What Can the China Dream “Do” in the PRC?

Since Xi Jinping chose “The China Dream” (中国梦) as his signature slogan in late 2012, much has been written on the topic. By mid-2014, 8,249 articles with “China dream-Zhongguo meng” in the title had been published within the PRC, according to the CNKI China academic journals database. Indeed, the 2014 round of major social science research grant funding in China was dominated by large projects that explore Comrade Xi’s thought in terms of the China dream. The China dream is also a popular topic among English-language journalistic and think tank commentaries, and already has generated a few academic articles.

To mark the two year anniversary of Xi’s China dream speech on November 29, 2012, it is time to reconsider not only what the phrase means, but what it can do. Unfortunately most writing on the subject is dominated by commentaries that 1) seek to explain the correct definition of the true China Dream, and/or 2) offer normative opinions about what the author thinks the China dream could and should be.

This short essay aims to do something different. Rather than engage in a Kremlinological search for the true definition of Xi’s China dream, it seeks to put China dream discourse in a social and political context. As we will see, the China dream did not appear out of thin air, but is part of a broad discussion of Chinese values that is ongoing.

This discussion also suggests that the China dream is best understood not according to a singular correct definition, but as a series of debates about whether it is an individual, collective, or national dream; a civil or military dream; the China dream or the American dream, and so on. The point then is not just to explain the proper “meaning” of the China dream, but to see what this formulation (提法) “does” in Chinese politics: which people does it bring together, and which does it shut out; which policies does it justify, and which does it exclude from consideration. In this way, we can use the China dream discourse to get a sense the political direction of the PRC under the fifth generation leadership.

Social and Political Context

Reflecting on their country’s recent economic success, China’s policymakers and opinion-makers are now asking “what comes next?” How can the PRC convert its growing economic power into enduring political and cultural influence in Asia and around the world?

China dream discourse here is part of a broad and ongoing debate sparked by the moral crisis that China faces after three decades of economic reform and opening. In other words, China’s liberals, socialists, traditionalists, and militarists are all worried about the “values crisis” presented by what they call China’s new “money-worship” society. Intellectuals from across the political spectrum thus are engaged in what Chinese call “patriotic worrying” (忧患意识); they feel that it is their job to ponder the fate of the nation, and to find the correct formula to solve China’s problems.1

Over the past few years many Chinese intellectuals addressed the PRC’s moral crisis by asking “Where is China going?” In his first month as China’s leader, Xi Jinping addressed this question when he proposed the “China dream” as his vision of China’s future. Although it is easy to dismiss such slogans as propaganda, they are crucial in organizing thought and action in Chinese politics. It behooves us then to take the “China dream” slogan seriously, and to examine what it can tell us about how Chinese politics works under the new leadership.

China’s National Dream

According to China’s official State Language Commission, “The China Dream” was 2012’s “hottest word” (热词). This popularity is quite political, as is shown by the second hottest word—Diaoyu islands(钓鱼台)—which is the major diplomatic and military flashpoint between China and Japan. The China dream was so popular because on November 29, 2012, Xi Jinping declared to a television audience that his “China dream” is for the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”2 Over the following months, Xi repeated the China dream slogan in numerous speeches, and then in March 2013 in his first speech as president at the National People’s Congress Xi concluded that to “fulfill the China Dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, we must achieve a rich and powerful country, the revitalization of the nation, and the people’s happiness.”

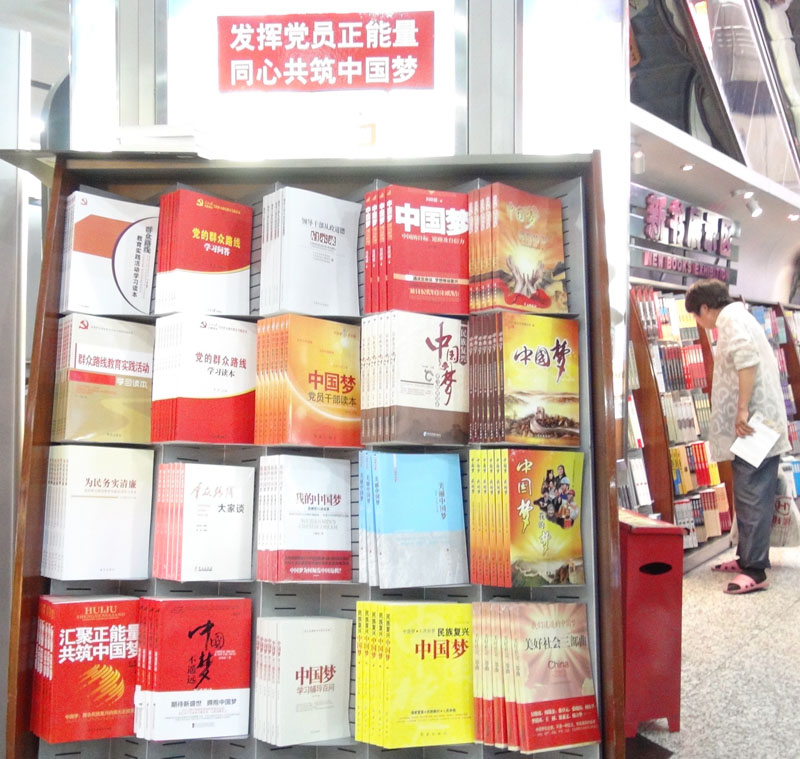

After the National People’s Congress, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Central Propaganda Department launched a multimedia campaign to guide the public’s correct understanding of the China dream. Numerous books were published on the topic, including: The China Dream: Selected Articles to Explain “The China Dream”; The China Dream: A Reader for Party Members and Cadres; The China Dream: 100 Questions for Study and Guidance; The China Dream is Our Dream; and Uphold the China Dream.3

These books are part of a well-organized propaganda campaign called “Educational Materials for Deepening the Understanding of the China Dream.” They were conspicuously promoted at China’s top bookstore, Beijing Book City, in a special bookcase designed to provide the “positive energy” to enable “party members to cooperatively build the China Dream together” (see Figure 1). As Frank Pieke explains, we need to take communist party education programs seriously because they mold the aspirations of China’s elite.4

Figure 1: The cadres’ book case at Beijing Book City, July 2013

© William A. Callahan

In December 2013, the communist party marked the one-year anniversary of the launch of China dream discourse by publishing a book of topical extracts from “Comrade Xi’s talks, speeches, discussions, articles and comments from November 15, 2012 to November 2, 2013—altogether 146 passages from over fifty important documents. Among them, some are published here for the first time.” The editors explain that the goal of the book is “to help cadres and the masses” around the country “to understand and grasp Comrade Xi Jinping’s important discourse on the China Dream.”

The general message of Xi’s book of selected quotations and the propaganda department’s guidebooks is that the China dream is “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Xi’s innovation on this Deng Xiaoping-era slogan is to declare that the China dream will be fulfilled according to the goals of his “two centuries” project. The “first century” will be the centennial of the founding of the CCP in 2021: the goal is for China to “complete the building of a moderately prosperous society” (小康社会), which includes doubling the 2010 GDP per capita income by 2020. The “second century” is the centennial of the founding of the PRC in 2049; its more vague long-term goal is for China to be “a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, civilized, and harmonious” by mid-century. As strategist Yan Xuetong explains, every Chinese leader since Sun Yatsen has talked about the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation; Xi Jinping is different because he talks “about the possibility to achieve it within our lifetime.”5

While liberals in China and abroad hoped that Xi Jinping would lead a political reform program, China dream discourse appeals to two illiberal alternatives: socialism and Chinese civilization. Although they seem to contradict each other, socialism and Chinese civilization are positioned as complementary discourses in Xi’s vision of China’s future that is both very modern and egalitarian, and very traditional with a hierarchical view of society. The values debate in China thus is generally framed as an East/West conflict in both its ideological and civilizational forms: i.e. socialism vs. capitalism, and Confucianism vs. liberal democracy.

The socialist aspect of the China dream is stressed, not surprisingly, in Xi’s talks at Politburo study sessions and in meetings with party cadre groups, model workers representatives, China Youth League activists and trade union leaders. Xi’s China dream is thus is not just a Chinese alternative to the West, but socialist alternative to liberal capitalist modernization. Alongside plans for a future socialist world, the glory and value of Chinese civilization is prominently discussed. Xi praises China’s history of 5,000 years of “superior civilization,” and enjoins Chinese people to “pass on our superior cultural tradition to the next generation,” which will be China’s contribution to world civilization.

Xi’s China dream is not part of a transition from communism to nationalism as many conclude. Rather it appeals to a combination of traditional China and socialist modernity: especially the China model of development and Confucian civilization. The role of political values in official China dream discourse is manifest in the current propaganda poster campaign that celebrates the China dream as a combination of traditional Chinese values like filial piety and thrift,6 and “core socialist values.” (see Figures 2 and 3)

Figure 2: Propaganda posters, Beijing, September 2014

© William A. Callahan

Figure 3: Propaganda poster, Shanghai, September 2014

© William A. Callahan

In addition to collected quotations, guidebooks, and posters, in April 2013 the propaganda committee of the Beijing branch of the CCP outlined a plan to promote the China dream through feature films, popular song contests, and even summer camps. The China Idol singing contest, which was broadcast on Shanghai’s DragonTV network from May to August 2013, is likely the result of a similar propaganda policy in that city: in Chinese the contest is called “The Voice of the China Dream” (中国梦之声). While China dream discourse generally combines socialism and Chinese tradition, the song contest shows the propaganda system’s own logistical innovations that use commercial entertainment to promote traditional Leninist messages of patriotic solidarity.

The China dream singing contest is interesting because it highlights an important tension in the propaganda campaign’s official message: is the China dream an individual dream or a national dream? “The Voice of the China Dream” suggests that it is an individual dream. American Idol/China Idol-type programs evoke the narrative of the “American dream”: with a little luck and talent, and a lot of hard work, you can achieve fabulous success. This China dream is also cosmopolitan: the winner of the contest sung a duet with American pop star Lionel Richie.

In 2013, many people in the PRC were talking about their individual dreams: the China dream of getting your “dream house” was a popular topic, as was the “entrepreneurial dream” and the “dream of the good life.” A sociologist in Beijing told me that to her 40-something generation the “China dream” was more modest: “A stable life. Not a fascinating life. A stable life with a person you love, with a job you like to do.”

The Southern Weekend (南方周末) newspaper was more ambitious in its January 2013 New Year’s editorial, “The China Dream, The Dream of Constitutionalism.” It called for legal limits on the power of the party-state, and argued that the quest for human dignity needs to go beyond economic prosperity: “Our dream today cannot possibly end with material things; we seek a spiritual wholeness as well. It cannot possibly end with national strength alone; it must include self-respect for every person. … We will continue to dream until every person, whether high official or peddler on the street, can live in dignity.” The editorial concluded that “the real ‘China Dream’ is a dream for freedom and constitutional government.”7

This is not the first time that Southern Weekend discussed the Chinese aspirations in terms of the China dream. Since 2010—i.e. two years before it became official—Southern Weekend has sponsored an annual “China Dreamer” awards ceremony that celebrates the achievements of Chinese diplomats, journalists, artists, and writers in a grand ceremony at Peking University. The first awardee was Lung Ying-tai, a scholar-activist-official from Taiwan, who described her China dream in terms of the “power of civility”—as opposed to the power of coercion and censorship.8

After the China dream phrase became official, there was a debate within Southern Weekend about whether they should change the name of the China dreamer awards. In the end, they decided not only to continue to call it the “China dreamer award,” but to publish a book celebrating the work of its winners: The China Dream: Stories of 38 Practitioners.9

Unfortunately, the Southern Weekend 2013 New Year’s editorial, “The China Dream, The Dream of Constitutionalism” did not fare so well. It was censored, and then rewritten by the provincial propaganda chief to endorse a national dream of strong state power.

But in another way it was quite effective; this censorship generated considerable protest from journalists in China. It then sparked a lively wider public debate about the rule of law in the PRC, which continued into 2014. Indeed, it likely provoked the Politburo to make the rule of law the topic of the 4th Plenum of the Central Committee in October 2014. This then is a prime example of what China dream discourse can “do”—it can set off debates in unpredictable directions. While not leading directly to political reform, this constitutional debate certainly made the party-state feel the need to publicly defend what it means by the rule of law and what it means by the China dream.

Joining the broad debate over the proper shape of the China dream, a political scientist in Beijing suggested that “as a political slogan the China dream should be inclusive. Only when everybody has their own personal dream will we be able to share some common elements.” Yet he worried that the way the slogan was being “propagandized” was “transforming it into a collective dream, a national dream, without much space left for individuals.” He felt that “we should give everyone enough space for their own individual dream, which may have nothing to do with the collective dream, because only when all these personal dreams come together can the collective dream develop.”

Some of Xi Jinping’s statements supported such a bottom-up interplay of individual, collective, and national dreams. When he introduced the concept of the China dream in November 2012, Xi actually recognized that “everyone has their own ideals and aspirations, and all have their own dream. Now, everyone is talking about the China Dream.” In his speech at the National People’s Congress in March 2013, Xi explained that the China Dream is “the people’s dream, and must closely rely on the people for its achievement, and must constantly be for benefit of the people.” He continued to explain, “the China Dream is a national dream, and is also the dream of every Chinese person.” Indeed, the second chapter of Xi Jinping’s book of quotations is entitled “In the Final Analysis, the China Dream is the People’s Dream.”

But the tension between the collective and the individual is not as flexible as it first appears. Official China dream discourse is better understood as the party-state’s reaction to bottom-up notions of the China dream as a collection of individual dreams. Indeed, before the China dream became an official discourse in November 2012, individual dreams were quite popular in public discussions of the PRC’s future direction.10 But at the “Road to Rejuvenation” exhibit, Xi stressed how the country and the nation have to come first: “History tells us, the destiny of each person is closely connected to the destiny of the country and of the nation. Only when the country does well, and the nation does well, can every person do well.” He later told a group of elite youth that they did not just have a “personal relation to the China Dream,” but had a “personal duty to completely achieve the China Dream.”

In other words, individual dreams are important, but only acceptable when they support the collective national dream.

The China dream thus is part of a national identity project. But what kind of identity is it promoting? Xi Jinping first discussed the China dream at the end of the Politburo Standing Committee’s tour of the “Road to Rejuvenation” exhibit at China’s National History museum, where he declared that he had “learned deep historical lessons.”

In Seeking Truth, a well-known official commentator asked “Why is the China Dream so hot? Why does it so move so many people? Why does it have a strong resonance?” His answer was “because the China Dream wakes up people’s deep historical memory.”11 History here is not merely China’s 5,000 years of glorious civilization, but also its 170 years of humiliation where “capitalist imperialist powers invaded and plundered China,” and imposed “humiliating unequal treaties” after the first Opium War with Britain 1840.12 It is noteworthy that Xi launched the China dream as his signature slogan at the “Road to Rejuvenation” exhibit because it is ground zero for China’s victimized sense of national identity as national humiliation.

Although the national humiliation historical narrative is presented as a “fact” in Chinese textbooks, it is better understood as the party-state’s response to the 1989 Tiananmen movement. A patriotic education policy was formulated in the early 1990s to shift the focus of youthful attention away from domestic issues and towards foreign problems. National humiliation themes thus are utilized in patriotic education not so much to re-educate the youth (as in the past), as to redirect protest toward the foreigner as the key enemy.

The optimism of the China dream here depends on the pessimism of the national humiliation nightmare. Xi thus rejuvenates not only the Chinese nation; China dream discourse also rejuvenates what can be called “pessoptimistic nationalism.”13 The China dream thus is not just a positive expression of national aspirations; at the same time, it is a negative remembrance that cultivates an anti-Western and an anti-Japanese form of Chinese identity. It fosters mistrust of the international system, and sees Western calls for deeper Chinese participation in multilateral institutions as a nefarious “trap” designed to stem China’s rise. The China dream thus is embedded in an aggressive form of nationalism that is deeply suspicious of the current international system.

The China Dream as a Martial Dream

According to many, Xi Jinping got the China Dream slogan from a popular book by Colonel Liu Mingfu, The China Dream: The Great Power Thinking and Strategic Positioning of China in the Post-American Era (2010).14 After Xi made the China dream his official slogan, Liu’s book was republished in a new 2013 edition, which was prominently displayed in the party cadres’ special bookcase at Beijing Book City.

Liu’s China dream is interesting because it anticipated Xi’s new foreign policy of complementing China’s economic engagement with enhanced military modernization. Liu explains that “in order to build a harmonious world, [China’s] competitive spirit must be strengthened.” China’s competitive spirit here has to be not just economic, but also militaristic: “To rejuvenate the Chinese nation, we need to rejuvenate China’s martial spirit.” Liu warns that being an economic superpower like Japan is insufficient; as a trading state, China risks being gobbled up like a “plump lamb” by stronger military powers. To be a strong nation, Liu argues, a wealthy country needs to convert its economic success into military power. Rather than follow Deng Xiaoping’s “peace and development” policy to beat swords into ploughshares, he tells us that China needs to “turn some ‘money bags’ into ‘ammunition belts’.”

In this way, Liu refocuses China’s ambitions from economic growth back to political-military power. Liu’s goal is to “sprint to the finish” to beat the United States, and become the world’s next superpower. In 2013, Liu reasserted these ideas and strategy in the revised edition of his book, as well as in an article for the PLA journal, Theoretical Studies in Military Political Work.15

Xi Jinping endorsed this version of the China dream numerous times. On his inspection tour of the Guangzhou military region in December 2012, Xi explained that his China dream includes “a strong nation dream, which for the military is a strong military dream. For us to realize the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, we must support the unity of a wealthy country and a strong military, strengthen national defense, and strengthen the army.” Xi told China’s astronauts that “the Space Dream is an important part of the dream of a strong nation,” and that “manned space flight shows the value of the China Path, the China Spirit, and the China Power,” all of which are important aspects of the China Dream. China as a maritime power is likewise envisioned as part of the China dream; a photograph from mid-2013 shows sailors lined up on the flight deck of China’s new aircraft carrier to spell out the words “China Dream, Strong Military Dream”16 (see Figure 4). Indeed, in September 2013 Beijing issued a set of four “China Dream” postage stamps that feature the PRC’s aircraft carrier, two spacecraft, and a submarine (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: “China Dream, Strong Military Dream” on Chinese aircraft carrier

Source: China Central Television

Figure 5: “China Dream: Wealthy and Strong Country” postage stamps

© William A. Callahan

The China dream here is part of the debate about the PRC’s “values crisis.” It provokes discussions of Chinese values that range from a broad aspiration for individual and national success, to a narrower victimized form of illiberal nationalism, and finally to a “strong nation” nationalism that promotes martial values. The contrast between the Voice of the China Dream TV show and “China Dream, Strong Military Dream” on China’s new aircraft carrier is indicative of the tensions involved in China dream discourse: the contestants on the Voice of the China Dream TV show are involved in pursuing dreams of individual fame and fortune, while the sailors lined up on China’s aircraft carrier are acting as a faceless group to pursue the collective dream of national strength.

Rather than accept that China is being socialized into the liberal international system, Xi’s China dream promotes two illiberal alternatives: socialism and Chinese civilization.

This comes out most directly when the China dream is discussed in relation to the American dream. Rather than being complementary visions of the future, the China dream is usually positioned as a challenge to the American dream. For example, just before Xi Jinping went to the United States to meet President Barak Obama in June 2013, the People’s Daily explained the “Seven Major Differences between the China Dream and the American Dream”17 in terms of China’s dream of national wealth and power, and Americans’ dreams of personal freedom and happiness. China here is defined as a nation united in its rightful pursuit of global power, while America is portrayed as a collection of individuals bent on their own selfish schemes.

Xi Jinping reinforced the cold war geopolitical sense of the China dream at the “Beijing Forum on Art and Literature” in October 2014 when he praised a young blogger, Zhou Xiaoping, for spreading “positive energy.” Zhou is most famous for his discussion of the China dream as a rich alternative to what he calls the “Broken American Dream.”18 The goal here is to convince people that Chinese values are not only different from American values, but are the opposite: Chinese values are good, while American values are evil.

What Can China Dream discourse “Do”?

If we move from the ideational to the material, we can see that Xi Jinping is using the China dream as a “broad church” composite ideology in order to build a coalition of competing interests in China. When we switch from the content of Xi’s speeches to examine their audiences, we can see which groups he is bringing together—and which he is leaving out.

Soon after Xi was chosen as the Secretary General of the CCP in November 2012, he made a series of high-profile speeches to promote his new priorities. As Xi’s book of collected quotations shows, he spoke in general terms to broad audiences: numerous communist party organizations (the Politburo, the Central Committee, the Central Party School, the Communist Youth League, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions, the All-China Women’s Federation, and so on), and to general national audiences (the National People’s Congress, the televised speech at the National History Museum, and so on).

Xi also spoke to quite specific audiences. On his first tour outside Beijing, Xi went to Shenzhen, the birthplace of China’s economic reforms in the early 1980s, to endorse greater economic reform as the correct path for China’s national rejuvenation. Xi spoke at various military bases, including the headquarters the Guangzhou military region, the Naval Base at Sanya, and the headquarters of China’s nuclear weapons arsenal, the Second Artillery Corps. Xi’s speeches also addressed the social and economic concerns of individual Chinese: he promised to benefit the common people (老百姓) by delivering a moderately prosperous society by 2020, and a prosperous, strong, democratic, civilized, and harmonious country by 2049. Lastly he spoke to elite groups of scientists and intellectuals (many of whom were trained in the West), to enjoin them to “harness the energy of their personal dreams to the task of realizing the China dream,” and thus use their expertise for the motherland.

Hence in his first year in office, Xi Jinping conducted a retrospective election campaign. In China’s one-party system, the heir-apparent is expected to silently support the current leader. Hence the campaign to excite the grassroots (i.e. party members) and cobble together a coalition (e.g. business, the military, and rank-and-file Chinese citizens) can only take place after the new leader has taken power.

The conflicting discourses of socialism and civilization here are not a contradiction; they are joined together through the China dream into a composite ideology that cobbles together different interest groups. Xi Jinping thus is promising both guns and butter, deeper marketization and the preservation of State-Owned Enterprises, and an orderly society that also has a measure of social and economic freedom. His “China dream” is for the PRC to be an authoritarian capitalist civilization-state that has international influence backed up by a strong military.

Xi Jinping’s China dream has coopted the language and arguments of many public intellectuals in the military and the New Left. China’s liberals, however, are largely excluded from this new coalition. Economic and social space is expanding in China—but political space, especially oppositional space, has narrowed considerably in Xi’s first two years as leader. Individual dreams of an economic and social “good life” are encouraged—but as we saw with the debate over constitutionalism, dreams of individual political rights and liberties that challenge the party-state are discouraged.

Hence to answer the question posed in this essay’s title: “What can the China dream ‘do’ in the PRC?” It is being used to form a coalition that sees the future of China in terms of an authoritarian capitalist civilization-state that is guided by martial values. The goal of China dream policy thus is not only to tell people what they can dream, but more importantly, what they cannot dream: individual dreams, democratic dreams, the constitutional dream, and the American dream.

1. Gloria Davies, Worrying about China: The Language of Chinese Critical Inquiry (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007); Liu, Zhongguo meng.

2. Xi Jinping in Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi, ed., Xi Jinping guanyu shixian Zhonghua minzu weida fuxing de Zhongguo meng: Lunshu gaobian [Xi Jinping on realizing the China dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation: Discussion edition], (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, December 2013), 3.

3. Zhonggong zhongyang xuanchuan bu lilun ju [Central Propaganda Department of the CCP, Theory Section], Zhongguo meng: Chanshi ‘Zhongguo meng’ wenzhang xuanbian [The China dream: Selected articles to explain ‘the China dream’], (Beijing: Xuexi chubanshe, 2013); Wang Yingmei and Wang Pujing, Zhongguo meng: Dangyuan ganbu duben [The China Dream: A reader for party members and cadres], (Beijing: Yanjiu chubanshe, 2013); Xu Hui, Zhongguo meng: Xuexi fudao baiwen [The China dream: 100 questions for study and guidance], (Beijing: Yanjiu chubanshe, 2013); Zhonggong zhongyang xuanchuan bu lilun ju [Central Propaganda Department of the CCP, Theory Section], Zhongguo meng, women de meng [The China dream is our dream], (Beijing: Xuexi chubanshe, 2013); Tuoqi Zhongguo meng [Uphold up the China dream], (Beijing: Xinhua chubanshe, 2013).

4. Frank N. Pieke, The Good Communist: Elite Training and State Building in Today’s China, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

5. Yan Xuetong in Bill Callahan, dir., “China Dream: The Debate,” January 2014, http://www.chinafile.com/library/books/China-Dreams.

6. See Ian Johnson, “Old Dream for a New China,” New York Review of Books blog, October 15, 2013.

7. Dai Zhiyong, “Nanfang zhoumou weifachu de xinnian xianci: Zhongguo meng, xianzhengmeng” [Southern Weekend’s Unpublished New Year Editorial: China Dream, the Dream of Constitutionalism], 2013. http://www.l99.com/EditText_view.action?textId=612255.

8. Lung Ying-tai. “Wenming de liliang: Cong ‘Xiangchou’ dao ‘Meilidao’” [The power of civility: From ‘Homesickness’ to ‘Formosa’]. Speech given at Peking University, August 1, 2010, http://blog.caijing.com.cn/expert_article-151497-9753.shtml.

9. Nanfang zhoumo, Zhongguo meng: 38 ge jianxingzhe de gushi [The China dream: Stories of 38 practitioners], Nanchang: Ershiyi shiji chubanshe, 2014.

10. See William A. Callahan, China Dreams: 20 Visions of the Future (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

11. Qiu Shi, “Zhongguo meng huiju pang bo zheng nengliang” [The China Dream brings together boundless positive energy], Qiushi no. 07, April 1, 2013.

12. Qiu, “Zhongguo meng.”

13. See William A. Callahan, China: The Pessoptimist Nation, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

14. Liu Mingfu, Zhongguo meng: hou Meiguo shidai de daguo siwei zhanlue dingwei [The China dream: The great power thinking and strategic positioning of China in the post-American era], (Beijing: Zhongguo youyi chuban gongsi, 2010).

15. Liu Mingfu, “‘Zhongguo meng’ yinling zhongguo qianjin,” [The ‘China dream’ will lead China forward], Jundui zhenggong lilun yanjiu 14:3 (June 2013): 135-38.

16. “Sailors of aircraft carrier Liaoning line up to form ‘Chinese Dream’ on deck,” China Central Television, http://english.cntv.cn/20131120/103819.shtml.

17. Shi Yuzhi, “Zhongguo meng qubie yu Meiguo meng de qi da tezheng” [Seven major differences between the China dream and the American dream], Renmin luntan, May 27, 2013, http://comments.caijing.com.cn/2013-05-27/112830491.html.

18. Zhou Xiaoping, “Meng sui Meilijian” [Broken American dream], Dangjianwang, September 13, 2013 [reposted September 19, 2014], http://dangjian.com/jrrd/wptx/201409/t20140919_2188807.shtml.

Rejoinder

It has been two years since Xi Jinping assumed the top position in China. He announced a catchy slogan “China Dream,” which has become a mantra in the official Chinese discourse. Where are things now? The New Year holiday is a good time to examine the Chinese political discourse because this is when the propaganda apparatus summarizes the party’s achievements in the past year and signals the tasks ahead.

If one picked up Renmin ribao on January 1, one would immediately see the prominence of Xi Jinping, as intended. Five news stories highlighted Xi’s remarks and diplomatic activities, taking up about six-sevenths of the front page. Xi did not mention the “China Dream” in his New Year Day’s speech, but used the term once in his New Year’s Eve remarks at a tea chat meeting for retired senior officials. As had become clear through 2014, Xi has developed a variety of slogans and initiated several major policy initiatives, all of which were covered. But if one wants to know the main task for the party for the year, one should pay attention to another front-page summary of Xi’s article on speeding up construction of a “socialist rule-by-law country.” The familiar “socialism with Chinese characteristics” theme was highlighted. The overall impression one gets from reading the Renmin ribao front page is that Xi is the Chinese leader bar none and he cares about people’s concerns, commits himself fully to the major domestic challenges, possesses a global sensibility, and faithfully walks down the socialist path.

As is often the case, a strong leader does not have to spout his own slogans, much since those under him amplify the leader’s vision. The “China Dream” remains a high-frequency theme throughout the Chinese political system. On January 5, 2015, Renmin ribao had a front-page summary of the ideological work done in the past year, which also anticipates what should be emphasized for 2015. The thrust in 2014 was described as making sure that the party and masses would have a strong ideological basis for a series of important reform measures launched during the year and rallying behind the party center under Xi’s leadership. This year will see a continuous campaign to publicize, educate, and research the “China Dream,” with also a focus on a global propaganda offensive to tell “China’s stories” and make “China’s voices” heard. The “China Dream” was termed the biggest and most splendid China story. The article put equal emphasis on “socialist core values,” giving some examples of what they might look like, allowing for more substantive discussion than the “China Dream,” which is only a slogan. Thus, if one writes about the Chinese political discourse at present, one is better off starting with the “socialist core values” idea, while touching upon the “China Dream” story.

The “China Dream” theme still helps us to understand some important aspects of Chinese politics and foreign policy. As an aspiration, it sheds light on the Chinese government’s intentions. In particular, Chinese propaganda exhibits a stronger tendency now to use the “China Dream” when discussing foreign policy. In that context, the use of the “China Dream” is consistent with China’s more assertive foreign policy. After all, the full name of the “China Dream” is “China’s dream for a great revival.” It is well understood in China that a great revival starts at home, but China is aspiring to return to its glorious days as the center of Asia, a mindset that continues to be a source of tension in the region.

Moreover, how different parts of the Chinese political system attach their organizational interests to the “China Dream” continues to be revealing. Just to relate to China’s greater assertiveness in foreign affairs, the PLA has linked the “China Dream” to a “strong army dream.” Not surprisingly, its main newspaper Jiefangjunbao focused on the strong army theme in its New Year Day’s editorial, even as that day’s front page was virtually identical to that of Renmin ribao. It carried verbatim the same five stories related to Xi. Other than the paper names, the only difference is in the bottom right corner. There, using a muscular and folksy writing style distinct from the party newspaper, Jiefangjunbao pledged loyalty to Xi, fully supporting his call for prioritizing preparation for “military struggle” and his campaign to rule out corruption within the armed forces. The editorial did not explicitly link the “China Dream” and the “strong army dream,” but that linkage has been well established and embraced by the army and many civilians. Different from the party paper, this paper’s editorial darkly warned against Western online programs for “cultural Cold War” and “political genetic engineering” to pull officers and soldiers from their political roots and snatch their souls in order to separate the PLA from the party leadership.

I look forward to reading William Callahan’s timely monthly analysis of the “China Dream” in the larger context of Chinese political discourse and policy initiatives.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn