I have read with great interest all three pieces by Daniel Twining on “India’s New Leadership and East Asia.” These engage in a very timely debate and seem grounded in a balanced approach, calibrating clear coverage of issues and contentious perspectives. But beyond complimenting Dan for his lucid analysis, let me add a few divergent notes for his consideration and possibly elicit some responses.

First, his contributions are clearly located in the euphoria of unprecedented outcomes of India’s 16th general elections. For the first time since 1984, a single party gaining this kind of a clear majority and also defeating the Congress Party make these elections unprecedented. Daniel makes a convincing case of this change being deep-rooted, given that half of India is under 25 and two-thirds under 36 years of age. Also the fact that 551 million Indians actually voted in these elections makes it decisive. But foreign policy has rarely, at best only recently, been an issue in India’s elections. Second, this is one area which has enjoyed unusual consensus among all major political parties, barring fringe groups or views of fringe themes. Third, increasing federalization of Indian politics and three decades of coalition governments have made continuity, not change, the hallmark of India’s foreign policy. This inertia is not likely to shake loose easily.

Second, historically the foreign policy of the Congress governments have always focused far more on the global scene and given priority to great power relations—this explains Rajiv Gandhi’s path-breaking visit to rising China in December 1988—, but the Hindu nationalist parties have always focused on India’s immediate neighborhood, which is confirmed by Prime Minister Modi’s recent initiatives. Given the changes in India’s internal and external circumstances, this narrow focus may be expanded this time to the extended neighborhood but nothing more than this. Modi is not likely to stake his government’s survival on any possible deal with Washington. If anything, he could be more circumscribed by his party’s ideology and its circumstances. Even with China his focus will remain on building economic ties, pushing the border issue to the margins of their complicated relationship.

Third, I take note of a few specific issues that are difficult to get one’s teeth around, let alone digest and internalize. Some of these may be explained by the author, perhaps, being caught relatively off guard in his second and third pieces responding to rejoinders, and also by him trying to drive home his points without being understood so easily. These seem to push this article on “India’s New Leadership and East Asia” into narrow China-India polemics. For instance, the author uses expressions like a “simmering border dispute,” involving regular “skirmishes” on the China-India border, and “New Delhi’s strong support for Tibet,” and China granting stapled visas “to support the succession of Indian territory in Kashmir.” He even talks of India supporting the North Vietnamese in the 1960s and of India’s military alliance with Moscow in 1970. My personal favorite is the cliche of 800 million India’s living under USD 2 a day.

I briefly respond to these in reverse order. The last comment seems misplaced and clearly misses the logic of purchasing power parity. The almost decade-old nation-wide scheme under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act expects the Government of India to revise the minimum wage on an annual basis and the revised daily wage for 2013-2014 is USD 3.50. This scheme assures employment but only for seventy days a year. According to the recent order of the Government of the National Capital Region of New Delhi in April 2014, the minimum wage for unskilled wage labor is fixed at approximately USD 5. Surely, in a family (average of five members, i.e., one old person and two children), two adults being employed for all 365 days will mean USD 2 a day. Matters seem more complicated than can be explained by using binaries or cliches.

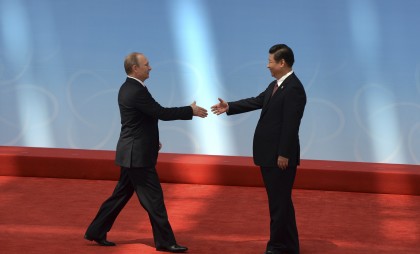

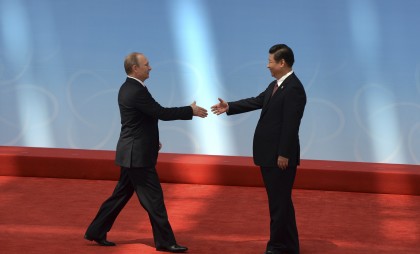

China does not issue stapled visas to all Indian citizens living in Kashmir valley, which is part of India’s Jammu and Kashmir province. Random sampling seems to be the only logic, which may be rarely calibrated. And this being China’s support for “territorial succession” seems like stretching it beyond belief. So is India’s support to Tibet, which ended in the mid-1970s, and even the Dalai Lama’s dialogue with China has been deadlocked since 2010. India’s treatment of Tibetans during the Chinese leaders’ visits would be a good barometer to judge this. “Simmering border dispute” and regular “skirmishes” seem equally misplaced. Even during the so-called eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation during April 2013, while retired generals and anchors on television were shouting for rolling out the tanks, political leaders were sanguine and soldiers on the border waving and smiling from both sides.

No doubt, there are rare incidents of misunderstanding on the line of actual control (LoAC), but these are always resolved without tempers rising high. The contrast with the line of control (LoC) with Pakistan makes it an especially glaring example of tranquillity. In brief, the border dispute between China and India has come to be nothing more than a medium of signalling displeasure. The China-India border issue will be resolved gradually into insignificance by the process of de-territorialization of national discourse. Even in the worst case scenario, both sides have shown that they have better ways to contest and undermine each other than falling prey to 20th century crude military strategies. India’s elections and the new leadership can at best decelerate or accelerate momentum on a few sub-themes, and they are not going to change India’s foreign policy in any substantial manner.