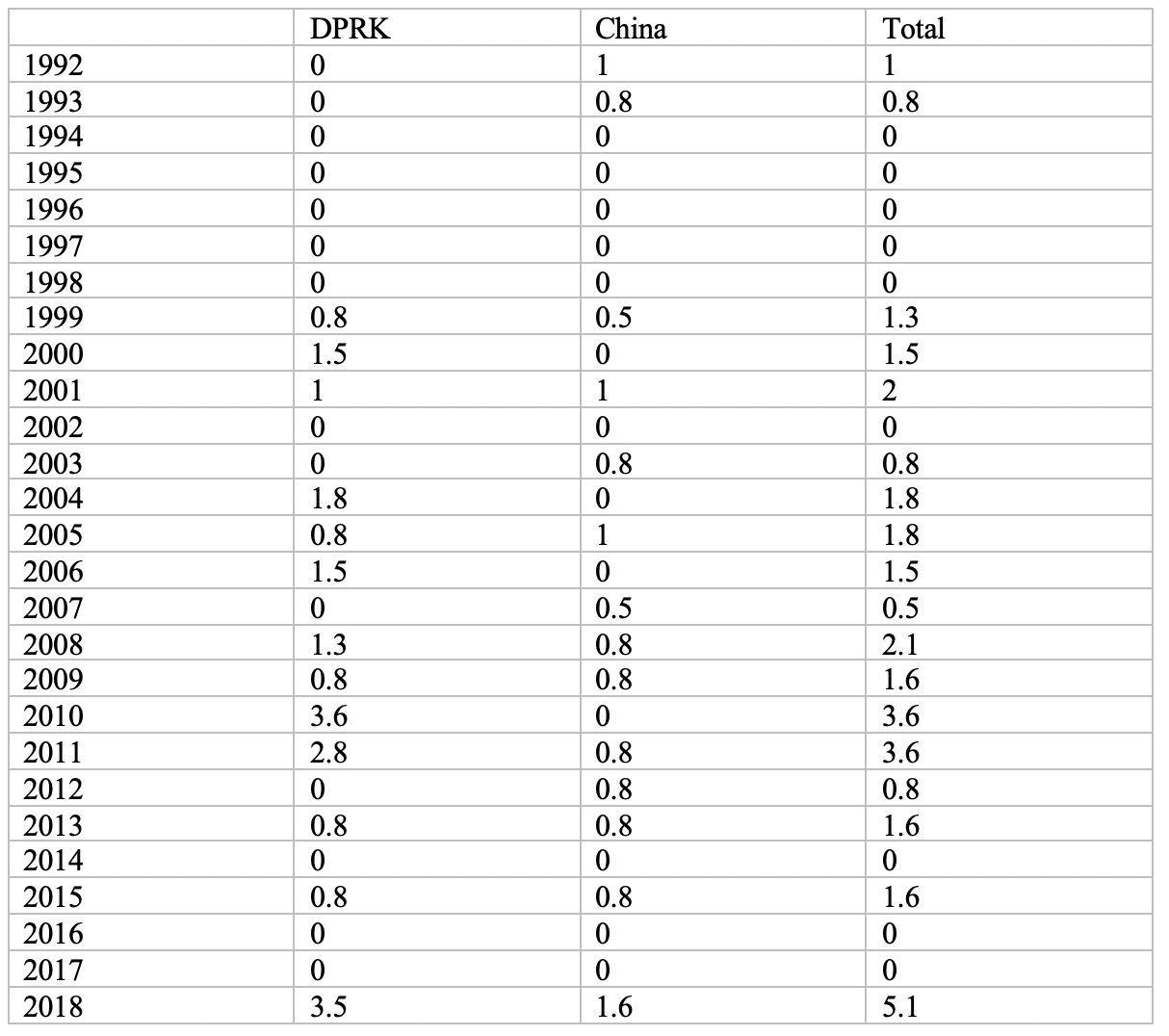

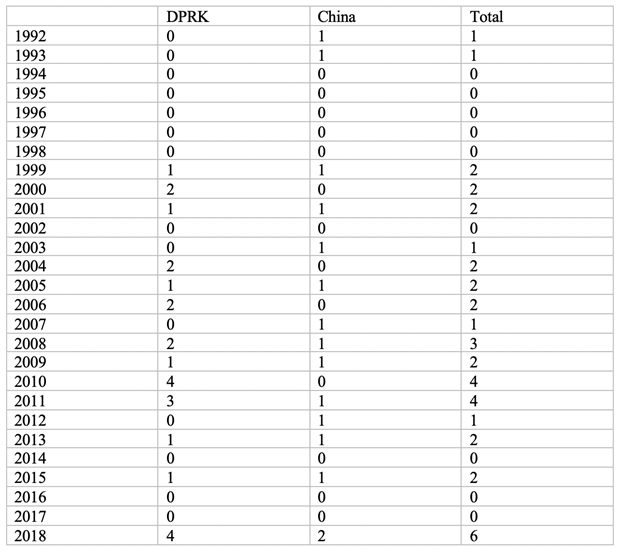

Exchanges of visits between Chinese and DPRK leaders and high-level delegations have been relatively rare since the end of the Cold War. However, meetings between leaders saw three abnormal peaks in 1999-2001, 2010-2012, and 2018-2019. If after the Cold War the bilateral relationship cooled, room was left for China’s leaders to respond to changes in the Sino-US relationship, which repeatedly proved to be the major external factor affecting China-DPRK ties. When conflicts arose between China and the United States, the relationship between China and the DPRK would grow closer; when China and the United States were friendly to each other, China-DPRK relations would be alienated. Not only have there been three spikes in interactions, the degree of closeness has grown from one spike to another. Given factors identified below, there is reason to surmise that the recent peak in leadership communications represents a point of no return, making it unlikely that another deep trough in ties lies ahead, although the year 2020 has seen both Beijing and Pyongyang close their borders in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chinese thinking about North Korea

The Korean Peninsula, at the center of Northeast Asia, has long been a bone of contention for neighboring states, and from the late nineteenth century it became a hot spot in geopolitical rivalries. After the split between North and South, North Korea (DPRK) was considered a “strategic buffer zone” for China’s national security and a two-way shield between mainland and maritime countries. Shortly after the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), it and North Korea formed a “brotherhood,” a key factor in China’s decision to fight against the US in Korea. Over time, the existence of this brotherhood served as a common perception in China and the entire world. However, the ups and downs of China-DPRK relations defied this simplistic perception. There was volatility in the Cold War era and, later, as North Korea became a de facto nuclear weapons-possessing state, China-DPRK relations were subject to higher volatility. After China participated in United Nations sanctions against the DPRK in March 2013, relations turned cold again. Heads-of-state visits halted, and the official media of both countries published very few reports on bilateral relations. After China announced its embargo against North Korea in 2017, both sides even openly blamed each other. In 2018, the situation suddenly improved. Just one month before his summit with Donald Trump, Kim Jong-un visited China twice and proposed a "new strategic line," which brought China-DPRK relations back onto a positive track.

China has multiple motives for its policies toward North Korea. Some have mentioned the shared socialist legacy and sacrifices of the Korean War. Others speak of geographical needs such as boosting economic prospects for Northeast China and avoiding refugee inflows. The record of the past three decades supports another explanation as primary: the geopolitical factor centered on the United States. Changes in China-US ties explain the three spikes in China-DPRK relations after the Cold War, I argue below. South Korea’s behavior, thus, is not a big factor in China’s policy choices toward North Korea, which are viewed primarily through the prism of the Sino-DPRK-US triangle. Even North Korea’s actions have only been a secondary factor to the US. They have angered China at times, but North Korean policies toward China have mattered less than US ones. The main driving force in China’s thinking about the DPRK is Chinese thinking about Sino-US ties.

The so-called brotherhood between China and the DPRK is a misunderstanding. The DPRK mainly followed the Soviet Union during the Cold War. After the Cold War, it hardly assumed any security, political, or economic dependence on China, either. China was not an intimate friend, let alone a "big brother." Bilateral ties, if friendly, were based merely on the shared ideology. North Korea needed China to balance against the United States in the strategic dimension, but for its leaders their own political security and independence were the primary concerns. China fully recognized that in the eyes of North Korea, the United States is the key threat to its national security. Strengthening ties with China served solely to enhance North Korea’s independence and international influence. In this sense, China’s influence on North Korea has remained limited.

In the 1960s, the resumption of China-DPRK ties reflected maneuvering between major powers, not bilateral brotherhood. The divide between China and the Soviet Union gradually deepened, and in 1965, Brezhnev increased his economic and military assistance to the DPRK. However, under the influence of extreme leftism, China could not tolerate the DPRK’s ambiguous attitude. In the late 1960s, the situation on the peninsula was tense, and the US was tough on the DPRK. North Korea was in desperate need of China’s support. It coincided with the Zhenbao Island skirmish which froze China-Soviet relations. Thus, in 1969, Choi Yong-gun’s visit to China restored friendly relations to ensure its security interests, temporarily ignoring differences.

After the Cold War, major differences regarding their core interests reemerged between China and the DPRK. China gave priority to economic development and no longer crafted its diplomatic policies on the basis of ideology alone. It sought to fit into the international community, following the US-led world economic order, and establishing friendly ties with neighboring developed countries such as Japan and South Korea to get their capital, technology, and markets. However, North Korea’s internal and diplomatic principles were still based on Cold War principles. The disintegration of the Soviet Union, the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and South Korea, and the long-term hostility with the US made it vulnerable to serious external threats. It began its nuclear program to guarantee its own security, which harmed China’s core interests in at least three respects: 1) the nuclear issue raised tensions on the peninsula, undermining China’s security environment and the conditions it had created for economic development; 2) nuclear tests pose increased safety risks, including nuclear leaks, unauthorized launches, and nuclear terrorism; and 3) this challenged the NPT order, while China’s accession to the NPT in the 1990s represented its desire to fit into the international community at the political and security levels.

China’s policy toward the DPRK combined geopolitical calculus, economic interests, historical and realist factors, and most of all an attempt to maintain peace and stability on the peninsula. However, the structural security problems troubling North Korea could not be resolved, and China was not willing to provide security guarantees as the DPRK demanded. From 2003 to 2009, its diplomats repeatedly denied the existence of a “China-DPRK alliance.” In light of pressure from the US and its allies on the DPRK, China gradually shifted its focus from maintaining stability to putting more pressure on the DPRK. In 2013, it participated in the UN sanctions against the DPRK, which further dampened China-DPRK ties, given the determination of China to act as a responsible world power and North Korea’s strong commitment to its nuclear program.

Traditional friendship and geopolitical conditions led to the revival of normal economic and trade exchanges between China and the DPRK. Ties were “cold but not dead.” However, some Chinese experts came to regard North Korea as a strain on China’s foreign policy, arguing that China and the United States should coordinate their positions to get North Korea to abandon its nuclear program as soon as possible. In 2016, Foreign Minister Wang Yi reaffirmed that China and the DPRK had a "normal country-to-country relationship based on a profound tradition of friendship," but he reiterated China’s commitment to denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula.

The influence of China-US relations on China-DPRK relations after the Cold War

Focusing on Chinese thinking about North Korea cannot explain the three abnormal spikes in bilateral ties in the past 20 years. Comparing China-DPRK relations with China-US relations, however, shows that slumps in China-US ties coincided with the three peaks in China-DPRK relations. Whereas some observers have stressed the flow of US-DPRK relations, showcasing each shift in US willingness to talk or offer some assurances or each move by North Korea to join in talks or hint at its conditions for a breakthrough, I argue that neither China nor the DPRK has expected much from this relationship. Thus, DPRK-US relations generally appear as a constant in China and North Korea’s policy orientations. North Korea could rely on China to counteract the United States. Change in China-US relations is what primarily affected the distance between China and the DPRK as seen in each of the three spikes in China’s relationship with the DPRK.

China-US relations in 1999-2001 and the first spike in China-DPRK relations

The political turmoil of 1989 shocked China-US relations, completely exposing the differences in political system and ideology, which have underlined the cyclical setbacks in bilateral relations. After Bill Clinton became president, conflicts between the two in ideology and human rights soared. In 1995, the US issued a visa to Lee Teng-hui, which triggered a political crisis. In order to counteract US policy and warn Taiwan’s independence forces represented by Lee, China conducted military exercises which were, however, soon followed by the Clinton administration’s tough stance in sending warships to the Taiwan Strait. The administration even put China on the list of targets for a nuclear strike. Relations returned to the starting point, forcing both sides to reexamine their bilateral future. During its second term, the Clinton administration shifted to a “congagement” strategy towards China, while the tensions between them remained.

The bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999 again sent relations into a trough. Demonstrations broke out across China, strongly condemning US hegemony. But the US claimed that it was just a "tragic mistake." Vice President Hu Jintao promptly delivered a televised speech condemning the brutal atrocities of NATO. Dialogue and cooperation in the field of security halted completely. On April 1, 2001, a US EP-3 reconnaissance plane collided with and damaged a Chinese fighter jet that was monitoring the US spying operations over the South China Sea, resulting in China’s protests to the US. This series of incidents drove relations from bad to worse. President George W. Bush made it clear during his election campaign that China is a rival rather than a strategic partner. His administration’s Asia-Pacific strategy saw China as the primary potential adversary and the key target of the US military. The United States opted to "support Japan to suppress China," regarding Japan as the cornerstone of its regional strategy and China as a strategic rival, and it enhanced ties with Taiwan and showed a tough stance towards China.

In short, from 1999-2001, the tensions between China and the United States were obvious. While China-DPRK relations had plummeted after the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and South Korea, in June 1999, Kim Young-sam visited China, resuming high-level visits. Soon foreign ministers exchanged visits. In September 2001, President Jiang Zemin paid a visit to the DPRK. China and the DPRK began to acknowledge each other’s political position, which improved the relationship. In Jiang’s visit, China’s statement mentioned that both sides had reached a consensus on the further development of relations in the new century and on major international and regional issues of common concern, in addition to reaffirming the traditional friendship. Soon, People’s Daily published an editorial, emphasizing that “the world is diversified, and all countries should explore their own development path based on their actual conditions… China and North Korea are firmly advancing along the socialist road with their own characteristics." Both the statement and the editorial acknowledged the similarities between China and the DPRK in terms of political system and ideology, their shared position on major international and regional issues, and their opposition to US hegemony. The deterioration of China-US relations can thus be seen as an important reason for closing the China-DPRK gap.

The 9/11 attack gave China and the United States an opportunity to repair their relations. Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan said, "In the fight against terrorism, the Chinese people stand together with the American people and the entire international community." The next day, in a phone call Jiang Zemin and George W. Bush agreed to cooperate on counter-terrorism issues. In addition to the war in Afghanistan, the DPRK nuclear issue was a major concern of the United States. Secretary of State Colin Powell once said to President Hu Jintao, "Please continue to play an important role as you are already doing, as our forerunner, as the convener and participant of the Six-Party Talks." Both China and the United States were aware of each other’s importance in the DPRK nuclear issue, so denuclearizing the peninsula became a common interest. Thanks to the efforts of China and other parties, the Six-Party Talks began in 2003. China gradually became a “stakeholder” of the United States in the political and security fields. Before the stagnation of the Six-Party Talks since 2009, China-US relations showed steady momentum during the Bush presidency.

China was clearly aware that it would be impossible to truly achieve denuclearization unless the structural security dilemma facing North Korea could be “properly” addressed. At no point during the Six-Party Talks did China think that the US was ready to do so, in accord with the logic of Chinese geopolitical reasoning. Thus, the seeds of collapse in US-DPRK relations were present. China had championed the Six-Party Talks partly to strengthen cooperation with the United States in the field of non-proliferation and counter-terrorism, also hoping that this would help maintain peace and stability in this region. Warming relations with the United States inevitably affected China-DPRK relations, but this was a price China was prepared to pay until US ties deteriorated.

China-US relations in 2010-2012 and the second spike in China-DPRK relations

Around 2010, profound changes occurred in China-US relations as both vied for new development opportunities and strategic advantages. Under a calm surface, bilateral relations were subject to severe challenges. The global financial crisis from 2008 rocked the Western developed countries including the United States, opening a Pandora’s Box. Although China expressed its willingness to cooperate in global economic governance, the power balance began to tip towards China. In 2010, after China overtook Japan to become the world’s second largest economy, tensions began to rise with the US. Competition outweighed cooperation.

The Obama administration took on China. In 2010, the Department of Commerce announced its intention to carry out anti-dumping and anti-subsidy investigations of China’s export of steel products to the US, and finally ruled that anti-dumping duties should be imposed on Chinese steel pipes. China expressed strong objection to US protectionism and retaliated by imposing tariffs on American exports. Since then, the two have engaged in a tariff game that involves various industries such as agricultural products. The Senate subsequently passed the "Currency Exchange Rate Oversight Reform Act of 2011" intent on punishing China for "currency manipulation," which seriously affected normal economic relations–the forerunner of the current trade war.

In addition, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced in Foreign Policy that the United States would return to the Asia-Pacific, clearly elaborating US strategy after the “pivot to Asia” was announced in 2009. In 2012, the Department of Defense officially renamed the strategy “Asia-Pacific rebalancing.” In economics, the Obama administration tried to get the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) endorsed, which is widely interpreted in China as an attempt to establish a US-led regional economic alliance based on a high-level free trade agreement, thereby excluding China from this region. In politics and security, the US further strengthened bilateral ties with allies in the Asia-Pacific region such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the Philippines, and pivoted its military forces to the Asia-Pacific region. It declared that the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan applied to the Diaoyu Islands and supported Japan’s military expansion and constitutional revision, along with US intervention in the South China Sea disputes. All this put huge pressure on China’s regional security. Therefore, China regarded the US strategy of “Asia-Pacific rebalancing” as a policy of containment against China aimed at consolidating US hegemony. During this period, American politicians talked loudly about "threats from China" and "China’s responsibility," which again hurt China-US relations.

High-level exchanges between China and the DPRK were frequent during this period. From 2010 to 2011, seven high-level DPRK delegations came to China, and Chinese leaders visited North Korea once. North Korea’s resumption of nuclear tests in 2009 and withdrawal from the Six-Party Talks had had a tremendous negative impact on China’s regional security and soft power. However, contacts became unexpectedly close. To a great extent, the alienation between China and the US during this period spurred the exchanges between China and the DPRK. Kim Jong-il paid visits to China, reiterating the importance of cooperation between China and the DPRK in economy and trade. In addition, China and the DPRK emphasized their common interests in maintaining regional stability. In 2011, Vice Premier Li Keqiang visited North Korea, saying that both sides should "cherish our traditional friendship and handle the bilateral relations from a strategic and long-term perspective," implying that cooperation should not be confined to the economic and trade fields and the focus should not rest solely on the tactical aspect. Instead, both countries should try to address the common challenges facing socialist countries from a strategic perspective in a complex international environment. China and the DPRK had some differences at the tactical level on issues such as nuclear safety and non-proliferation, but considering the shared political system and ideology, and the need to balance the US hegemony, the two countries still looked at each other as trustworthy strategic partners.

As had happened from 2001, as China-US relations had recovered, China-DPRK relations grew cold again. After Obama was re-elected in 2012, then Vice President Xi Jinping visited the United States, arguing in a speech that China-US friendship met the needs of the times. He proposed to build a new model of major-power relations between the two. In June 2013, as president he met Obama at the Annenberg Retreat, both pledging to build this new model with no conflict, no confrontation, but mutual respect and win-win cooperation. Meanwhile, the US trade deficit with China shrunk, the currency exchange rate issue began to cool down, and the trade war was not expanding. China and the US carried out effective cooperation on a number of global governance issues, e.g., addressing climate change and fighting the Ebola virus. China not only supported the Nuclear Security Summit mechanism championed by Obama, but also began to join the UN sanctions on the DPRK, publicly exerting pressure to denuclearize. China worked hard to make the Iran nuclear deal possible. Nuclear non-proliferation again became a highlight in cooperation.

China-US relations in 2018-2019 and the third spike in China-DPRK relations

In 2017, Trump’s administration exerted "extreme pressure" on North Korea, and the Korean Peninsula was on the verge of war. During the initial period of his presidency, China mistakenly believed that the new model of major-power relations would remain effective. This can be seen in statements concerning Trump’s visit to China in late 2017. Similarly, in dealing with the worsening nuclear issue, China exerted pressure on North Korea, embargoing commodities such as coal and steel, which triggered a very rare public verbal war between China and the DPRK. China-DPRK relations fell to the lowest level in history.

However, from late 2017 to early 2018, China-US relations and the DPRK-US relations experienced U-turns at the same time. After the Trump administration published its new National Security Strategy, which defined China as a "major strategic rival," tensions soared in trade, security, and ideology. Soon, the Trump administration launched a hostile campaign against China, exerting extreme pressure, containment, and even decoupling. The trade war escalated, with both sides imposing retaliatory tariffs on the other, setting up investment and trade barriers, and even extending the fire into the high-tech field on the grounds of cyber security. The Huawei incident was a case in point. The China-US trade war came to cover all aspects of trade, investment, technology, and security. Chinese academia generally believed that the Trump administration had shown unprecedented determination to contain China since the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and the United States. The sharp fall in relations was not only due to accumulated grievances on both sides around the political system, ideology, and economic and trade issues, but also the so-called "Thucydides Trap." Meanwhile, Trump also hardened US positions on the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, defying China’s core interests.

While China-US relations turned sour, DPRK-US relations suddenly improved. In an unexpected way, Trump broke the deadlock between the DPRK and the United States, or the rigid cycle of nuclear tests and sanctions/military exercises, and built certain grounds for mutual trust and renewed denuclearization negotiations. Of course, the conflicts between the DPRK and the United States cannot be solved through occasional summit meetings. Differences persist: to abandon nuclear weapons first or to lift sanctions first? to reach a package agreement or to take a step-by-step approach to solve the nuclear issue.

China-DPRK relations heated up rapidly while DPRK-US tensions eased; however, North Korea at this point was already a de facto nuclear weapons-possessing country, more optimistic on pursuing an independent foreign policy. In March 2018, Kim Jong-un visited China. During his talks with Xi Jinping, he said that the DPRK was firmly and always committed to denuclearizing the peninsula. However, he also said that "as long as the DPRK is not subject to nuclear threats, the DPRK will never use nuclear weapons or disclose nuclear weapons and nuclear technology." The implication is that the DPRK was already a responsible nuclear weapons-possessing state, like others. Kim’s visit to China was meant apparently to coordinate positions while relations with the United States were improving, but Kim had not come to listen to China’s instructions. This can be seen in Kim’s statements on the nuclear issue. During Kim’s visit in May, Xi expressed his appreciation of the DPRK’s announcement to suspend nuclear tests and abandon the nuclear test site in the north. When Kim visited China again in June, Xi said, "The firm commitment of China to developing China-DPRK relations will not change. The Chinese people’s friendship with the Korean people will not change. China’s support for the socialist DPRK will not change." This reflected a shift back from cooperating with the US against the DPRK to supporting North Korea. China did not want the situation on the peninsula to deteriorate, but it is even less eager for the DPRK to help the US exert greater geopolitical pressure on China after the easing of DPRK-US relations. China’s participation in the process to address the DPRK nuclear issue was not only relevant to safeguarding China’s core interests, but also potentially helpful for China and the US to find common ground on the peninsula. This failed as bilateral relation also were left adrift.

In January 2019, Kim visited China for the fourth time, which was interpreted as a New Year goodwill visit. In June, Xi Jinping paid a state visit to the DPRK, after a suspension of 11 years. Such frequent meetings not only gave Kim Jong-un more confidence in dealing with Trump, but also helped to generate real economic and technical support from China, seen as enabling North Korea to realize its strategic goals after becoming a nuclear weapons-possessing country. China had not meant to help Trump on the DPRK nuclear issue, but wanted to balance against the United States. In the context of the escalating trade war with the United States, the two meetings in 2019 were especially meaningful. Kim Jong-un’s visit in January coincided with conflict escalation in which China and the US imposed tariffs on each other. In June, the trade war underwent a period of tit-for-tat, and it was hoped that the leaders of China and the United States would restart negotiations at the G20 summit. On the eve of that summit, China suddenly announced that Xi Jinping planned to visit North Korea. There, Xi not only emphasized the need to maintain strategic communications between China and the DPRK, but also stated for the first time that "China is willing to provide assistance to the DPRK to address its own legitimate security and development concerns." Although the exact implications of this statement are not clear, it is likely that China has made a positive commitment to the issue of security, about which the DPRK is most concerned.

Kim Jong-un thanked Xi for his positive attitude. He said he would maintain peace and stability on the peninsula and create a favorable external environment for the development of the DPRK. In addition, North Korea has repeatedly expressed its position on the Hong Kong issue and firmly supports the Chinese party and government in safeguarding the "one country, two systems" principle, national sovereignty, and territorial integrity. In 2019, with the opportunity of celebrating the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries, practical cooperation between China and the DPRK in 8 fields including agriculture, tourism, education, and health, has been further developed. This year is also the 60th anniversary of China’s resistance to US aggression and aid to North Korea. The atmosphere of traditional friendly cooperation between China and North Korea is booming.

At the same time, with the failure of the Hanoi summit, North Korea has repeatedly tested short-range missiles. The US continues to exert extreme pressure on it, and South Korea has found it difficult to carry out economic cooperation with the North alone. Since the end of 2019, the North Korean government has clearly signaled that it will turn tough. The outbreak of COVID-19 may delay implementation of the tough line, but the economic sanctions and the impact of the pandemic have added to the urgency of lifting external restrictions on development as soon as possible. Under the background of increasingly fierce strategic and economic competition between China and the US, on the one hand, North Korea is more inclined to take advantage of the political, economic, and strategic support from China toward a brinkmanship policy. On the other hand, due to the serious lack of strategic mutual trust between China and the US, Washington is unlikely to rely on Beijing again on the DPRK nuclear issue, let alone give China the leverage of persuading and promoting conversation. So the possibility of cooperation between China and the US on the nuclear issue is further reduced, while the possibility of crisis on the peninsula is rising again.

Conclusion

After the Cold War, due to sharp differences in core interests, bilateral relations between China and the DPRK stayed cold for a long time. China wanted to fit into the international community, establish strategic partnerships with developed countries such as the United States, Japan, and South Korea, and act as a responsible major power in international affairs, creating a favorable external environment for domestic development. In contrast, due to the loss of China and the Soviet Union as allies, coupled with hostility and pressure from the United States and its allies, North Korea, from China’s perspective, was forced to become a nuclear weapon-possessing country, further isolating itself from the international system. However, in spite of the overall coldness of their bilateral relations, during three periods—1999-2001, 2010-2012, and 2018-2019—bilateral relations heated up quickly. In fact, China-DPRK relations depended largely on the ups and downs in China-US relations. During these three periods, China and the DPRK quickly formed an "anti-US front" on major international and regional issues. However, China-US relations twice rebounded, and differences were mitigated by common interests. Once relations recovered, both sides coordinated their positions on the DPRK nuclear issue and jointly exerted pressure on the DPRK, which again froze China-DPRK relations. China-DPRK relations have been deeply affected by changes in China-US relations.

Although highlighting the interaction of the triangular relationship between China, the US, and North Korea or the impact of the China-US bilateral relationship on the peninsular situation may to some extent ignore other explanatory factors, this is how it works. From the perspective of the Northeast Asian regional structure, Russia and Japan were obviously marginal players among the countries participating in the Six-Party Talks. They were concerned about the situation on the peninsula, but they were never players in the core circle. The essence of the North Korean nuclear issue is the reunification of the peninsula, so North Korea and South Korea are key players naturally. However, due to the long-term existence of the US-South Korea alliance, South Korea’s political and diplomatic independence is in doubt, and its military and security are almost entirely dependent on the United States. From the easing of relations between the two Koreas in 2018 to another deadlock in 2019, to the bombing of the liaison office in June this year, the fundamental reason is that North Korea is extremely dissatisfied with Seoul’s policy towards it. Especially after the breakdown of the Hanoi negotiations, South Korea followed the US policy towards North Korea, failing to restart economic projects, and cooperation and exchanges were stagnant. Compared with South Korea, North Korea is economically dependent on China, but politically and militarily, the relationship is no longer an alliance. Today, North Korea not only has nuclear weapons, but also its economic reform and development are proceeding steadily. Its national strategy will only become more and more independent.

With the increasingly fierce strategic competition between China and the US, maintaining the strategic stability of the Korean Peninsula and the multilateral balance of power in Northeast Asia will be one of China’s greatest long-term interests. Nuclear proliferation has been an important factor in China-DPRK relations, but given that North Korea is unlikely to give up its possessions, this negative factor is likely to be removed. Some argue that the deadlock on the DPRK nuclear issue will further increase the risk of nuclear proliferation and trigger a chain reaction in Northeast Asia; but in fact, in recent years, it is the US and Russia that are constantly upgrading their nuclear arsenals. Meanwhile, others believe the limited nuclear arsenal of North Korea and the nuclear potential of Japan and South Korea balance each other and help avoid further escalation. Therefore, the prospect of a peaceful settlement of the North Korean nuclear issue is even bleaker as the strategic competition between China and the United States continues to intensify.

Appendix I: The exchange of visits between Chinese and DPRK leaders based on data from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676404/sbgx_676408/.

Appendix II: The exchange of visits between Chinese and DPRK high-level delegations based on data from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China and International Department, Central Committee of CPC

Note: Due to the socialist political system, the party to party exchange between the Communist Party of China and Korean Workers Party is an essential part of bilateral political relations. Even if the bilateral relations face tensions, the party to party exchange usually continues. That is why combing the data from both Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China and International Department, Central Committee of CPC, makes the curve smoother. The party delegation led by the politburo member is counted as 0.8 while led by the minister of the party department is counted as 0.5.

Source: The party to party exchanges database of International Department, Central Committee of CPC can be accessed at http://www.idcpc.org.cn/jwdt/2013_239/yz_240/.

Bibliography

“Building a Better Future for China-U.S. Cooperative Partnership,” People’s Daily Online, February 17, 2012, http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1024/17136224.html.

Chen Fengjun and Wang Chuanjian, 亚太大国与朝鲜半岛(Beijing, Peking University Press,2002).

“From a handshake across the Pacific to a cooperation across the Pacific: Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President have a meeting at Sunnylands,” People’s Daily, June 11, 2013,

http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/0611/c1001-21811791.html

“For friendship and peace—congratulate General Secretary Jiang Zemin on his successful visit to North Korea,” People’s Daily, September 6, 2001, http://www.chinanews.com/2001-09-06/26/119589.html.

Hong Sukhoon, “What Does North Korea Want from China? Understanding Pyongyang’s Policy Priorities toward Beijing,” The Korean Journal of International Studies 12:1 (2014), pp. 284-286.

Kim Chong Woo and Samir Puri, “Beyond the 2017 North Korea Crisis: Deterrence and Containment,” Asan Institute for Policy Studies 22 (2017), pp. 5-9.

Kim, Suk Hi, “Reasons for a Policy of Engagement with North Korea: The Role of China,” North Korea Review 13:1 (Spring 2017), pp. 90-91.

Ku Yangmo, “Transitory or Lingering Impact? The Legacies of the Cheonan Incident in Northeast Asia,” Asian Perspective 39:2 (April-June 2015), pp. 253-276.

“Li Keqiang holds talks with List of Premiers of North Korea Choe Yong-rim in Pyongyang,” The Chinese government’s website, October 23, 2011, http://www.gov.cn/ldhd/2011-10/23/content_1976547.htm.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676404/sbgx_676408/.

“North Korea Announces Suspension of Nuclear Test and Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Launch Test,” Xinhua, April 21, 2018, http://www.xinhuanet.com/mil/2018-04/22/c_129856062.htm.

Paul, T.V.,ed., Accommodating Rising Powers: Past, Present, and Future (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Pang Lian and Yang Xinyu, “从同盟到伙伴:中朝关系的历史演变,” 世界纵横,No.3, 2008, pp.84-88.

“President of the China Foreign Affairs Association: The situation has changed greatly and China’s influence on North Korea has been limited,” China Review News Service, June 17, 2009, http://www.crntt.com/crn-webapp/doc/docDetailCreate.jsp?coluid=9&kindid=4830&docid=100997943.

Ross, Robert, “The 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait Confrontation: Coercion, Credibility, and the Use of Force,” International Security 25:2 (2000), pp. 87-123.

Suettinger, Robert, Beyond Tiananmen: The politics of U.S.-China relations (1989-2000) (Washington, D.C: The Brookings Institution Press, 2003), pp. 515-523.

Shen Zhihua, ”破镜重圆:1965-1969年的中朝关系,” 华东师范大学学报(哲学社会版), No.4, 2016, pp.1-14.

Sun Zhe, ed., 后危机世界与中美战略竞逐 (Beijing: Current Affairs Press, 2011).

Tang Jiaxuan, “The common interests of China and the United States always outweigh differences,” china.com, September 22, 2001, http://www.china.com.cn/zhuanti2005/txt/2001-09/22/content_5060640.htm.

Tao Wenzhao, 中美关系史(第3卷)1972-2000 (Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2016), p. 358.

The White House, “National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” December 2017, pp. 2-3, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905-2.pdf (accessed March 1 2020).

Wang Junsheng, “冷战后中国的对朝政策——美国的解读与分歧,” 东北亚论坛,No.4, 2013, pp.19-27.

“Working Together to Usher in a Better Future for China-DPRK Relations: A State Visit by General Secretary Xi Jinping,” Xinhua, June 23,2019,

http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2019-06/23/c_1124658726.htm.

Wu Jianmin, 外交案例 (Beijing: Renmin University Press, 2007).

“Xi Jinping Holds Talks with Kim Jong-un,” Xinhua, March 28, 2018, http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2018-03/28/c_1122600292.htm.

“Xi Jinping Meets Workers’ Party of North Korea Chairman Kim Jong-un,” Xinhua, June 20, http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2019-06/21/c_1124656078.htm.

Zhang Weiqi, “Neither friend nor big brother: China’s role in North Korean foreign policy strategy,” Palgrave Communication4:16 (2018), pp. 1-6.

Zhang Xiaoming, “The Korean Peninsula and China’s National Security: Past, Present and Future,” Asian Perspective 26:3 (2002), pp. 131-144.

“Zhu Bangzao: Jiang Zemin visits North Korea to promote further development of bilateral relations,” China News Services, September 4, 2001, http://www.chinanews.com/2001-09-04/26/119235.html.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn