*The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not presented as those of the Congressional Research Service or the Library of Congress.

Like other countries in East Asia, Vietnam has had to cope with a changed strategic and economic environment forged by China’s rise and growing competition between China and Japan. Although Vietnam’s relationship with China is its most important, Vietnamese leaders have sought to hedge against becoming too dependent on and vulnerable to China by boosting relations with other powers, particularly the United States, Japan, and India. Notably, over the past several years, Vietnam and Japan have expanded their relationship beyond the economic sphere that previously had dominated. Pushed together by the two countries’ heightened sense of threat from China, Hanoi and Tokyo have accelerated their strategic cooperation.

The primary variable affecting the pace and extent of future Vietnam-Japan relations is the Vietnam-China relationship. The more intense the threat Vietnamese leaders feel from China’s actions, the more likely they are to pursue improved strategic relations with Japan. This was shown during the spring and summer of 2014, when longstanding tensions between Vietnam and China over competing territorial claims in the South China Sea flared after the state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) moved the Haiyang Shiyou 981 exploratory oil rig into waters claimed by both countries. Scores of Chinese ships, including some coast guard and naval vessels, reportedly entered the area escorting the rig. The crisis, which was defused in July when the rig was withdrawn, prompted Vietnamese officials to engage in a flurry of diplomacy with the United States and Japan, including the culmination of a long-discussed agreement by Japan to provide Vietnam with several naval patrol vessels, accompanied by hints that Tokyo would be selling or transferring more security-related hardware in the future.

There are, however, at least two factors inhibiting the development of Vietnam-Japan relations. The first is the pull factor that China exerts on Vietnamese foreign policy, both because of concerns about unduly upsetting Beijing and because of the sensitivity toward China on account of Vietnam’s political system. The second related brake is Vietnam’s proclivity to maintain an “equidistant” foreign policy, in which it does not lean far to any one side. This approach generally has served it well for the past quarter-century, but it is unclear whether that will continue to be the case if the “win-lose” competition between China and Japan in East Asia deepens. In particular, an intensification of the tensions between China and Japan—as well as between China and the United States—could strip away some of the insulation that has protected the Vietnam-Japan relationship thus far, subjecting it more to the careful calibrations that Vietnamese leaders have had to employ when debating their relationship with the United States.

Great power rivalry in Southeast Asia

Over the past four years, great power rivalries have intensified in Southeast Asia, with the primary competition being between the United States and China. But, since at least 2012, Japan has resurfaced as a significant player through its economic diplomacy and, more recently, its military diplomacy. In contrast to previous periods, when Japan sought to carve out a somewhat independent regional role, it has explicitly associated itself with US policy, aggressively boosting its capabilities to support US influence and expanding its security consultations and relations with Australia as well as the Philippines and Vietnam. Increasingly, the competition is occurring between China on the one hand, and the United States and Japan on the other, with the latter two building bridges to third countries and Beijing seeking to dissuade them from participating in any collective efforts to oppose China’s initiatives. Vietnam has become a significant player in this drama between China and the United States/Japan.

At least three factors have sparked the intensification of great power rivalries in Southeast Asia:

1.

2.

3.

Vietnam’s strategy: Push & pull factors

Vietnam is an example of the contradictory pushes and pulls being felt by Southeast Asian nations as they try to both react to and shape the new regional situation. On the one hand, its leaders have attempted to increase their leverage against what they perceive as a worrying increase in Chinese influence and territorial assertiveness by attempting to forge a unified ASEAN response and cultivating stronger relations with outside powers. On the other hand, wariness of provoking a stronger Chinese response has led Hanoi to take these steps cautiously and incrementally. Indeed, the state of the Sino-Vietnamese relationship appears to be the primary variable influencing the pace and scope of Vietnam’s partnerships with these other powers.

In many ways, this hedging strategy has been in place for nearly 30 years. Since the mid-to-late 1980s, Vietnamese leaders essentially have pursued a four-pronged national strategy: 1) focus on economic development through market-oriented reforms; 2) advance good relations with Southeast Asian neighbors that provide Vietnam with economic partners, diplomatic friends, and—through ASEAN—the institutional vehicle to promote its desire for middle-power influence; 3) deepen its relationship with China; and 4) simultaneously seek counterweights to Chinese ambition and influence by expanding relations with the United States, but also with other powers such as Japan and India.1

This strategic approach reflected a central lesson learned from the Cold War period: Hanoi’s interests were often ill-served by leaning on one external power and heavily towards one side in great power rivalries.2 In 1978, amidst deteriorating relations with China and after the failure of rapprochement attempts with the United States, Vietnam formed an alliance with the Soviet Union. Combined with its invasion of Cambodia that same year (in response to the communist Cambodian government’s incursions into its territory), Vietnam, in short order, found itself with few friends outside of Moscow. Its isolation played a role in the disastrous deterioration of its centrally-planned economy over the coming decade, a point that was brought home when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev began to cut back on Soviet patronage.

In response, Vietnamese leaders adopted the landmark Politburo Resolution no. 13 of May 1988, consolidated as doctrine three years later during the Seventh National Congress of the Vietnam Communist Party (VCP), which called for Vietnam to “diversify and multi-lateralize economic relations with all countries and economic organizations… and become the friend of all countries in the world community.”3 Turning away from reliance on the Soviet Union, it instead would follow an omni-directional foreign policy orientation, necessary to secure economic development. This maximized Vietnam’s space for maneuver by cultivating as many interdependent ties as possible, a “clumping bamboo” strategy—behaving like bamboo that will easily fall when standing alone, but will remain standing strong when growing in clumps.4

Vietnam’s governing structure

In Vietnam, the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) sets the general direction for policy, while the details of implementation generally are left to the four lesser pillars of the Vietnamese polity: the state bureaucracy, the legislature (the National Assembly), the Vietnamese People’s Army (VPA), and the officially sanctioned associations and organizations that exist under the Vietnamese Fatherland Front umbrella. The Party’s major decision-making bodies are the Central Committee, which has 175 members, and the Politburo, which has 16 members.

Over the ensuing years, Vietnam withdrew its forces from Cambodia, repaired its relations with Beijing and the United States, joined ASEAN, and expanded contacts with virtually all countries. Starting in 2001, it expanded its approach by pursuing “strategic partnerships” and “comprehensive partnerships” with a variety of countries that its leaders deemed important to achieving the goal of integrating with the global community. (See Table 1) Ideologically, this evolution in diplomatic strategy was made possible, among other steps, by guidance adopted in 2003 by the VCP Central Committee’s Eighth Plenum, which directed Vietnam to “cooperate” with outside powers for mutual benefit when interests converge” and to “struggle” with them when they challenge Vietnam’s national interests, such as one-party rule and human rights.5

Table 1. Partial List of Vietnam’s Strategic and Comprehensive Partnerships

| Country | Date |

|---|---|

| Russia | 2001 |

| Japan | 2006 |

| India | 2007 |

| China | 2008 |

| Australia* | 2009 |

| Venezuela* | 2008 |

| New Zealand* | 2009 |

| South Korea | 2009 |

| Spain | 2009 |

| United Kingdom | 2010 |

| Germany | 2011 |

| Denmark* | 2013 |

| France | 2013 |

| Indonesia | 2013 |

| Italy | 2013 |

| Singapore | 2013 |

| Thailand | 2013 |

| Ukraine* | 2013 |

| United States* | 2013 |

* Indicates comprehensive partnership.Sources: Huong Le Thu, “Bumper Harvest in 2013 for Vietnamese Diplomacy,” ISEAS Perspective, 5; Carl Thayer, “Vietnam on the Road to Global Integration: Forging Strategic Partnerships Through International Security Cooperation,” Oral Presentation to the Opening Plenary Session Fourth International Vietnam Studies Conference, Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences and Vietnam National University, Hanoi, November 26-30, 2012; and various news sources.

Vietnam’s strategy has worked best when tensions with its neighbors are not inflamed and great power rivalries in Southeast Asia remained muted, especially when it and China are able to insulate their territorial tensions from other aspects of the relationship and, likewise, when a zero-sum competition in the region is kept to a minimum. However, the contradictions in Vietnam’s so-called “omni-directional” approach are many and appear to have become increasingly difficult to manage as China has become more assertive and as a cold war-type environment has settled on the region.

Sino-Vietnamese relations

Over the past decade, Sino-Vietnam relations have followed seemingly contradictory trends, and China acts as both a push and a pull factor on Vietnam’s relations with other countries.6 This dynamic of ambivalent Sino-Vietnamese relations is nothing new. They have a long history of struggle and cooperation, and Vietnamese have tended to view China as both a role model and a potential threat. China ruled Vietnam for over a thousand years until Vietnam successfully fought for its independence in the year 939. China ruled Vietnam from 1407 to 1428, until another rebellion drove it out. Despite this restoration of independence, Ming China continued to exert a profound influence on Vietnamese culture and governance, particularly among the elite.

After China’s Communists defeated Chinese Nationalist forces in 1949, Beijing was an important patron for Vietnamese Communists who fought first against French colonial rule and then against South Vietnam and the United States; however, even then relations often were strained. Many Vietnamese Communists felt betrayed whenever the PRC appeared to pursue its interests at their expense. Long-repressed tensions resurfaced in the 1970s, coinciding with the US military withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973 and communist Vietnamese forces’ defeat of the US-backed Republic of Vietnam in 1975. China seized the Paracel Islands (which it calls the Xisha Islands) from Vietnam in 1974, and it sought to limit Vietnamese influence in Cambodia, which also had territorial disputes with Vietnam. In early 1979, following Vietnam’s alliance with the Soviet Union and invasion of Cambodia, China attacked Vietnam for a two-month period, in a brief, but bloody, border conflict, during which the two sides severed relations. Vietnamese forces exacted an unexpected heavy toll on Chinese troops. Military skirmishes continued during the 1980s across their disputed land border.

Hanoi’s move to repair relations resulted in rapid normalization of official and party-to-party relations in 1990. Thereafter, efforts continued to maintain good overall relations with its northern neighbor, despite ongoing tensions over competing claims in the South China Sea. Particularly notable were a 1999 agreement to demarcate the countries’ land border and a demarcation and fishing cooperation agreement for the Gulf of Tonkin a year later. In 2008, Vietnam and China formed a strategic partnership, which was upgraded to a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership” the following year.

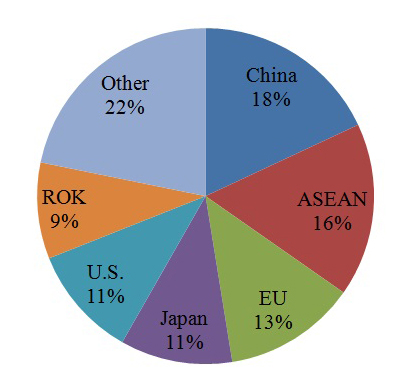

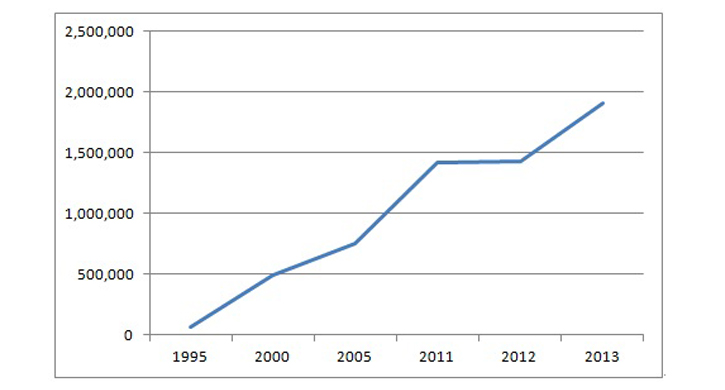

By the time these partnership arrangements were formalized, China had re-solidified its status as Vietnam’s most important bilateral partner. Maintaining stability and friendship with its northern neighbor is critical for Vietnam’s economic development and security. China has emerged as Vietnam’s largest trading partner (see Figure 1), albeit one with which Vietnam runs a large (and rising) trade deficit.7 Tourism has mushroomed, with nearly two million—over a quarter of all foreign visitors—Chinese visiting Vietnam in 2013, more than double the number in 2005. (see Figure 2) China is also an ideological bedfellow, as well as a role model for allowing more market forces without threatening the Communist Party’s dominance. Vietnam and China see most global issues through the same lens, and during Vietnam’s two-year stint as a non-permanent member of the Security Council from 2008-2009, they generally adopted similar positions. Hosting Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi in 2008, Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung remarked that “the mountains and rivers of Vietnam and China are adjacent, cultures similar, ideologies shared, and destinies interrelated.”8 Until the oil rig crisis of 2014, many Vietnamese officials said that aside from their South China Sea disputes, bilateral relations were proceeding smoothly.

Figure 1. Vietnam’s Major Trading Partners, 2012

Source: General Statistics Office of Vietnam

Moreover, the VCP and CCP have maintained strong connections, including over the past five years when bilateral tensions have mounted over competing South China Sea claims. These party-to-party ties provide a vehicle for managing relations that Vietnam lacks with Japan or the United States, depriving both countries of a window into its innermost decision-making circles.

Figure 2. Foreign Visitors to Vietnam from China

Source: Vietnam General Statistics Office, reprinted by

Vietnam National Administration of Tourism

Strategic dynamics

Despite these expanding ties, Vietnam’s historical ambivalence and suspicions of China have increased due to concerns that China’s expanding influence in Southeast Asia is having a negative effect on Vietnam. The most significant of these have been the two countries’ unresolved maritime disputes in the South China Sea. Even before the 2014 oil rig crisis, China had taken a number of actions to assert its claims since 2007, including reportedly warning Western energy companies not to work with Vietnam to explore or drill in disputed waters, announcing plans to develop disputed islands as tourist destinations, and cutting sonar cables trailed by seismic exploration vessels working in disputed waters for PetroVietnam. For its part, Vietnam has stepped up its presence in the disputed areas; since 2005, it has been active in soliciting bids for the exploration and development of offshore oil and gas blocks off its central coast and in areas disputed with China, and for Vietnam’s last two Five-Year Plans, which covered the years 2006-2011 and 2011-2016 and placed a strong emphasis on offshore energy development. Both Vietnam and China have seized fishing boats and harassed ships operating in the disputed waters.

In keeping with their belief in the need to struggle as well as cooperate, concerns over perceived Chinese encroachment have led Vietnamese leaders to take steps to lessen their vulnerability to Chinese influence. According to Vietnam’s most recent Defense Ministry White paper, released in 2009, Vietnam’s defense budget increased by nearly 70 percent between 2005 and 2008.9 In a move widely interpreted as related to increased maritime tensions, Vietnam in 2009 signed contracts to purchase billions of dollars of new military equipment from Russia, including six Kilo-class submarines that have begun to arrive.

In 2010, Vietnam used its one-year term ASEAN chair to internationalize the disputes, in the hopes it would force China to negotiate in a multilateral setting, rather than Beijing’s preferred bilateral manner. The Vietnamese campaign targeted the United States and Japan; a new level of cooperation was seen during the July 2010 ARF meeting in Hanoi. Secretary of State Clinton, Vietnamese Foreign Minister Khiem, Japanese Foreign Minister Okada Katsuya and counterparts from nine other nations, including several ASEAN members, raised the issue of the South China Sea. Clinton said that freedom of navigation on the sea is a US “national interest” and that the United States opposes the use or threat of force by any claimant. She added that “legitimate claims to maritime space in the South China Sea should be derived solely from legitimate claims to land features,” which many interpreted as an attack on the basis for China’s claims to the entire sea.10 Though Okada did not go as far as her, he argued that the South China Sea disputes were best handled in a multilateral setting.11 Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi reportedly verbally attacked those who raised the issue during the meeting.12

Since 2010, Vietnam has intensified its multi-pronged strategy toward the South China Sea disputes. As Table 1 shows, it engaged in a flurry of partnership diplomacy, adding the United States and several important ASEAN countries. It also increased its push within ASEAN to negotiate a multilateral code-of-conduct with China, and cooperation with the Philippines, another claimant in the South China Sea disputes. A key part of its clumping bamboo strategy has been to deepen military and strategic cooperation and information-sharing with Japan, e.g., prior to the 2014 oil rig crisis, Vietnam reportedly proposed convening a trilateral security dialogue with the United States and Japan.13

Vietnam has simultaneously sought to avoid moving too fast to unduly provoke China. After the 2010 flare-up of South China Sea tensions, e.g., it sought to improve overall relations with China both by managing their maritime dispute and by compartmentalizing it. Between 2011 and May 2014, Hanoi and Beijing expanded high-level ties, signed an Agreement on Basic Principles Guiding the Settlement of Maritime Issues, and negotiated a 2013 bilateral agreement creating working groups to discuss joint development in the disputed areas and a hotline to deal with fishery incidents.

Hanoi’s response to CNOOC’s H.S. 981 deployment epitomizes the tightrope that Vietnamese leaders have attempted to walk between China and its rivals. Almost immediately after the rig was moved into position, Vietnamese patrol boats and fishing boats entered the same waters, leading to a number of collisions. In the initial weeks of the crisis, China reportedly refused to hold high-level bilateral meetings unless Vietnam first agreed to stop harassing the rig, drop its sovereignty claims over the Paracels, abandon plans to pursue legal action against China, and stop trying to involve third parties, such as the United States and Japan. Instead, Vietnam began making preparations for initiating legal action against China for allegedly violating the United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS),14 and its diplomats aggressively reached out to partners around the globe for diplomatic support.15 It, however, dropped many of its more confrontational plans—such as proceeding with legal actions—once China appeared to back down from some of its other preconditions for a meeting. Over the early summer, the crisis was gradually defused, and in July, CNOOC withdrew the rig weeks earlier than scheduled, announcing that it had completed its operations and needed to move the rig to avoid an approaching typhoon. In late August, VCP Politburo Standing Committee member Le Hong Anh, a special envoy of Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, traveled to Beijing to meet with his counterparts, including Xi Jinping. The two sides agreed “…to effectively control sea disputes and not act to complicate or expand disputes…” in the South China Sea.16 At a minimum, Hanoi and Beijing appeared to have halted the downslide in their bilateral relationship.

Domestic dynamics

The HS981 crisis revealed how sensitive Sino-Vietnamese relations are in Vietnamese domestic politics. In the days after the rig’s deployment, protests erupted inside Vietnam, culminating in Vietnam’s worst reported violent unrest in years. Workers in industrial areas on the outskirts of Ho Chi Minh City and in central Vietnam rioted, damaging Chinese, Taiwanese, and other foreign-owned factories and killing at least four foreigners, including at least two Chinese, and wounding scores of others.17 The riots showed how relations with China increasingly have become a feature of domestic politics.18 Leaders have become exceedingly cautious about handling high-profile matters involving China, in part because the leadership often is divided about where Vietnam should be on the struggle-cooperation continuum. These internal battles tend to surface whenever relations with China become tense, as was seen during the 2014 oil rig crisis, when the Politburo reportedly engaged in heated debates over whether to take more confrontational measures, such as initiating international arbitration proceedings against the rig’s deployment and engaging in more overt cooperation with the United States and possibly other outside countries. Reporting on these internal discussions has associated some of Vietnam’s more ideological conservative leaders, such as President Nguyen Phu Trong, who are believed to have a greater affinity toward China, with the less confrontational camp.19

No other bilateral relationship triggers as much raw emotions at the popular level in Vietnam. Over the past decade, growing numbers of Vietnamese have become angered by what they see as their leaders’ overly solicitous attitudes toward China. Whereas the leadership appears to be debating how best to uphold the status quo with China, voices at the popular level tend to be more strident. As one report puts it, “everywhere in Vietnam, one hears the phrase thoát Trung, escape from China’s orbit.”20 The frustrations have focused on Vietnam’s territorial disputes with China and on China’s increased economic presence in Vietnam. These concerns morphed together in the May 2014 riots that followed the oil rig deployment; although there is evidence that the rioters were motivated in part by longstanding labor grievances against a range of foreign-owned factories, it appears that anti-Chinese sentiments, at a minimum, triggered the outburst.21

The potency of anti-Chinese sentiment can be seen in the way the Vietnamese government has handled it. Although leaders occasionally allow anti-Chinese protests, in general they attempt to suppress them, particularly because of concerns they will quickly morph into criticisms of Vietnamese government policy. Many of the bloggers and lawyers whom Vietnamese authorities have arrested or harassed over the past five years have criticized Vietnam’s policy toward China and/or have links to pro-democracy activist groups.

Vietnam-Japan relations

Vietnam’s relationship with Japan appears to be both less significant and less sensitive than its relationships with China and the United States. While no VCP general-secretary has ever visited the United States, two have traveled to Japan: Do Muoi in 1995 and Nong Duc Manh in 2002.22 When asked about the prospects of such a trip to the United States, government and party officials have said that concerns about upsetting China are among the reasons for the high-level caution.23

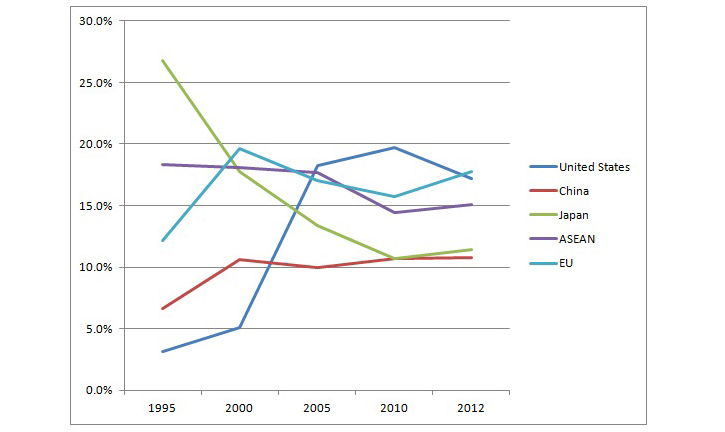

Figure 3. Shares of Vietnam’s Exports with Top Trading Partners, Selected Years

Source: General Statistics Office of Vietnam

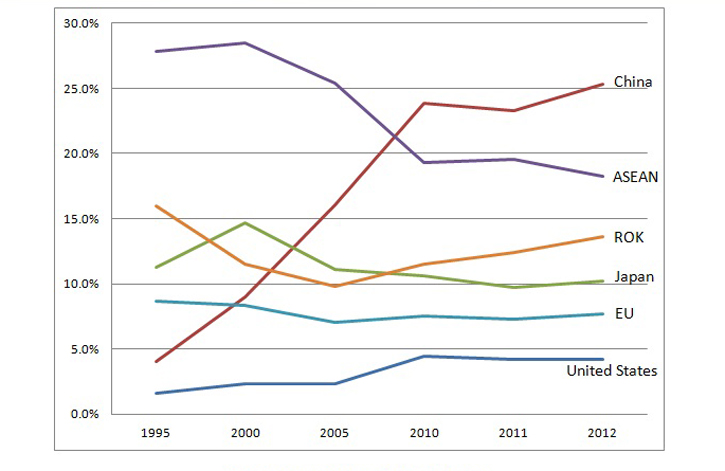

Until recently, Vietnam-Japan relations have tended to be dominated by economic matters. For years after Vietnam launched its doi moi economic reforms in 1986, Japan was its most important trading partner, e.g., in 2000, it was the destination of nearly 18 percent of exports—nearly double the share of the second largest market, China. (see Figure 3) That same year, Japan was the source of nearly 15 percent of Vietnam’s imports, compared with 9 percent for China. (see Figure 4) However, this shifted rapidly with China’s entry into the WTO and Vietnam’s normalization of economic relations with the world’s major markets, particularly the United States.24 By 2005, the United States had surpassed Japan as Vietnam’s largest export market. Meanwhile, first China in the middle of the decade and then South Korea by the end passed Japan on the list of its sources of imports.

Figure 4. Shares of Vietnam’s Imports from Major Trading Partners, Selected Years

Source: General Statistics Office of Vietnam

Even after being eclipsed by China economically, Japan’s primary importance continued to be in the commercial and financial spheres. For nearly two decades, Japan has been Vietnam’s largest bilateral aid donor, a status that it retained despite periodic suspensions of assistance due to corruption surrounding Japanese aid projects in Vietnam. In 2008, the two countries signed Japan’s equivalent of an FTA (an EPA or economic partnership agreement) and three years later, Japan was the first G7 country to recognize Vietnam as a “market economy,” which provides significant commercial benefits to Vietnamese exporters. Japan also expanded science cooperation, including orchestrating a Japanese consortium’s successful bid to build what is slated to be Vietnam’s second nuclear power plant in the 2020s. In 2013, Japanese companies became Vietnam’s largest source of FDI, according to the Vietnamese government.

As part of both countries’ efforts to hedge against China’s rising power, bilateral cooperation on strategic matters gradually increased, e.g., in 2010, they began annual “2+2” dialogues among senior foreign and defense ministry officials, and in 2013, a MOU on defense cooperation was signed, focusing on increasing cooperation in the areas of humanitarian aid and disaster relief. Also in 2011, Phung Quang Thanh became the first defense minister to visit Japan in 13 years.25 In 2013, the first vice-ministerial defense talks were held, and Japan announced it would begin providing non-lethal military assistance.26 Since at least the mid-2000s, Vietnam has backed Japan’s bid to become a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, a step China has emphatically opposed. However, such cooperation often appeared to be downplayed. For instance, although Foreign Minister Okada Katsuya joined a coalition of countries criticizing China’s actions at the July 2010 ARF meeting, an October 2010 joint statement between prime ministers Dung and Kan Naoto made no mention of maritime disputes. The statement, issued at the end of Kan’s visit to Vietnam, occurred weeks after a major flare-up in Japan’s territorial dispute with China over the Senkaku/Diayou islets, perhaps indicating an unwillingness by one or both country to rile Beijing.27

In contrast, by early 2014, neither country hesitated to mention maritime cooperation or maritime disputes. Weeks before CNOOC deployed its oil rig to the South China Sea, a joint statement announcing the two sides’ agreement to upgrade relations to an “extensive strategic partnership” prominently featured defense and maritime cooperation near the top of the list of 69 items.28 In August, while visiting Hanoi, Foreign Minister Kishida Fumio announced that Tokyo would provide six used non-combatant patrol ships and “related equipment,” reportedly radar, “for the enhancement of maritime law-enforcement capabilities of Vietnam.” The two sides agreed to “accelerate” ongoing discussions of Japan’s provision of new patrol vessels to Vietnam.29 So far, China’s official public reaction to the deal appears to have been muted. Japanese ship assistance had been discussed at least since December, during Dung’s visit to Japan.

At least two changes account for the increased Vietnam-Japan strategic cooperation. First, the two increasingly see a convergence of interests on maritime issues. Notwithstanding improvements in Vietnam-China relations in 2013, as well as China’s decision to countenance multilateral code of conduct talks with ASEAN, Vietnamese leaders appear to have perceived the strategic environment as continuing to deteriorate, leading them to deepen their cooperation with potential balancers such as Japan, the United States (with which Vietnam signed a comprehensive partnership in 2013), and India. According to a number of sources, the Haiyang 981 deployment only accentuated distrust toward China.30 Increased Chinese assertiveness over the Senkakus/Diaoyu led Japanese leaders increasingly to see the South China and East China sea disputes as part of the same phenomenon.31

Second, the changing power balance in East Asia has led Japanese leaders to expand their network of partners beyond Japan’s US ally. In particular, the growing threat perception from China prompted Japan to vastly increase its defense diplomacy, an area that Japan had almost entirely eschewed since the end of World War II. As Celine Pajon has documented, the process began during the DPJ government, which relaxed Japan’s ban on military exports, increased security-oriented ODA, and initiated a new military assistance program.32 Abe has dramatically expanded Japanese defense diplomacy and involvement in Southeast Asia security matters. In his first year in office, Abe visited all ten ASEAN countries, and chose Vietnam to be the first overseas visit. Under Abe, Japan also has increased security coordination with Australia and the Philippines, including an agreement to send naval patrol vessels to Manila. The Abe government’s relaxation of Japan’s longtime restrictions on arms exports and his government’s historic decision in July 2014 to ease Japan’s ban on participating in collective self-defense (CSD) activities could open the door to sales of lethal defense articles to and greater military cooperation with Southeast Asian countries.33 One goal appears to be to obtain support from East Asian countries for this decision as the Japanese Diet undergoes the process of debating legislation to implement it. Speaking at a press conference two days after the Abe Cabinet announced its CSD decision, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Le Hai Binh expressed cautious if ambiguous support, reportedly stating, “Japan, as an influential country, would contribute to regional peace and stability.”34

Unlike China, Japan triggers few, if any, sensitivities inside Vietnam. Improving relations with Japan also has been less controversial than doing so with the United States. This is not only because of the legacy of the Vietnam War. Perhaps more important, Vietnamese conservatives suspect that Washington is trying to undermine the VCP’s monopoly on power; human rights issues occupy a prominent place in the US relationship. In contrast, Japanese leaders rarely, if ever, criticize Vietnam’s human rights record. Improving relations with Japan does not face the same domestic constraints as with China or the United States.

Conclusion

Over the past several years, shared perceptions of a growing challenge from China have pushed Vietnam and Japan to establish and expand cooperation in the security sphere. If China continues to act in ways that leaders believe are infringing on their sovereignty, Hanoi and Tokyo’s interests are likely to further converge. We then can expect more and deeper cooperation, which perhaps would include overt trilateral and/or quadrilateral cooperation with the United States and/or the Philippines on maritime security.

China’s gravitational presence, however, exerts considerable force on Vietnam that acts to moderate Hanoi’s behavior. For economic, ideological, strategic, and geographic reasons, Beijing remains Hanoi’s most important partner, and Vietnamese leaders must calculate how China will react to any large-scale moves. Vietnam-Japan relations thus far appear to be somewhat insulated from these pull factors. e.g., Vietnam formed a strategic partnership with Japan before doing so with China. However, if Sino-Japanese tensions escalate in the years to come and are not accompanied by an acute break between Hanoi and Beijing, Vietnam’s outreach to Japan may become more cautious as it strives to maintain a balance between its clumping bamboo and omni-directional diplomatic strategies.

Thus, the future course of Vietnam-Japan relations is likely to be highly dependent on China’s behavior. The more heavy-handed China’s assertiveness is from the Vietnamese and Japanese points of view, the more rapidly the two sides will deepen their strategic relationship and perhaps form a de facto link to the US alliance system. If China and Vietnam are able to contain their maritime disputes, it is likely that Vietnam will continue its current pattern of slowly building its capacities through incrementally expanding its relationship with Japan, while simultaneously avoiding the most overt forms of cooperation that could trigger a Chinese counter-response. In either case, short of the outbreak of military conflict with China, Vietnam is unlikely to abandon is non-alignment policy by pursuing a full-throttle counter-balancing strategy against China. Rather, Vietnam’s use of Japan as a hedge is likely to be of a softer variety.

1. Adapted from Marvin Ott, “The Future of US-Vietnam Relations” (Paper presented at The Future of Relations Between Vietnam and the United States, SAIS, Washington, DC, October 2-3, 2003).

2. Carlyle Thayer, “Strategic Posture Review: Vietnam,” World Politics Review, no. 15 (January, 2013).

3. Ibid.

4. Thuy T. Do, “Is Vietnam’s Bamboo Diplomacy Threatened by Pandas?” East Asia Forum, April 3, 2014.

5. The eighth plenum’s reinterpretation is summarized as follows: “With the objects of struggle, we can find areas for cooperation; with the partners, there exist interests that are contradictory and different from those of ours. We should be aware of these, thus overcoming the two tendencies, namely lacking vigilance and showing rigidity in our perception, design, and implementation of specific policies.” Carlyle Thayer, “Upholding State Sovereignty through Global Integration” (Paper presented to Workshop on “Vietnam, East Asia & Beyond,” Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong Hong Kong, December 11-12, 2008).

6. Thuy T. Do, “Is Vietnam’s Bamboo Diplomacy Threatened by Pandas?”

7. In 2013, Vietnam ran a deficit of about 23 billion dollars with China, a 50 percent increase since 2010. Since 2009, Chinese imports have represented around a quarter of Vietnam’s total imports by value, compared to less than 10 percent a decade earlier.

8. Thuy T. Do, “The Implementation of Vietnam-China Land Border Treaty,” S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Working Paper No. 173 (March 5, 2009): 4.

9. Vietnam, Ministry of Defense, White Paper, 2009, 38.

10. U.S. Department of State, “Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton Remarks at Press Availability,” National Convention Center, Hanoi, Vietnam, July 23, 2010.

11. Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Press Conference by Minister for Foreign Affairs Katsuya Okada,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs Press Conference Room, Tokyo, July 27, 2010.

12. John Pomfret, “U.S. Takes a Tougher Tone with China,” The Washington Post, July 30, 2010.

13. Carlyle Thayer, “Vietnam Mulling New Strategies to Deter China: What is Vietnam’s strategy for resisting Chinese coercion?” The Diplomat, May 28, 2014.

14. In Manila in May, Vietnam’s prime minister wrote to Reuters that his government was “considering various defense options, including legal actions in accordance with international law.” Rosemarie Francisco and Manuel Mogato, “Vietnam PM says considering legal action against China over disputed waters,” Reuters, May 22, 2014.

15. Hai Minh, “Extensive Activities To Protect National Sovereignty,” Vietnamese Government Web Portal, June 2, 2014.

16. Vietnam Foreign Ministry, “Vietnam, China Agree to Restore, Develop Ties,” August 28, 2014.

17. Shortly before Le Hong Anh’s trip to Beijing, Vietnam promised to compensate the Chinese workers and managers who were victims of the riots.

18. Zachary Abuza, “Vietnam buckles under Chinese pressure,” Asia Times, July 29, 2014.

19. For three perspectives on internal debates over how to deal with the oil rig crisis, see Zachary Abuza, “Vietnam buckles under Chinese pressure,” Asia Times, July 29, 2014; Alexander Vuving, “Did China Blink in the South China Sea?” The National Interest, July 27, 2014; and Carlyle Thayer, “Vietnam, China and the Oil Rig Crisis: Who Blinked?” The Diplomat, August 04, 2014.

20. ISEAS Monitor – Vietnam,” Issue 2014, no. 5 (September 1, 2014).

21. Patrick Boehler, “Just 14 factories targeted in Vietnam’s anti-China protests belonged to mainland Chinese,” South China Morning Post, updated May 20, 2014; Joshua Kurlantzick, “Vietnam Protests: More Than Just Anti-China Sentiment,” Asia Unbound blog, May 15, 2014, http://blogs.cfr.org/asia; Eva Dou and Richard C. Paddock, “Behind Vietnam’s Anti-China Riots: A Tinderbox of Wider Grievances.” Wall Street Journal, June 17, 2014.

22. Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affaris, “Japan-Vietnam Relations (Basic Data),” July 2012.

23. Author’s interviews in 2002, 2005, and 2012.

24. In 2001, Vietnam and the United States extended normal trade relations (NTR) status, also known as most-favored nation (MFN) status, to one another, significantly lowering tariffs on most products from the other country.

25. Japanese Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan 2013, 264.

26. Martin Fackler, “Japan is Flexing Its Military Muscle to Counter a Rising China,” New York Times, November 26, 2012.

27. Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Japan-Vietnam Joint Statement on the Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity in Asia,” October 31, 2010.

28. Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Vietnam, Japan Lift Bilateral Relations to New Height,” paragraphs 6-9, March 19, 2014.

29. Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Minister for Foreign Affairs Fumio Kishida’s Visit to Vietnam,” August 2, 2014.

30. Carlyle Thayer, “Vietnam’s East Sea Strategy and China-Vietnam Relations” (Paper delivered to the 2nd International Conference on China’s Maritime Strategy, Institute of Global and Public Affairs and the Shanghai Maritime Strategy Research Center, University of Macau, September 19-20, 2014).

31. As Abe said in a speech that was intended for delivery in Jakarta in January 2013, “Japan’s national interest lies eternally in keeping Asia’s seas unequivocally open, free, and peaceful—in maintaining them as the commons for all the people in the world, where the rule of law is fully realized…In light of our geographic circumstances, the two objectives are natural and fundamental imperatives for Japan, a nation surrounded by ocean and deriving sustenance from those oceans—a nation that views the safety of the seas as its own safety.” The Bounty of the Open Sea: Five New Principles for Japanese Diplomacy,” January 18, 2013. A year later, he and President Sang issued a joint statement saying, “…Mindful of air and maritime linkages between Vietnam and Japan in the region, Prime Minster Shinzo Abe stressed that any unilateral and coercive action to challenge peace and stability should not be overlooked. The two sides affirmed that peace and stability at sea were in the common interest of both countries as well as of the international community. They also shared the position that all relevant parties should comply with international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). They concurred on the importance of maintaining maritime security and safety, upholding the freedom of the high seas including the freedom of navigation and overflight and unimpeded commerce, and ensuring self-restraint and the resolution of disputes by peaceful means in accordance with universally recognized principles of international law including UNCLOS. They also shared the view that Code of Conduct (COC) in South China Sea should be concluded at an early date.” Vietnamese Foreign Ministry, “Vietnam, Japan Lift Bilateral Relations to New Height,” March 19, 2014.

32. Celine Pajon, “Japan and the South China Sea,” Institut Français des Relations Internationales Center for Asia Studies, January 2013.

33. Celine Pajon, “Japan’s ‘Smart’ Strategic Engagement in Southeast Asia,” The Asan Forum, December 06, 2013.

34. VOVWorld, “World Community Continues to Support Vietnam in the East Sea Issue,” July 3, 2014. Zachary Abuza writes that during internal party debates over responding to the HS981 deployment, some Vietnamese leaders pushed for a more explicit backing of Abe’s collective self-defense move. Zachary Abuza, “Vietnam buckles under Chinese pressure,” Asia Times, July 29, 2014.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn