s objective of achieving the “Two Century” goals1 and the “China Dream” of national wealth and power. Contradictory values and goals are presented in Governance as a montage of happy images rather than in a logical causal chain, e.g.,(p. 188) Xi explains the importance of the core socialist values (prosperity, democracy, civility, harmony, freedom, equality, the rule of law, patriotism, dedication, integrity, and friendship), then (p. 190) lists 18 classical aphorisms—e.g. “A gentleman takes morality as his bedrock”—to show the enduring value of traditional Chinese civilization. If presented as a causal chain, then contradictions, e.g., between equality and hierarchy, would have to be resolved. But if they are presented as a montage—a list of “resources” from China’s ideological treasure box—, then Xi is able to manage the frictions between the hyper-modern values of socialism and the hyper-conservative values of Chinese tradition.

The Governance of China does not provide many clues about how such frictions will be managed. While leaders elsewhere might recognize different views among their citizens, Xi does not leave any room for debate. As do many scholars and officials in China, Xi presents China as a singular entity that effaces any discussion of alternative understandings. Readers either have to take Xi’s description of “China” as an indisputable fact—or leave it. If the content of Governance is largely familiar, then it is important to consider what is missing from this tome compiled “to enhance the rest of the world’s understanding of the Chinese government’s philosophy and its domestic and foreign policies” (publisher’s note, 1).

The chapter on “Multilateral Relations” gets a reasonable allocation of 41 pages, but rather than focusing on topics such as “Responsibility To Protect,” it treats multilateralism in terms of Beijing’s responsibility to lead Asia. The (in)famous “Asia for Asians” speech that Xi delivered in May 2014 underlines how the “China Dream” includes the “Asian Dream” of an American-free continent (p. 396). If we take the contents of this book seriously as a reflection of Xi’s global vision, then there is very little space in his world for the environment (only 4.5 pages of the 515-page volume), the United States, Japan, or Europe.

Style, Propaganda and Xi’s Personality Cult

In terms of presentation, this book screams ‘propaganda!’ Much like the Selected Works of Mao Zedong, its cover has a retouched portrait of the leader (here Xi Jinping) floating over the bright red book title, which is on a pale yellow background. In this edited collection of speeches, Xi comes off as a wise, tolerant, and generous leader. The heroic narrative is even stronger when you look beyond Xi’s speeches to the book’s visual and editorial framing: the most interesting thing about Governance are the 45 photographs of Xi and the “Man of the People” Appendix added by the publisher. Both stress how Xi values family and community: he is a respectful son to his father, a loving husband to his wife, and a caring father to his daughter (see Fig. 2). Xi’s life story is told, showing how he learned through suffering as a “sent-down youth” during the Cultural Revolution. (Since I have been examining the politics of public health in my documentary film, “Toilet Adventures,” I was fascinated to read that Xi spent his time in the Shaanxi countryside hauling manure.)

Fig. 2: Xi and wife, daughter, and father

From such experiences, the Appendix concludes that Xi has a great “affection for the common people” (p. 481). It goes out of its way to counter, albeit indirectly, Bloomberg news reports that Xi’s family has profited economically from his political position (pp. 494-495). The book shows how Xi commands respect at home and abroad: there are many pictures of foreign leaders such as Putin and Obama listening carefully to his advice. The Governance of China, thus, presents Xi as embodying the “China Dream” of the twenty-first century: the PRC and its leader are wise and strong, tolerant and hard-working, cultured and decisive. If this is the case, are we witnessing the emergence of a new cult of personality? Governance is part of a multimedia propaganda campaign facilitated by the CCP. Other items include the “Papa Xi Loves Mama Peng” music video that went viral in November 2014. Its folksy song presents the first couple as romantic role models for Chinese around the world. The Central Party School also created an app to read Papa Xi’s works and follow his activities online. Dubbed the “Little Red App,” its Chinese-language title—学习中国—blurs together Xi Jinping and China: it means both “study China” and “study Xi’s China.”

The public adoration is far from reaching the level of Mao’s Cultural Revolution personality cult. Yet, celebrations of Xi as an individual strongman indicate a marked shift away from the CCP’s commitment to collective leadership. Perhaps, this is what a twenty-first century-style cult of the personality cult looks like in China.

Hammers, Nails, and Impact

Although the intent may be to create a personality cult, just how influential is Xi’s The Governance of China? One way to measure the popularity of the book is by sales: the publisher claims Xi’s book has already sold four million copies, including 400,000 overseas. But as I saw in Chicago, the publisher had a hard time giving Governance away. In China, many of the “sales” are actually from bulk orders from party organizations for cadre study sessions. Still, the CCP does not expect a 100 percent return on its ideological investment. Propaganda work is not a one-off event, but succeeds through constant, multimedia repetition that creates the shared “new normal” of admiration for the General Secretary, as he is known in the PRC. The question is, how enduring will Papa Xi’s new normal be?

Xi’s advice on work-style to his fellow party cadres is telling:

[W]e need to have a ‘nail’ spirit. When we use a hammer to drive in a nail, a single knock often may not be enough; we must keep knocking until it is well in place. Then we can proceed to knock the next one, and continue driving in nails until the job is completely done. If we knock here and there without focusing on the nail, we may end up squandering our efforts altogether (p. 446).

Is The Governance of China a manifestation of the ‘nail spirit’ that hammers home Xi’s “China Dream” of the PRC as an authoritarian, civilization-state that has international influence backed up by a strong military? Or does Governance, and its cult-of-personality propaganda style, bring to mind the American idiom: “if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail?”

1. The “first century” will be the centennial of the founding of the CCP in 2021: the goal is for China to “complete the building of a moderately prosperous society” (小康社会), which includes doubling the 2010 per capita income by 2020. The “second century” is the centennial of the founding of the PRC in 2049; its vaguer goal by mid-century is to be ‘a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, civilized, and harmonious.”

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn