With this first issue of The Asan Forum, we post our first Special Forum, five articles that address different aspects of a single overarching theme on Asian international relations. Each Special Forum will have an introduction, identifying common themes in the articles and pointing to some comparisons of their findings. Rather than five unrelated writings, we strive to achieve a multiplier effect through a coordinated approach to strategic thinking across the Asia-Pacific region, to the search for new frameworks for analyzing developments, and to divergent thinking on timely issues.

The prospect of another cold war, scarcely raised in the 1990s-2000s, has recently drawn increased attention. A few realists, under the spell of deductive logic or historical analogy, raised it earlier. Obsessed by the record of China’s Communist Party, a small number of China watchers made a rather seamless transfer from prior warnings against the Soviet threat to a China threat, especially after the June 4, 1989, intensification of oppressive measures. Yet, until recently, the prevailing outlook was liberal optimism about the predominant weight of a market economy—international economic integration—in soothing tensions among major powers in the Asia-Pacific.

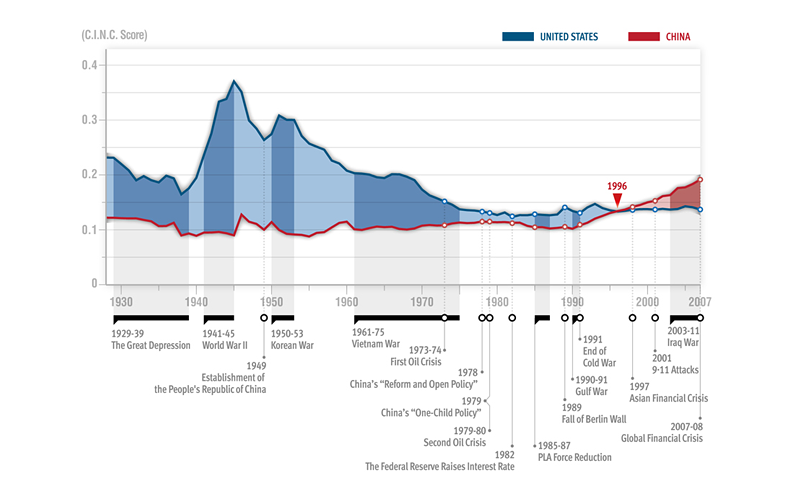

Why has the mood shifted? Multiple reasons are discussed in the articles that follow. Here I single out four. First, we observe China’s rapid emergence as a military great power along with unprecedented assertiveness in pressing territorial claims and charges against US containment. A second mood changer is the widening gap between China’s more confident identity as an alternative global model, parallel to reduced confidence in the United States, Japan, and EU states. Third, North Korea’s flaunting of nuclear weapons and missiles to a divided and inadequate international response has showcased a relic of the old Cold War and, indeed, its hot war flare-up. Finally, a further reminder is Russia’s renewed anti-Americanism coupled with a deepening “strategic partnership” with China. Most observers do not argue that these and other warning signs cross a threshold sufficient to be deemed harbingers of a new cold war, but the thought has recently been crossing many more minds. Cyberthreats are the latest hot button issue that is arousing strident warnings.

Our objective is to weigh the pros and cons on various dimensions of the case that another cold war is on the horizon. An essential first step is to define what is meant by cold war, avoiding the troubling outcome of differing conclusions premised on different definitions. If one were to define cold war strictly in accordance with the precedent of the bipolar struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States that would be a recipe for concluding that no repetition is in store. Although that precedent is all we have in establishing basic principles for what constitutes a cold war, and we need to start with it, we also need to show flexibility in separating some non-essential elements, as we consider differences that might not rule out another cold war appearing. The starting point is clarity on the minimal signs of a cold war.

For purposes of these articles, we start with the following five points as signs of a cold war. First, a cold war requires an arms race between the world’s two most powerful states with an uncertain outcome. Second, it necessitates that these states are mutually critical of each other’s ideology or national identity, competing for support elsewhere partly on the basis of denying the other’s moral authority. Third, a cold war involves power-balancing, strengthening and weakening alliances and regional organizations in a competitive, if not adversarial, atmosphere. Fourth, we leave open the degree of economic cooperation that exists, insisting only that there be clashing claims about whose model, including the role of the state, is superior. Finally, in a cold war the global spotlight shines on visits between the leaders of the two rival states, whether they raise hopes of detente and a positive shift in relations or arouse fears of a chill ahead. The Obama-Xi Sunnylands summit of June 7-8, 2009, drew the kind of rapt attention that would be expected from a meeting of this sort.

We asked each author to conclude, on the basis of the dimensions covered in his chapter, how likely it is that we are entering a Sino-US cold war. The instructions are to avoid a “brief,” making just the case pro or con. Instead, arguments on both sides should be weighed in the process of drawing an overall conclusion. The fact of our writing on this topic means that the prospect is, at least, being taken seriously.

One argument against the emergence of a new cold war is the assumption that China and Russia are committed to the development of multipolarity, as has often been stated in their joint statements since the mid-90s. Yet, this is outdated thinking. As Chinese writings as early as 2009-10 made clear and some Russian writings now acknowledge, bipolarity with China and Russia on the same side is growing more likely. This tendency is stronger in China. Claims that both states oppose joining any alliances increasingly ring hollow against recent calls for closer ties in the face of supposed US ambitions. Yet, as Stephen Blank argues, new arms sales by Russia to China and joint naval exercises at present fall short of a cold war threshold.

Reading Chinese and Russian sources on the struggle for a “new order” in East Asia, one finds much that is reminiscent of the Cold War era. There is much written on a weakened United States resorting more to force, struggling to retain its sphere of influence in East Asia, striving to contain China’s rise in the region, and pressing to strengthen the military alliance with Japan and to keep South Korea in its orbit from fear that progress in inter-Korean relations would reduce the US role in the region.

Whereas few Western writings suggest a cold war, these see it as now under way.1 Yet, as Zhu Feng makes clear, China, as well as Russia, has contending schools of thought, and the pendulum has not swung decisively to the side of “cold warriors.” He argues that China’s leadership is much less inclined this way than many authors.

Unlike the somber official exchanges of the Cold War, most recent discussions of conflicting viewpoints are replete with acknowledgments of ambivalence and even diversity of thinking on each side. Even in official positions in the Chinese hierarchy, Chinese readily confirm that what is written openly is a pale reflection of what is circulated internally, and, even that, does not well capture what is stated orally. The standard of objectivity remains a tool in the struggle against distorted reasoning. Russians have a less restrictive academic and publishing environment, but many also write differently for internal reports and orally take advantage of the standard of objectivity. As long as these conditions hold, it is unlikely that we will cross one of the thresholds of a cold war. This supports what Noah Feldman labels a “cool war,” explaining that it will be less dangerous than the Cold War due to interdependence, but will grow increasingly tense as China’s geopolitical goals clash with US ones and China stokes what I am calling a “national identity gap” to boost regime legitimacy.2

The cause of “cold war mentality,” if not a full-fledged cold war, is perceived in China and Russia as US “hegemonic” thinking to contain China and to keep Russia from reviving. Allegedly, Washington saw an opportunity to extend its “empire” in the 1990s, acting unilaterally and using force in the 2000s, and breaking the existing balance of power by pivoting back to Asia at the start of the 2010s. This reasoning is buttressed by complete dismissal of any US claims to idealism, humanitarian or not, and by interpretations of resistance to the US behavior, even from North Korea, as basically justified. At its core, this is an argument about US national identity, not a particular leader or political force, and the effort to impose Western civilization to the detriment of other civilizations, two of which China and Russia represent.

A briefing by Tom Donilon, US National Security Advisor, at the conclusion of the Obama-Xi summit on June 8 provides the latest update on prospects for a cold war. Explaining what is needed to prevent deterioration of relations into a “strategic rivalry,” he interprets China’s call for building a new model of relations between two great powers as a pathway to “healthy competition” based on certain principles. For North Korea, these are spelled out as agreeing to Six-Party Talks only if they are “authentic and credible,” preventing it from becoming a proliferator, a threat to the United States, and a force upending security in Northeast Asia. Denuclearization was in the forefront in Donilon’s comments on “quite a bit of alignment” over North Korea, but he warned of steps that the United States may take to defend itself and its allies while calling for enforcement of the Security Council resolutions to pressure the North and for making assistance in its economic development conditional on its abandonment of nuclear weapons.3 This has been the foremost test of cooperation essential for averting a cold war, and it remains the test highlighted on the US side.

For sustaining a stable security environment and regional order, Donilon was clear that this means continuation of US rebalancing, first by what is seen as successfully reinvigorating alliances and deepening relations with the two emerging powers of India and Indonesia, and second by working on a political architecture that makes the East Asian Summit the premier security institution in Asia. This puts the United States fully into the regional order, denying China a separate sphere, Donilon called too for de-escalation of the territorial dispute between China and Japan, managing it through diplomacy, not actions in the East China Sea. Thus, he sees duality, meeting obligations to US partners and constructively, but conditionally, pursuing relations with China, as other states also desire. Cybersecurity is high on the US economic agenda, a matter of protecting intellectual property rights, along with the Trans-Pacific Partnership targeted for completion without China even if making it transparent to China is seen as part of economic openness. Scott Harold’s chapter suggests that even on the economic dimension, signs of a possible cold war are not far below the horizon. Following Chinese writings closely, he sees danger signals.

None of the authors argues that a cold war exists or is imminent, but all of them point to features that bear resemblance to the Cold War. Even when they argue that a new cold war is unlikely, offering clear explanations why, some of their evidence is not obviously supportive of that conclusion. Rex Li’s discussion of national identity is focused on sharp differences, which could intensify, especially if three of the five schools identified by Zhu Feng establish ascendancy and also shape policy choices. Michishita Narushige and Peter van der Hoest take note of the current tense divide between China and Japan, which more than any other bilateral relationship has the potential to become a chasm. Yet, from the perspective of international relations theory, they are hesitant to conclude that we are entering a cold war. If no joint conclusion is possible, we should, at least, be stimulated to think more clearly and deeply about the divisions that exist in the region and how they may lead to a more lasting and irreversible bifurcation between a US-led order and a China-led order.

1. M.I. Krupianko and L.G. Areshidze, SShA i Vostochnaia Aziia: Bor’ba za novoi poriadok (Moscow: Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniia, 2010).

2. Noah Feldman, Cool War: The Future of Global Competition (New York: Random House, 2013).

3. “Press Briefing by National Security Advisor Tom Donilon,” GovNews, June 8, 2013, http://govne.ws/item/Press-Briefing-By-National-Security-Advisor-Tom-Donilon-1.

Print

Print Email

Email Share

Share Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter LinkedIn

LinkedIn