"The November Summits in Retrospect"

Summitry is often seen as a way for national leaders to directly hash out disagreements and reach some accommodation. That was not the case at this year’s East Asia Summit (EAS), where leaders seemed more interested in underlining their differences than reconciling them. Not surprisingly, the South China Sea dispute was the summit’s most contentious issue. The United States took a firmer posture on the issue than it had in the past. President Barack Obama urged the disputants “to halt [land] reclamation, construction, and militarization of disputed areas.” China, which has reclaimed over 2,900 acres of land in the Spratly archipelago, bristled at what it saw as American interference. Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Liu Zhenmin said that China would continue to build military and civilian facilities on the islands, and cautioned observers from conflating the construction of Chinese “military facilities with efforts to militarize the islands and reefs.”1

When China began its land reclamation, many in Southeast Asia downplayed the significance. But since then, China has expanded its construction efforts, building military-grade airstrips and port facilities. It has also sent more military forces into the area. In October alone, China deployed J-11 fighters, Type 022 fast attack craft, and an amphibious assault ship to the Paracel Islands. Adding to the region’s concerns, Liu stated that China had already demonstrated “great restraint” in the South China Sea by not seizing the rest of the disputed islands, even though it “has the right and ability to recover the islands and reefs illegally occupied by neighboring countries.” Soon after, Admiral Wu Shengli, the commander of the Chinese navy, used a similar expression to describe China’s reaction to supposed American provocations. Such developments have started to color how Southeast Asian countries view not only China, but also America’s posture in the South China Sea.2

For decades, the United States has maintained a hands-off policy towards the disputes in the South China Sea. It would not take sides as long as freedom of navigation through the area was ensured. It would only encourage the disputants to peacefully resolve their conflicts. But over the last half-decade, as China has ratcheted up its activities in the South China Sea, the United States has stepped up its military presence there. By and large, China has ignored such signs of American displeasure and instead accelerated its activities.

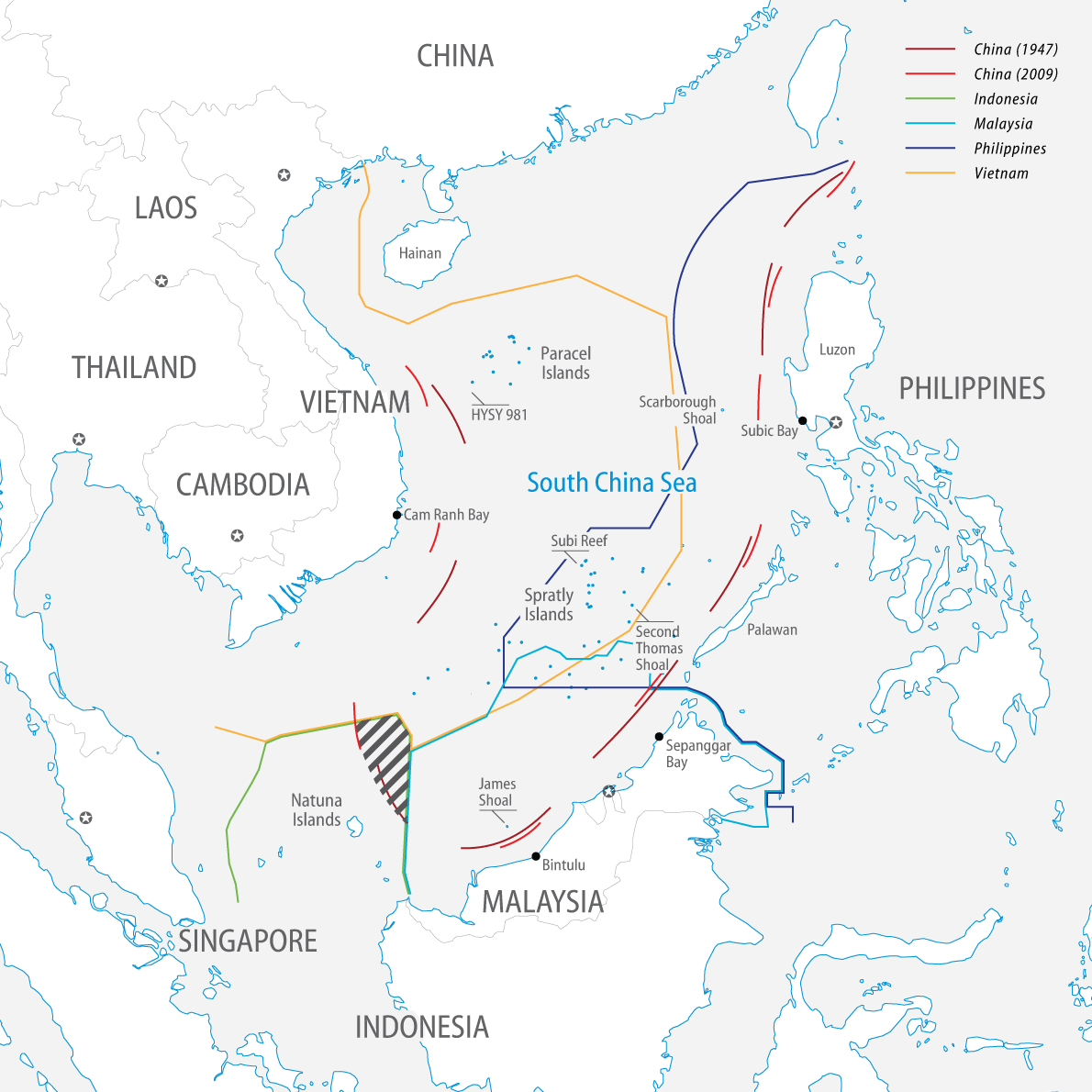

Ultimately, in December 2014 the United States directly interjected itself into the dispute. The Department of State published a technical report that documented the inconsistencies in China’s “nine-dash line” in the South China Sea, essentially questioning the basis for China’s maritime claims. Then, the United States began to openly challenge China’s claim to a 12-nautical mile territorial limit around its man-made islands, not recognized under international law. In October, the US Navy conducted a freedom-of-navigation operation through the South China Sea, sailing an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer through the 12-nautical mile radius around Subi Reef, one of the islets occupied by China and on which it reclaimed land and built an airstrip. A few weeks later, the US Air Force flew two B-52 bombers over the area, as it did in the East China Sea after China declared an air defense identification zone over its waters in 2013. Going forward, the US military announced that it would conduct at least two freedom-of-navigation operations through the South China Sea every quarter.3

A week after the EAS, the United States took yet another step. It passed new legislation to create the “South China Sea Initiative”—the first time that it specifically allocated funds to help Southeast Asian countries improve the security of the South China Sea. The initiative’s modest USD 50 million budget will be used for equipment, supplies, training, and small-scale military construction. It supplements other American aid already used to promote broader regional security. The increasingly firm posture taken by the United States has reflected Washington’s growing unease over the way China is changing the status quo in the South China Sea.4

A Reluctantly Changing Southeast Asian Worldview

How Southeast Asian countries have reacted to the firmer American posture has largely been a function of their evolving views of China and its intentions. For many years, most Southeast Asian countries had hoped that China’s priorities would come to mirror their own, where economic development takes precedence over political or territorial disputes and solutions are reached through multilateral dialogue and consensus. It is a formula that brought peace to the region—one that was ridden with conflict for much of the Cold War.

Thus, when China began its ascendance in the 1990s, Southeast Asian countries sought to acclimatize China into their norms. ASEAN put much stock in that strategy, which for a time seemed to work. China even signed ASEAN’s non-binding code of conduct on the South China Sea in 2002. Though little progress was made in settling the dispute since then, trade between China and Southeast Asia rapidly expanded. But over that same time Chinese economic and military power grew even faster, making Beijing feel freer to pursue its regional aims on its own terms.

Still, many Southeast Asian countries have been reluctant to abandon their hope that China would eventually come around to their worldview. Part of that reluctance is probably driven by their desire to keep external power competition out of Southeast Asia. During the Cold War, that sort of competition led to destructive wars across the region. Thus, Southeast Asian countries have been typically lukewarm to American overtures, which have tended to focus on security, rather than economic development.5

However, Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea has begun to change Southeast Asia’s perceptions of China and, in turn, its perceptions of the United States. With the construction of its new military outposts in the Spratly Islands, China is in a far better position to pursue what some have regarded as a strategy to establish de facto control over the South China Sea through the use of aggressive policing to gradually deny other claimants access to its waters. Naturally, those Southeast Asian countries that have been most exposed to China’s activities have embraced the greater American military presence the most. Those without any claims in the South China Sea dispute have been less keen on it. Those in the middle—countries that have claims in the South China Sea but have not yet felt the brunt of Chinese assertiveness—have equivocated.

Philippines and Vietnam

The Philippines was the first Southeast Asian country to feel serious Chinese pressure since the 1990s. Perhaps that was because it had become an easy target after it let its navy and air force wither away or because China wanted to test the resolve of its security treaty ally, the United States. Whatever the reason, Chinese provocations steadily increased. First, China detained Philippine fishing boats in the South China Sea. Then, in 2012 it blocked Philippine access to Scarborough Shoal, only 240 kilometers off the coast of Luzon. A year later, it prevented the Philippines from resupplying its outpost on Second Thomas Shoal. Having few other options, the Philippines countered China’s efforts by bringing a legal case against it at an international court.

Alone among Southeast Asian countries, the Philippines has openly called for more American engagement in the region. The United States responded, providing two coast guard cutters and transferring a third next year to help recapitalize the Philippine navy. Standing in Manila last month, Obama announced that the United States would provide USD 250 million to enhance Philippine maritime security. He also reaffirmed America’s “treaty obligation, an iron-clad commitment to the defense of our ally the Philippines.” Going one step further, President Benigno Aquino III has pushed for a new security arrangement, called the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), which would allow the US military to have a near-continuous presence in the Philippines. While implementation of the agreement has been delayed, it has underscored Manila’s interest in a stronger American military presence in the region.6

Vietnam has long been wary of both China and the United States. But Vietnam’s involvement in the South China Sea dispute has made China its bigger concern. Despite several attempts, Vietnam has never been able to reach any accommodation with China over their conflicting South China Sea claims beyond vague promises “to control disputes and safeguard peace and stability.”7 In the meantime, Vietnam also began to feel rising Chinese pressure. In 2011 and 2012, Chinese patrol boats cut the seismic survey cables used by Vietnamese oil exploration ships. A much bigger row erupted in 2014, when China set up an offshore oil drilling rig, the Hai Yang Shi You 981, in Vietnamese-claimed waters. Recently, Vietnamese supply ships sailing to the Spratly Islands have found their paths blocked by Chinese vessels. In November, a Chinese warship from Subi Reef even unsheathed and trained its deck gun on a supply ship to frighten it away. No wonder Vietnam has begun to arm its fisheries patrol craft.8

Though Vietnam has not been a vocal supporter of America’s firmer posture in the South China Sea, it has repeatedly invited US warships to its Cam Ranh Bay naval base. Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung even said that he “would welcome the United States playing a larger role in tempering regional tensions.”9 This year, Vietnam hosted Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter, who pledged USD 18 million to expand the country’s coast guard. Even so, Vietnam is not counting on the United States alone. It has concluded military cooperation agreements with Brazil, India, Japan, and Russia. Closer to home, it took the extraordinary step of military cooperation with another South China Sea disputant, the Philippines. Both need time to beef up their defenses. As long as US efforts in the region buy it more time to do so, Vietnam is likely to approve, if quietly.

Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand

By contrast, Cambodia and Laos have apprehensively watched America’s growing military activities. In particular, Cambodia has argued that external powers should stay out of the disputes in the South China Sea. It would rather see the disputes managed through bilateral negotiations between the disputants, as China advocates. Indeed, China can usually count on the support of Cambodia, whose economy is heavily reliant on Chinese foreign direct investment and trade. In recent years, China has also courted Laos, a traditional ally of Vietnam, with economic aid from its “One Belt, One Road” initiative. Construction on a Chinese-financed railway connecting China and Laos began in December.10

That railway is now expected to extend to Thailand, the only major Southeast Asian country with no direct stake in the South China Sea dispute. While it is a longtime ally of the United States, relations between the two countries have been strained since Thailand’s military coup in 2014. Thai military leaders, stung by American sanctions after the coup, have warmed to China. They recently approved not only the railway’s development, but also closer military ties with China. Beijing reciprocated by buying one million tons of surplus rice from the Thai government, freeing it of a massive financial burden.11 So far, Bangkok has kept mum on America’s firmer posture in the region.

Malaysia and Indonesia

Another country that has kept a low profile on the South China Sea dispute is Malaysia. Despite its own claims in the disputed waters, it has consistently played down Chinese provocations, long believing in the importance of continuing its dialogue with China. Hence, Malaysia has led ASEAN’s attempts to acclimatize China into its multilateral norms. That was still Malaysia’s approach last year when it feted the fortieth anniversary of its diplomatic relations with China.

But one can see strains in their relationship. In 2013 and 2014, China staged amphibious exercises off Malaysian-claimed James Shoal. Malaysia issued a rare protest to China. The exercises prompted it to establish a marine corps and build a naval base at Bintulu, near the disputed shoal. No doubt, the pace of Chinese land reclamation and military outpost construction in the South China Sea has disconcerted Malaysian leaders. In November, Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi uncharacteristically complained about China’s island building in a public speech. Attentive to Malaysia’s drift, China has tried to halt it by helping Prime Minister Najib Razak recover from a domestic scandal over a debt-ridden investment fund that he founded. China purchased USD 2.3 billion in assets from the fund to help keep it afloat.12 Even so, Najib has stated that he understands why the United States has taken the posture that it has and that it is a “position consistent with its role.”13

Indonesia has taken a different approach to stay above the fray. Whenever asked about Chinese claims in the South China Sea, its diplomats artfully answer that Jakarta has no territorial dispute with China, which is true, but what they fail to mention is that it does have a maritime dispute with China. Waters claimed by Indonesia as part of its exclusive economic zone overlap with those enclosed by China’s “nine-dash line” (see hatched area on map).14 After a 2013 incident in which Chinese warships forced Indonesian authorities to release a Chinese fishing boat captured in those waters, Indonesia’s military has made defending the area around the Natuna Islands a high priority. President Joko Widodo likely approves. He has taken a harder stand toward illegal fishing in Indonesia’s waters. In May, Indonesia blew up several captured fishing boats, including a Chinese one. In November, Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs Luhut Panjaitan said Jakarta could take China to an international court if dialogue over the South China Sea fails.15

Nevertheless, Indonesia’s relations with the United States have been slow to warm after years of US sanctions against Jakarta. Only recently has Indonesia become more receptive. In 2012, it accepted an offer of 24 F-16 fighters with upgraded with maritime and strike capabilities from the United States. This year, Joko announced that Indonesia would join the US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership FTA. While Indonesia has not openly supported America’s firmer posture, until it can strengthen its forces on the Natuna Islands a stronger American military presence should give it some comfort.

Conclusion

China and the United States are increasingly at odds over the South China Sea dispute. Both have taken firmer stands on the issue. Just how firm was made clear by the difficulty the conferees at this year’s EAS had in agreeing to a customary joint statement. The statement eventually took three days, longer than the summit itself, to finish. The United States and the Philippines likely supported an early version of the statement, which included language that noted China’s land reclamation efforts. No doubt, China and Cambodia opposed it. By the final draft, that language was dropped and replaced by an oblique reference to “serious concerns expressed by some leaders over recent and on-going developments in the area.”16 Still, one could consider that as progress. A week earlier at the annual ASEAN defense ministers’ meeting, no agreement was ever reached on its joint statement.17

China is changing the status quo in the South China Sea. How seriously those changes have impacted individual Southeast Asian countries has driven the degree to which each has welcomed the firmer posture of the United States. Certainly, they all have benefited from China’s tremendous economic growth and are understandably hesitant to spoil that, especially those countries with no claims in the South China Sea. Some still cling to the hope that China will come around to embrace ASEAN’s multilateral norms. They remain reluctant to concede that China may never come to adopt their worldview. But China’s recent actions in the South China Sea are causing many of them to lose hope.

Some see an emerging Chinese strategy to incrementally establish de facto control over the South China Sea. It has already prevented Philippine authorities from operating near many of their disputed islands and resupplying those that they occupy. China has begun to do the same to Vietnamese-held islands. Indonesia and Malaysia are beginning to wonder whether their maritime claims are next. China is doing its best to blunt criticism of it with economic largesse from its “One Belt, One Road” initiative. How Southeast Asian countries perceive China and its intentions will govern their reactions to America’s firmer posture in the region. China risks becoming its own worst enemy. The harder China pushes, the more the United States gains.

1.David Tweed, “China Says South China Sea Construction Is Protecting Distant Reefs,” Bloomberg, November 22, 2015; Megha Rajagopalan and Praveen Menon, “China Says Won’t Cease Building on South China Sea Isles,” Reuters, November 22, 2015; Matt Spetalnick and Rosemarie Francisco, “Obama Puts South China Sea Dispute on Agenda as Summitry Begins,” Reuters, November 17, 2015.

2.Richard D. Fisher, “Posturing continues in the South and East China Seas,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, November 26, 2015; John Ruwitch, “China’s Navy ‘Restrained’ Facing US Provocations: Admiral,” Reuters, November 20, 2015; Michael Martina, “China Says Has Shown ‘Great Restraint’ in South China Sea,” Reuters, November 17, 2015.

3.Andrea Shalal and David Brunnstrom, “US Likely to Make Another South China Sea Patrol before Year-end: Navy Official,” Reuters, November 20, 2015.

4.Jon Grevatt, “United States Enacts ‘South China Sea Initiative,’” Jane’s Defense Weekly, November 26, 2015.

5.That is why the US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership FTA has been a useful addition to America’s engagement approach with Southeast Asia.

6.Spetalnick and Francisco, “Obama Puts South China Sea Dispute on Agenda as Summitry Begins.”

7.“China, Vietnam Pledge Closer Friendship, Partnership,” Xinhua, April 7, 2015; “China and Viet Nam Hold the Seventh Meeting of the Steering Committee for Bilateral Cooperation,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China press release, October 27, 2014.

8.“Chinese Warship Soldiers Point Guns at Vietnamese Supply Boat in Vietnam’s Waters,” Tuoi Tre News, November 27, 2015; “Vietnam Accuses China of Beating Fishermen, Demands Punishment and Compensation,” Associated Press, September 10, 2014.

9.Chun Han Wong, “Vietnamese Prime Minister Welcomes Larger Role for US,” The Wall Street Journal, June 1, 2013, http://blogs.wsj.com/indonesiarealtime/2013/06/01/vietnamese-prime-minister-welcomes-larger-role-for-u-s.

10.Tamaki Kyozuka and Tetsuya Abe, “China Starts Work on Laos Railway, Eyeing Farther Horizons,” Nikkei Asian Review, December 3, 2015; Somsack Pongkhao, “Laos Supports China’s One Belt, One Road initiative,” Vientiane Times, September 22, 2015.

11.“UPDATE 1-Thailand Draws Nearer to China with Rail, Rice and Rubber Deals,” Reuters, December 3, 2015.

12.P.R. Venkat and Rick Carew, “China’s Clout in Malaysia Set to Grow After 1MDB Deal,” The Wall Street Journal, November 25, 2015; “Malaysian Deputy PM Says Must Defend Sovereignty in South China Sea Dispute,” Reuters, November 14, 2015.

13.Remarks by Preside Barack Obama and Prime Minister Najib Razak, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, November 20, 2015.

14.Whenever asked about Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone, Chinese diplomats equally artfully answer that China does not claim the Natuna Islands, leaving aside their maritime dispute in the South China Sea.

15.Randy Fabi and Ben Blanchard, “Indonesia Asks China to Clarify South China Sea Claims,” Reuters, November 12, 2015; Randy Fabi, “Indonesia Says Could Also Take China to Court over South China Sea,” Reuters, November 11, 2015.

16.Chairman’s Statement of the 10th East Asia Summit, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, November 25, 2015; Hideki Yabu, “Muted Tone on Maritime Issue,” NHK World, November 24, 2015, http://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/english/news/insideasia/20151125.html.

17.Yeganeh Torbati and Trinna Leong, “ASEAN Defense Chiefs Fail to Agree on South China Sea Statement,” Reuters, November 4, 2015; “No Joint Declaration at Asia Defense Meeting amid Sea Tensions,” Associated Press, November 4, 2015.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn